Table of Contents

Lindsay Mitchell

Lindsay Mitchell has been researching and commenting on welfare since 2001. Many of her articles have been published in mainstream media and she has appeared on radio, tv and before select committees discussing issues relating to welfare. Lindsay is also an artist who works under commission and exhibits at Wellington, New Zealand, galleries.

The Child Poverty Report 2024 has just been published. It’s an overview and selected findings, as opposed to a full report which is due in 2025.

Poverty can be measured in various ways.

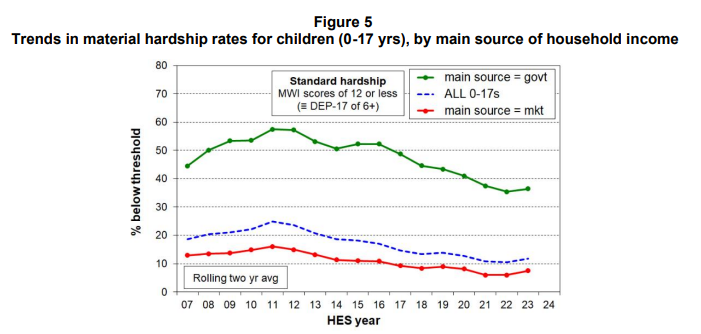

Material hardship is measured by asking survey questions about deprivation. Has a child gone without fresh fruit and veges, been subject to postponed doctor visits, experienced a cold and damp house, etc. The DEP-17 scale has 17 items and experience of 6+ is considered material hardship; 9 or more, severe hardship.

The following graph shows that children in beneficiary households experience material hardship at rates that are consistently, “four to five times the rates for children in working households”:

While the fall in the hardship rate is good news, the percentage of all children living in beneficiary families increased from 15 to 19 per cent between 2017 and 2024 (see Table 6).

So the rate of hardship has fallen but there are more children subject to it.

In my opinion, the growth in benefit-dependent children is primarily the result of increasing benefit payments and incentivising more families to opt for welfare and stay on it for longer.

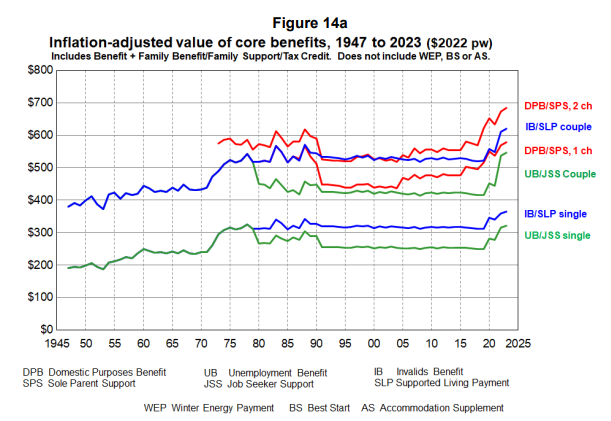

The following further graph from the report illustrates the steep rise in beneficiary incomes over recent years (but does not include Best Start, Winter Energy Payment or Accommodation Supplement.) A sole parent with two children receives just under $700 weekly. Adding in the exclusions however, pushes that figure up to $1,057 weekly (April 2023). See Page 6, https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/benefit-system/total-incomes-annual-report-2023.pdf

In respect of children in workless households, in 2022 (latest data) New Zealand was second only to Romania when compared to 26 European countries.

By family type the highest material hardship rate occurs in sole parent families at 32 per cent (compared to 12 per cent overall.)

The report notes, “New Zealand also has a relatively high proportion of sole parent households compared with European countries.”

Most children on benefits are in sole parent households (70 per cent).

In conclusion, the report shows that in general child well-being has improved and poverty has fallen.

However, the part of the equation that relates to those children living on benefits is not sustainable policy.

The numbers cannot be encouraged to keep growing. That will only ramp-up inter-generational dependency and further deplete potential productivity.

The feasible approach is that which Clark and Cullen adopted during the 2000s (but Ardern and Robertson shunned more latterly).

That was, work is the best way out of poverty. Always has been and always will be.

Simply shoveling ever more money into perpetually unemployed households is just another moribund idea from the Ardern era.

This article was originally published here.