Table of Contents

Roberto Musotto

Edith Cowan University

David S. Wall

University of Leeds

New research is questioning the popular notion that cybercriminals can make millions of dollars from the comfort of home — and without much effort.

Our paper, published in the journal Trends in Organised Crime, suggests offenders who illegally sell cybercrime tools to other groups aren’t promised automatic success.

Indeed, the “crimeware-as-a-service” market is a highly competitive one. To succeed, providers have to work hard to attract clients and build up their criminal business.

They must combine their skills and employ business acumen to attract (and profit from) other cybercriminals wanting their “services”. And the tactics they use more closely resemble a business practice playbook than a classic Mafia operation.

The Online Trade of DDoS Stressers

Using social network analysis, we studied crimeware-as-a-service payment patterns online.

Specifically, we looked at a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) stresser. A “DDoS stresser”, also called an IP booter, is an online tool that offenders can rent to launch DDoS attacks against websites.

In such attacks, the targeted website is bombarded with numerous log-on attempts all at once. This clogs up the site’s traffic and leads to all users being denied access, effectively causing the site to crash.

Buy Your VIP Cybercrime Membership Today

The stresser we analysed was taken down by Dutch law enforcement after six months of operation. Since all the identities involved were anonymised, we’ve called it StressSquadZ.

We explored StressSquadZ’s service operations and payment systems to observe how its service provider interacted with customers. Contrary to the idea of organised cybercrime looking like a cyberpunk version of The Godfather, their strategies seemed to come straight from a business playbook.

StressSquadZ’s provider offered clients a range of marketing and subscription plans. These started at an introductory trial price of US$1.99 for ten minutes of limited service, through to pricier options. Clients wanting a “full power” attack could buy a VIP bespoke service for US$250.

Clearly, StressSquadZ’s provider had a hankering to maximise profit. And just as we all appreciate a good bargain, their customers aimed to pay as little as possible.

(Cyber)Crime Doesn’t Always Pay

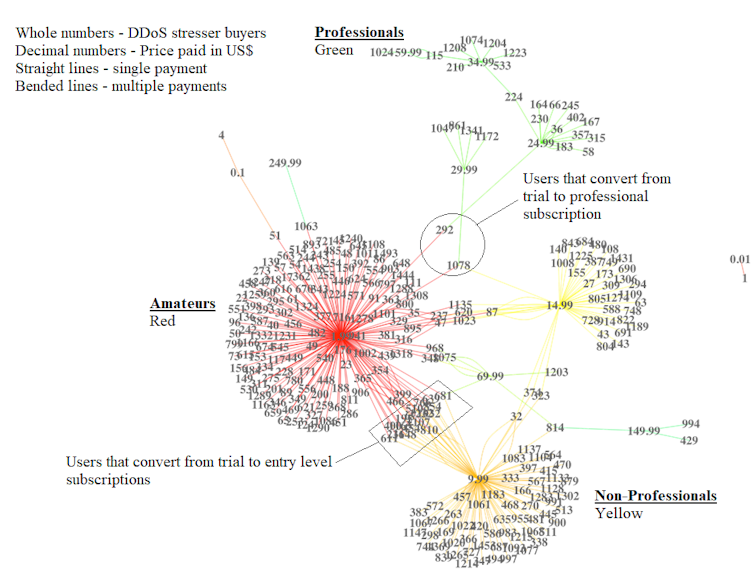

The communication data we analysed, mapped below, indicated the clientele compromised of three distinct groups of hackers: amateurs (red), professionals (green) and skilled non-professionals (yellow).

The low-impact trial plan was the most popular purchase. These users, which made up about 40% of the total customer pool, are very likely driven by the thrill of transgression rather than pure criminal intent.

A smaller group had more serious intentions, as their more expensive subscription levels indicated. Having invested more, they’d need a higher return on their investment.

Notably, we found the average yield for those involved was low, compared to yield obtained during other cybercrime operations studied. In fact, StressSquadZ operated at a loss for most of its life.

Two things help explain this. First, the service was short-lived. By the time it started gaining traction, it was shut down. Also, it was competing in a large market, losing potential customers to other similar service providers.

Complicit in the Act

While stressers can be used legally to test the resilience of security systems, we found the main intent to use StressSquadZ’s was as an attack vehicle against websites.

There was no attempt by the service provider to prevent clients from illegal use, thus making them a facilitator of the crime. This in itself is a crime under computer misuse legislation in most Australian jurisdictions.

That said, the group of criminals tapping into StressSquadZ was very different to a more archetypal and hierarchical criminal group, such as the Mafia. Without a “boss” StressSquadZ was sometimes disorganised and duties and benefits were more equally distributed.

We Now Face Fewer (but Stronger) DDoS Attacks

The emergence of DDoS stressers over the past decade has actually led to an overall reduction in the number of DDoS attacks.

According to CRITiCaL project, out of 10,000 cyberattacks between 2012 and 2019 – of which 800 were DDoS attacks – the number of attacks fell from 180 in 2012 to fewer than 50 last year.

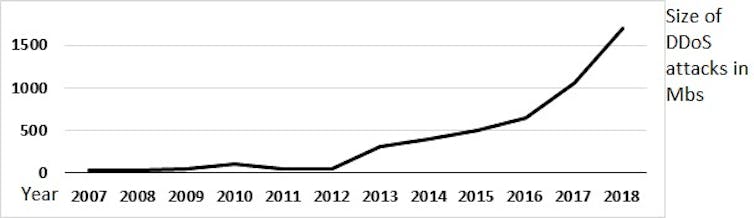

This may be because individual attacks are now more powerful. Early DDoS attacks were weak and short in duration, so cyber security systems could overcome them. Attacks today carry out their purpose, which it to invalidate access to a system, for a longer duration.

There’s been a massive increase in the scope and intensity of attacks over the past decade. Damage once done on a megabyte scale has now become gigabytes and terabytes.

DDoS attacks can facilitate data theft or increase the intensity of ransomware attacks.

In February, they were used as a persistent threat to seek ransom payments from various Australian organisations, including banks.

Also in February we witnessed one of the most extreme DDoS attacks in recent memory. Amazon Web Services was hit by a sustained attack that lasted three days and reached up to 2.3 terabytes per second.

The threat from such assaults (and the networks sustaining them) is of huge concern — not least because DDoS attacks often come packaged with other crimes.

It’s helpful, however, to know stresser providers use a business model resembling any e-commerce website. Perhaps with this insight we can get down to business taking them down.

Roberto Musotto, Research fellow, Edith Cowan University and David S. Wall, Professor of Criminology, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.