Table of Contents

By Raymond F Peters

Patriot Realm

In 1942, my wife’s uncle was a metallurgist in Papua New Guinea. At the height of WW2, he made do and mended in the jungles of one of the hotbeds of the conflict. Unable to serve in the war due to being deaf ( years of working in a goldmine in New Zealand), he served in his own way by doing his bit and carrying on.

Yesterday I found a transcript of his recollections of the time in Papua New Guinea during the war, and I wanted to share it with you. It is typed as he shared it all those years ago. His time in the war in the jungle of Papua New Guinea. As a courtesy, I have omitted parts that could identify him or his family. Here is his story of walking out of the jungles of PNG in 1942.

“ I was the Mill Manager of the X Mill and responsible for the smelting of all gold produced in the area. The women and children were being evacuated and we carried on running the works. When the Japs bombed Bulolo and Salomoa during January ’42, orders were given to close down the works and evacuate the area. One plane came in from Moresby and the older and sick men were taken out first.

We were waiting at the ‘drome one morning; the plane came in and was getting ready to load. An air raid warning went off and Jap planes could be seen coming from over the hills from the coast. The pilot took off, and, keeping low, went off to Moresby. We at the ‘drome scattered – the majority went to the creek to hide. I went back to the dry water race and kept my head down as the bombs started to fall. Some landed in the ‘drome and a few buildings were hit – a large number of bombs landed in the area where the men had hid. Several suffered broken bones but none were killed. Though I was 50 yards away, all I did was stop a lump of dirt and grass with my back.

The pilot came back in a day or two and started taking the older ones out again. He only made a few trips before he crashed in Cairns, I think it was, when taking off for another trip. He was killed. We were then told to walk to the south coast as it was considered safer than Wau, where we were.

We travelled by lorry to the start of the track to the coast. The track had no name at the time we walked it as far as I know. We carried bedrolls and a few things we could fit in a backpack. We had a few native boys to carry the food which was mainly rice. A bit of meat, bread and biscuits for a few days. But we ate mostly rice.

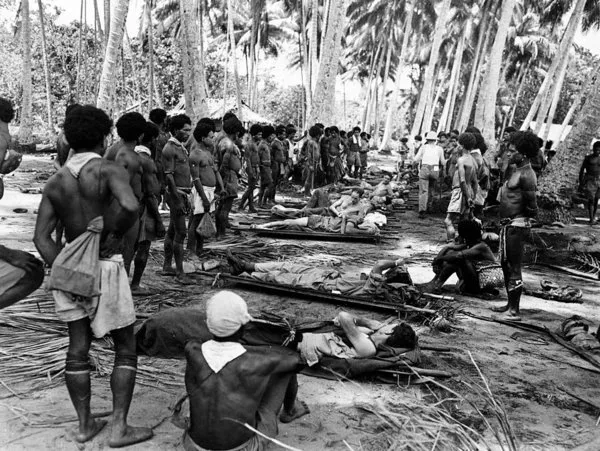

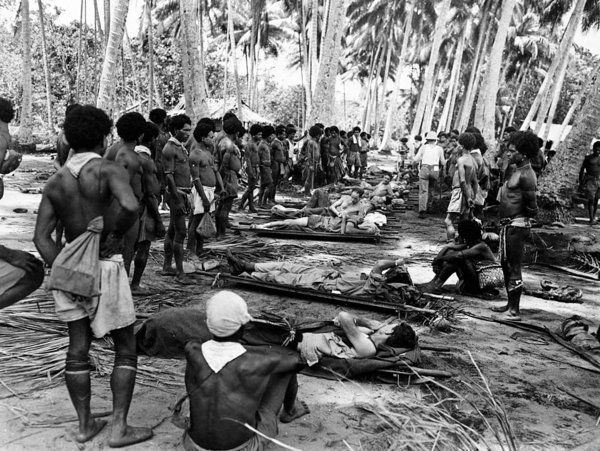

We would start walking about 8 am and might have a spell at midday, finishing about 4 pm. It was not particularly hot as the ridge we had to climb was 2000 to 3000 feet above sea level but some of the ridges we had to climb were rather steep. We had to hold on to trees and scrub to help us walk up the slopes. Mosquitoes were bad. Malaria was a risk because of the mossies. Lean to shelters were built from branches of trees and roofed with palm leaves on a floor of saplings. They were normally beside a creek and we would sit down for a meal of rice. The going was anything but level. We climbed up and up and down all day so we always slept pretty well at night.

We could see the Aussie planes flying over to attack the Japs – the natives were a bit scared of the planes so I explained to them that they were not “ Japan man “ planes but Aussies. I only met one native man with a child on our walk. We were not far from the coast and he couldn’t speak pidgin but, with sign language, he explained that the planes were flying all over and that we were not too far from our destination.

After about 10 days, we reached the mission station at Lakikama River. From there, we went by native canoes to the coast and boarded a lugger to Yule Island mission station. A day or two there and then another lugger to Port Moresby. We just got to the wharf when the air raid warning went off. Many jumped for the wharf. I noticed that the skipper had re started the engines and I decided to stay on board. As it happened, no bombs were dropped on the town. We were collected after the raid and driven to an army camp on the Lolakie river. After a few days, we were shipped out by boat to Townsville.

I tried to sign up, again, but was rejected for NCUR and NZ forces. I had a dose or two of malaria and had an attack of rheumatic fever but not that bad really. Apparently my heart had been affected so I couldn’t serve because of that, and of course, my deafness.

I was one of the first groups to walk out, but many in other groups were in their 70’s. We were lucky that we didn’t get too much rain on our walk.

Salamoa was destroyed by the Japanese bombing and was never rebuilt.”

My uncle went on to become a metallurgist in Mount Isa in Central Queensland. He died a bachelor and was well known for his thrift of penny and word. I always wondered why he was such a miserly old soul but this tale may give me pause to reflect on his penny pinching and reclusive ways. Maybe he appreciated the value of a bowl of rice and a rough shelter in the jungle; maybe he resented that his health disallowed him from serving his nation. Maybe his understated story of his walk left him a changed man.

When he died, back in 2000, he left, in his will, his not insubstantial fortune to his siblings and nephews and nieces. We benefited from this and were able to augment our modest retirement fund due to his generosity. We never squandered a penny from his legacy. And neither should we. After all, a man who survived on rice and learned the value of simplicity in order to stay alive deserved our respect and honour in his benevolence.

He made do and mended as so many did back then.

No cafes and smashed avocado in the jungles of Papua New Guinea.