Cranmer

Lawyer with over 25 years experience in some of the world’s biggest law firms. I divide my time between the UK and NZ. This Substack explores issues facing NZ at present under my nom du plume, Cranmer.

Last Saturday, King Charles III was crowned in London in a magnificent ceremony steeped in tradition that celebrated the continuation of the monarchy’s long history. Every detail emphasised its ancient past and the link between God, king, and country. More than that, it was a celebration of Britishness complete with pomp, pageantry and wacky eccentricity.

In the Commonwealth Realms, King Charles’ accession to the throne has been greeted in a more subdued fashion. Over many years, there was the suggestion that the Queen’s death would trigger reform of New Zealand’s constitutional arrangements. However, whilst questions of republicanism have inevitably arisen over the last six months, it is notable that both upon Charles’ accession to the throne and his Coronation, the discussion around those questions by politicians and in the media has been muted.

In his final press conference before departing New Zealand for London last week, Prime Minister Hipkins suggested that he was a republican because his belief was that in time we would become a “fully independent country”.

By the time Hipkins arrived in London his position had softened somewhat. In an interview with the BBC’s flagship Sunday television program hosted by the BBC’s political editor, Laura Kuenssberg, Hipkins described himself as a “technical republican”. Again articulating his belief that New Zealand would become a republic in his lifetime, he explained the country’s current reluctance for change was best characterised by the phrase, “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it”.

His principal objection as explained to Kuenssberg was, “If I was designing a system this wouldn’t be the system that I would design, but I also don’t think it’s a pressing issue. There’s a lot happening and this wouldn’t be at the top of the list.”

Based on the experience of the last six years, many New Zealanders will be thankful that Hipkins is not responsible for designing a new constitutional settlement for the country. But, in part, that is the point. The British constitutional monarchy is not a system that someone would design from scratch. It has been forged through 1000 years of glory, war and sorrow.

In its current form it can appear eccentric, stuffy and out-of-touch. But above all else it provides stability, continuity with the past and an embodiment of the nation. In its modern form, it encapsulates the apogée of soft power and diplomacy.

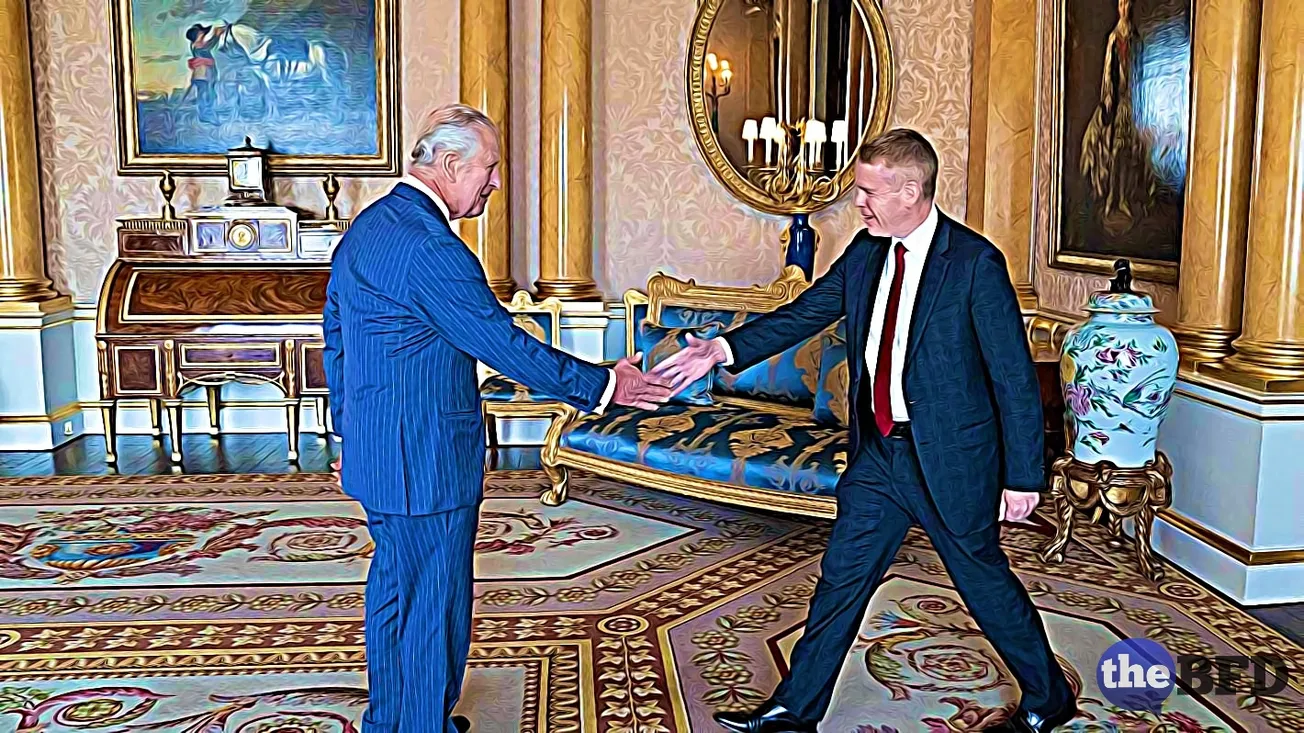

Even the republican Hipkins was charmed by the palace diplomacy last week, describing his meeting with King Charles at Buckingham Palace as “quite an amazing moment.”

“I remember, and I relayed this to him … as a very young New Zealander him visiting New Zealand in the 1980s and sort of lining up along the side of the road to wave at the then Prince of Wales as he was visiting.”

Later, Hipkins described the atmosphere within Westminster Abbey for King Charles’ Coronation as “quite phenomenal”.

In part, what Hipkins was articulating was his own personal connection with the monarchy. The majority of New Zealanders, like Hipkins, have ancestral connections to the United Kingdom and will have family members who have fought in the British Armed Services or alongside them in New Zealand Regiments. Many Kiwis have close family connections to the UK and have enjoyed living or visiting there themselves.

The monarchy provides a cultural connection to, for many, their motherland, and a link to our history as a young country. However, Hipkins mistakes the desire to become a republic as a sign of cutting the apron strings and a necessary step in the maturing of New Zealand.

To the contrary, our close links to the United Kingdom, and in particular, the role of King Charles as our Head of State, enhances our status on the world stage and provides us with a much needed bridgehead in the northern hemisphere. As world geopolitics becomes more complicated, and New Zealand and Australia acknowledge that the Pacific has become a “contested” space, it would be madness to jettison our oldest ally.

Many New Zealanders who support the monarchy feel that the status quo is not sustainable in the long term due to progressive arguments such as the ‘legacy of colonialism’ and the pressure that would arise if Canada or Australia were to become republics. However, there are two arguments that weigh against this happening, at least in the medium term.

The first is that the British monarchy is under huge pressure at home to modernize. While Queen Elizabeth’s reign will be forever celebrated, the institution will undoubtedly become slimmer and more nimble within a short period of time. Charles will likely govern in consultation with William and act as a bridge between his mother’s and son’s reigns, which will offer a measure of stability during a time of significant reform and which will help expedite the changes that William wants to see occur.

The second is that even if the legal changes are technically straightforward, New Zealand becoming a republic would unlock Treaty politics that will be very difficult to manage and which could prove to be highly divisive. It is a point which Bryce Edwards covers in his article, Why New Zealand’s Shift to a Republic Will Be Thwarted.

Co-governance, in all its different forms, has already been a contentious area for this current government. Whether it works in the management of natural resources, or in the delivery of national services, is an open question. Quite apart from the questions of practicality are the more thorny questions regarding its anti-democratic nature. Public disquiet about co-governance undoubtedly contributed to Ardern’s resignation and has been a significant drag on the government’s polling, leading Hipkins to pull back on the reforms.

Although the national debate on co-governance has focused on the Three Waters reforms over the last two years, in reality, co-governance is being implemented across the public sector and elsewhere at a scale that will surprise the public. Undoubtedly, Treaty politics will occupy a significant amount of the next government’s time whatever its stripes.

This means that until the heat is taken out of Treaty politics and the issue of co-governance is resolved, there doesn’t seem to be much opportunity for any government to address the republican question without seriously derailing its domestic agenda. At that point, the monarchy will, in all likelihood, look very different from how it looks now. The question then will be whether it can still act as the keystone that provides stability to New Zealand’s constitutional framework.