Table of Contents

“There’s something special about Japan,” intimated the old man, drawing my curiosity by letting the statement hang.

“I’d like to know about that.” I eventually prompted after an extended pause, leaning in.

“Well, you see, Japan has four seasons.” And with that, he sat back.

The more conversations you have in Japan about the nation and its culture, particularly with older generations, the closer to certain it becomes that you will be informed, occasionally with some gravity, that Japan has four seasons. Stay in the country long enough, and you may lose count of how many times this insight is offered.

Without meaning to be disrespectful though, it was an observation that left me, initially, underwhelmed.

So does England, I’d reflect.

And anyway, Japan doesn’t have four seasons.

This last argument was a little pedantic, but it struck me that some of my Japanese friends were hung up on Japan’s four seasons, despite there also being a distinct and frequently spoken about fifth mini-season called tsuyu, which means the rainy season, and which comes around with regularity every year.

Caught in the Rain

The land masses of Japan create a stretched-out, narrow archipelago, carving over 3,000 km through the Pacific Ocean from the country’s northern tip, which is close to Vladivostok, to its southern islands, which are not far from the coast of Taiwan. As such, the timing varies depending on where you live, but the seasonal rain front rolls up the country from south to north, and usually hits Tokyo (where I spent most of my time) around the beginning of June.

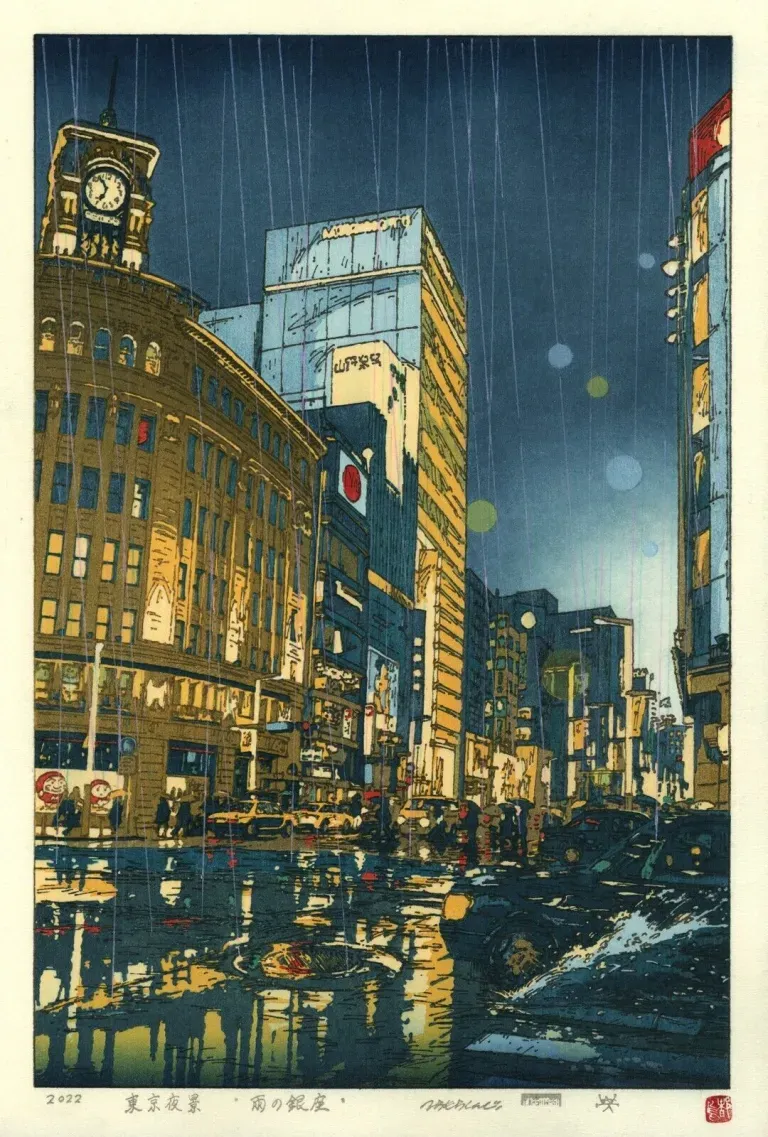

Although it varies in intensity from year to year, the rainy season would usually last five or six weeks, marking an interval between spring and summer. Rainy season is muggy and the air hangs heavy, sticking a little to your skin. It’s not blazingly hot and humid like the summer, but the vital freshness of the spring months is abruptly smothered. Sometimes you can perceive ominous shifts in the air pressure, the skies take on varying shades of gray, tipping occasionally into softly stormy near-blackness, and, of course, it rains.

Often there’s a fine mist, at other times it’s a more substantial drizzle, while at fiercer moments lashing sheets of water whip the pavements. Most likely, a few days will bring rumbles of thunder, but the wetness all around is warm and enveloping, and makes you feel far away from northern Europe and its chilly downpours.

Almost everyone I knew disliked and complained about the rainy season, for relatable reasons. You have to carry an umbrella all the time, you can’t hang your washing outside to dry, mold becomes a problem in closets at home, and you might not see sunshine for days on end.

As it goes, though, and not to be overly contrarian, the rainy season can be a uniquely enticing time of year. In a very intense rainy season, every day is dramatic, the atmosphere feels compressed and pushes in on you, and a darkly cinematic aesthetic shrouds the landscape.

In an always-on metropolis like Tokyo, such weather can make for some impressive views, as vapor coils round sky-high concrete and glass, and when daylight ebbs away, the bright lights of the urban environment flash and penetrate colorfully through sometimes dense condensation, creating neon mist and a dreamlike electric vista that wraps around you as you navigate its streets.

Alternatively, you might make your way to Japan’s more rural locations at this time of year, which can be equally thrilling but in different ways. On the Izu Peninsula, no more than a couple of hours drive from Tokyo, hiking routes take you through lush vegetation that grows greener with the storms. Some trails will throw you out onto rugged coastal paths, or reveal shrines and temples which are sometimes spooky, but at other times emanate sanctuary, depending on how the light happens to have fallen at that hour, on that day, through the trees and the rain.

When the time and the place are just right, then getting caught in the Japanese rain feels mesmeric, or even mystical, and you might just find yourself wishing to be caught again, and again.

72 Seasons

At first I reckoned, contrary to what I’d been repeatedly told, that there were not four seasons in Japan, there were five, or at least four and a half. Later, though, I discovered that my calculation had not gone far enough in adding to the traditional quartet. In fact, neither four nor five were even close to an accurate description, as it turned out that Japan has 72 seasons.

As unlikely as that at first sounds, it comes from an ancient system that originated in China, and which divides the year first into 24 major sections, which are all then subdivided into a further three parts each, giving a total of 72 micro-seasons, each of which lasts for around five days.

These precise segments are defined by and correspond with the conditions of nature throughout the year, but as the format originated in China, it didn’t initially match up accurately with the Japanese environment, and so in 1685, this detailed seasonal map was reconfigured by an imperial court astronomer named Shibukawa Shinkai.

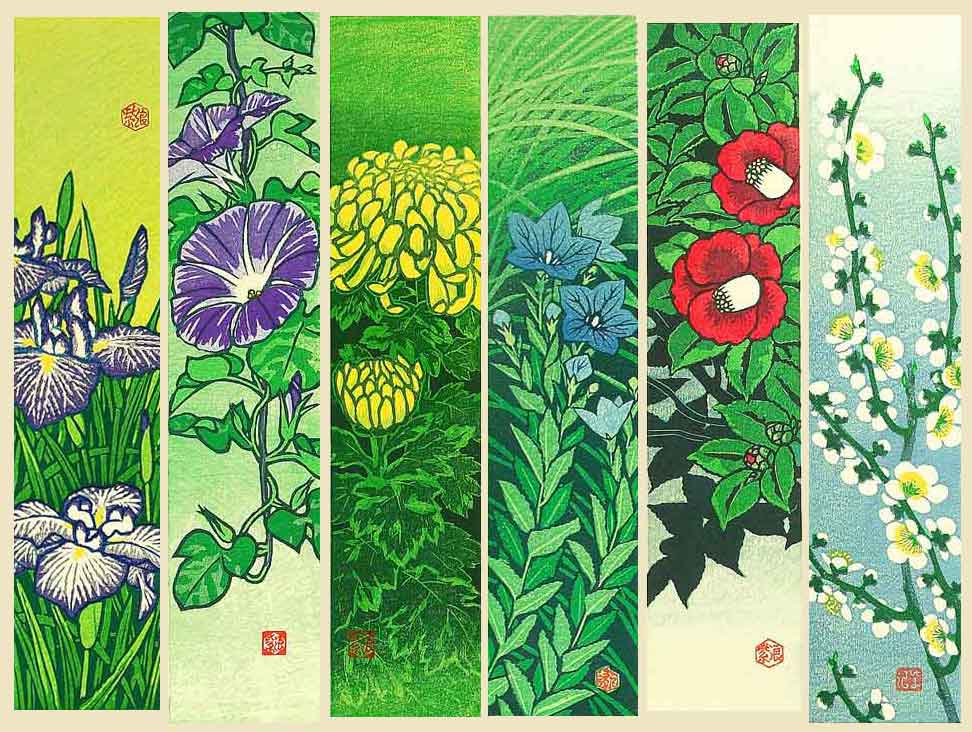

Coupled with exact dates, the micro-seasons are defined by evocatively descriptive guidelines, such as spring wind melts the ice, wild geese fly home, silkworms start feasting on mulberry leaves, and dew glistens white on grass.

Nowadays, the scheme seems a little out of sync again, and the natural changes it describes have themselves changed. I’m not sure who Japan’s court astronomer might be at the moment, but the 72-season calendar is an elegant marker of time that would merit a revival, perhaps in an updated format to match current cycles and modern observations.

One of the most appealing aspects of this system is that it links up directly with the sensory signals broadcast by the natural world, and it’s grounded in day-to-day, practical perception. On top of that, if there’s a season you can’t stand but have no choice other than to endure, then this calendar will break it down into manageable chunks and help you power through, a benefit that’s particularly useful in a country of seasonal extremes.

Freeze Until You Melt

After a while, I came to understand the real meaning underlying the declaration I kept finding myself on the receiving end of (while either nodding politely or making the case for tsuyu), that Japan has four seasons.

Sure, of course other countries, including rainy old England, go through a recognizably similar sequence of changes every year, but it became apparent that there are a couple of differences in Japan.

Firstly, the Japanese seasons seem to operate like clockwork, and are incredibly distinct from one another. It’s rare that you ever find yourself wondering whether the season has fully transitioned from one to the next, rather, it’s more as though you wake up one morning and someone flicked a switch, from winter to spring, for example (or wherever you might be in the calendar), and whoever is operating the machine tends always to execute the shifts at exactly the right time.

Secondly, in summer and winter the weather is intense, and so conditions swing, over the course of four, five or 72 seasons, from one opposite extreme to the other, with a couple of clement interludes on the way across.

If you’re in Tokyo, then you’ll be dripping wet with your own sweat throughout the sub-tropical summer, when the air feels like thick soup, monstrous cockroaches scuttle in the darkness of the sweetly stifling night, and you duck into convenience stores in the afternoons for a blast from the icy cold air conditioner that wakes up overheated customers at the entrance.

By winter, you’ll be back at the convenience store again, but now it’s to pick up hot canned coffee and disposable heated packs that can be shoved into gloves and boots, to keep you functioning as you trudge across the icy urban freeze. Snow dumps are short-lived in the capital, but the humidity levels drop to such an extent that, having spent the summer saturated, your skin is now desiccated and cracks apart at random moments, sometimes audibly. Moist as a vacuum-packed cornflake, you receive a static shock every time you touch a car door.

In spring and autumn the payoff arrives, and you can relax and gratefully bathe in delicately cherry-splashed hanami celebrations, or beside golden-leaved trees while the slow-baked heat of summer subsides, leaving you washed up and unraveled on a bleached beach somewhere in Shonan, and unable to recall, for a moment, which of those 72 finely-chopped seasons was supposed to be coming up next.

In the end, though, it’s unmistakable that each of Japan’s four major seasons is so distinct from the others that experiencing them all, simply by remaining motionless and letting time pass, is like taking a tour around four contrasting regions, each with their own colors and customs.

Hanami

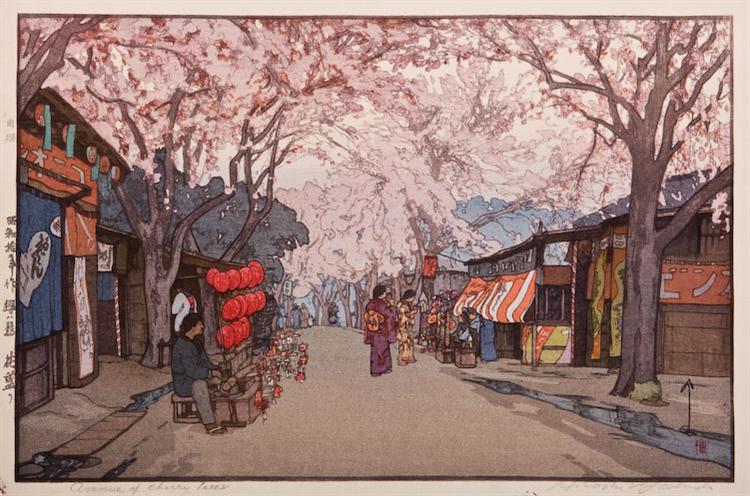

Of all the seasonal shifts and their corresponding activities, it’s cherry blossom time that receives the most attention, has become a symbol of Japan, and causes the most palpable sense of excitement.

It’s true that new year celebrations have a more official kind of importance attached: the country closes down for a few days (although more so in the past than now, as growing numbers of shops are remaining open), and most people travel home to be with family over new year holidays that are marked, in public at least, with quiet solemnity.

Cherry blossom season, on the other hand, does not contain any public holidays (the timing depends on the trees, after all), and business continues as usual. However, it’s the most expressively celebratory time of year, when the entire country seems to become overwhelmingly giddy and optimistic amid an explosion of pink and white.

Like the rainy season, but earlier in the year, the cherry trees reveal their blossom in a moving wave that sweeps up the country. Timings vary depending on the weather, but in Tokyo, the bloom usually opens at or around the beginning of April.

This synchronizes with the start of the Japanese academic year, and with the corporate calendar, by which new intakes of employees, freshly graduated from college and university, are recruited en masse. During April, then, it’s all-change and open horizons for many young people, and other workplace alterations tend to be scheduled for this season.

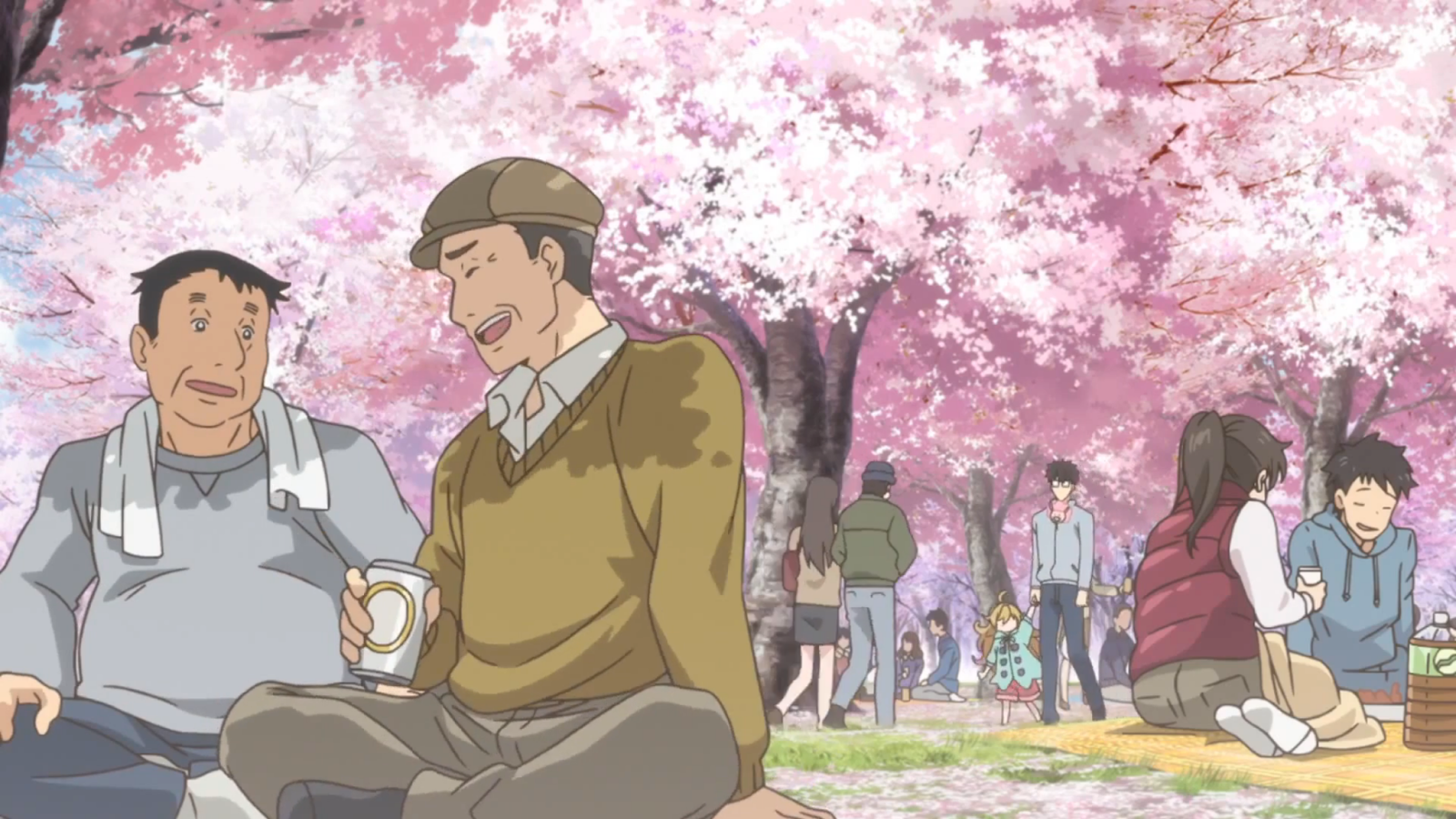

Amid new starts and spring air from which the winter chill has finally started to ease, is when the cherry blossom opens, and it becomes time to organize your hanami activities. Hanami means flower viewing–hana (?) is flower, and mi (?) is to look–and what that very often equates to, in contrast to the perceptions of strict social etiquette usually associated with Japan, are get-togethers in the park, a lot of alcohol, and a relieved clocking out from inhibitions and obligation.

It’s a joyous period, defined in part by its brevity, as the blossom won’t usually hang on for more than a week or so. There is an official announcement when the first buds open in the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine, which is located in Tokyo’s Chiyoda district, a center of imperial and political power, and national news will report on the percentage degree to which blossoms are open around the country.

In the parks, blue plastic mats are laid out on the grass, and parties of drinkers are then laid out on the mats, reaching various degrees of blurred raggedness as the afternoons slip into twilight.

In a rare case of Japan not being entirely in harmony with the natural surroundings, the blue mats are reminiscent of the kind of utilitarian sheets you might find on a construction site, and, in my humble gaijin opinion, blankets would be a more sympathetic choice, but this is a minor criticism.

Some areas are famous for their hanami events, while in others you can avoid the crowds, and the atmosphere varies from place to place.

For an authentic experience, there is Ueno Park. This expansive space is located on the east side of Tokyo, the older edge of the city that dates back to when the capital had a different name, Edo, and which retains a robustly old-time, no-nonsense spirit. By contrast, over in Kichijoji, a stylish but welcoming neighborhood towards the western edge of the capital, there is Inokashira Park, which attracts a younger hanami crowd, but becomes formidably packed, as do the bar-and-restaurant-lined streets nearby.

If you want somewhere in the center of the city but quiet and reflectively tranquil, then, as long as you’re not scared of ghosts, try walking through Aoyama Cemetery. You can unhurriedly breathe in the cherry blossom air and religious ambience, while orienting yourself towards Roppongi’s ever-blinking skyscrapers in the near-distance, among which, when you arrive, you’ll find yourself back among the crowds in Tokyo’s most international nightlife spot.

Traverse this route right at the end of the cherry blossom period, when the falling petals swirl thickly around you in an eddying breeze, and the experience will stay with you. There’s a special phrase for this brief window when petals fill the air, hanafubuki. As we saw, hana (?) means flower, while fubuki (??) is a snow storm, but we can translate it all as cherry blossom blizzard.

Limited Edition Days

It’s noticeable that when Tokyoites change their wardrobe for a new season, there are no half measures. Just as the seasons seem to switch as if mechanically, so a seasonal change of fashion is executed decisively, and is followed by other lifestyle alterations.

Food menus change, color palettes around shops and displays are altered, and daily life is recalibrated for the time of year. It’s popular among Japanese food and drink manufacturers to release limited edition seasonal variations, and this is especially apparent among breweries, including leading beer manufacturers such as Asahi, Kirin, Suntory, and Sapporo.

In early spring, or just before, the beer cabinet in every convenience store and supermarket is suddenly stocked full of sakura-pink cans, as the big names launch their annual hanami specials. Later in the year, the summer editions arrive, then in autumn, the cans turn auburn with the leaves, and at the end of the year, a winter aesthetic takes over.

I have yet to see a rainy season special, but I’m almost certain that tsuyu beer would fly off the shelves if any of the leading brewers were to put it to the test.

These temporary tweaks might come across as superficial, as while some seasonal beer editions use unique recipes, others are only really changing their packaging, and either way, alterations to the flavor are usually subtle and not nearly as apparent as changes to the can design.

However, it’s ostensibly surface-level changes like these that can, in aggregate, have a tangible effect.

The sense that’s created, and that it’s easy to get washed along with, is that the new, incoming season–whichever one it might be–is an event to be celebrated. After all, if it’s worth painting Asahi cans pink for, it must be something to look forward to, right?

I should stress that this goes beyond just corporate strategies by big-name brands, who are actually only tapping into the already existing sentiment around seasonal changes.

There is, in Japan, an approach to the passing years in which naturally cyclical changes in nature are focused on intently. Such celebrations come loaded with meaning for those who want it, most especially during hanami, which draws explicitly on the idea – Japanese cliche alert – of transience, and contains a bittersweet recognition that the seasons with which we’ve all been personally allocated are themselves limited editions, just like our cherry blossom beer, and should be consciously drunk in and tasted, and acknowledged, before they fall away forever.

Or at least, that’s what some people say, while others simply take in the view and lie back, can in hand. But then, perhaps lying back, can in hand, is exactly what an appreciation of transience should look like, so please, pass me an Asahi while the day is still warm.