Table of Contents

Joe McIntyre

University of South Australia

Dr McIntyre is legal theorist specialising in judicial studies and public law. After initially practicing law in South Australia, he moved to the UK to study at the University of Cambridge. His doctoral thesis examined the nature of the judicial role, and how that role is both protected and constrained. He has held teaching roles in Australia, Canada and the UK.

Novak Djokovic is – at least for now – free to defend his title at the Australian Open after Judge Anthony Kelly of the Federal Circuit and Family Court quashed the cancellation of his visa following an agreement between the tennis star’s lawyers and the government.

After a confusing day-long hearing involving dense legal arguments, Djokovic was ordered to be released from immigration detention on procedural grounds – the judge said he hadn’t been given enough time to contest the original cancellation of his visa last Thursday morning.

But this left unresolved the bigger question of whether Djokovic was entitled to rely upon a medical exemption from Tennis Australia to enter the country and compete in the tournament without being vaccinated against COVID-19.

It is entirely possible Djokovic’s success in these proceedings is a hollow victory, with the government’s lawyer flagging Immigration Minister Alex Hawke will now consider whether to exercise his personal power to cancel the tennis star’s visa for a second time.

Grounds to Challenge the Visa Cancellation

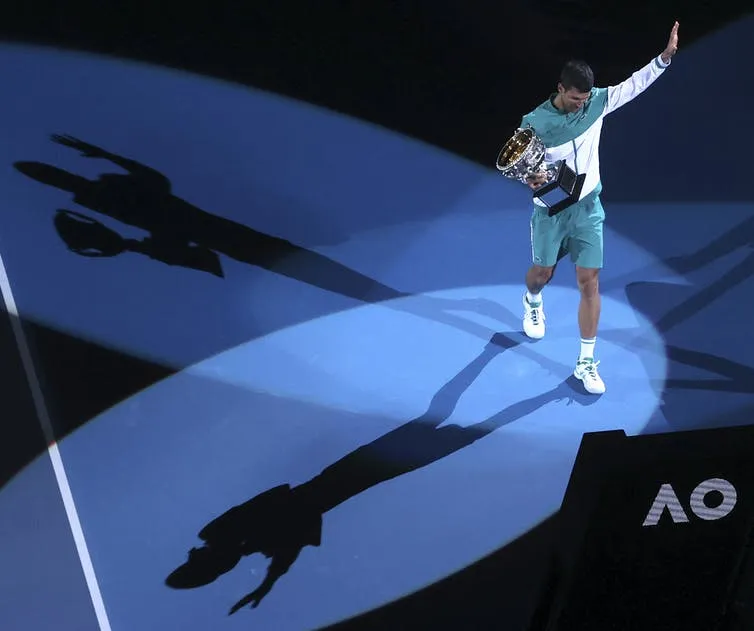

The saga surrounding the nine-time Australian Open champion has gripped the sporting world since Djokovic was detained upon arriving in Melbourne last week due to questions about his medical exemption from vaccination to play in the tournament starting on January 17.

Djokovic was moved to immigration detention in Melbourne’s notorious Park Hotel following the cancellation of his visa. His lawyers then lodged an application to challenge that cancellation through judicial review proceedings.

The process of judicial review allows a judge to examine the lawfulness of government decision-making. It is a limited process, not concerned with whether a right, preferable or fair decision has been made, but only whether the decision followed the proper legal processes and requirements.

Before the hearing began today, Djokovic’s lawyers had put forth eight distinct grounds for why, in their submission, the decision to cancel Djokovic’s visa was not lawful.

These included some technical issues, such as a contention the notice given to Djokovic to cancel his visa was invalid and the decision was based on nonexistent grounds under the Migration Act.

Similarly, his lawyers argued the process was unfair as Djokovic was “pressured” to agree to a decision on his visa without first consulting his lawyers.

The Bigger Question around a Medical Exemption

The substance of Djokovic’s challenge, however, revolved around his assertion that by testing positive to COVID-19 on December 16, he was exempt from any requirement to be vaccinated for six months.

His lawyers based this argument on guidelines set by ATAGI, the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, which said:

COVID-19 vaccination in people who have had PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection can be deferred for a maximum of six months after the acute illness, as a temporary exemption due to acute major medical illness.

In response, the government argued this approach was an inaccurate reading of the guidelines, saying that mere previous infection would not be enough to allow an unvaccinated person entry into Australia. In essence, the guidance provides for a deferment of vaccination, not a reason to avoid it altogether.

Moreover, the Commonwealth argued Djokovic’s reliance on the Tennis Australia exemption letter was misguided, and ultimately he did not provide sufficient information to justify entry without vaccination.

The medical exemption from Tennis Australia was a matter of significant disagreement between the parties. In the hearing, Kelly seemed to show some deference to Djokovic’s argument, saying:

Here, a professor and an eminently qualified physician have produced and provided to the applicant a medical exemption. Further to that, that medical exemption and the basis on which it was given was separately given by a further independent expert specialist panel established by the Victorian state government […] The point I am agitated about is, what more could this man have done?

The Commonwealth argued that irrespective of what Tennis Australia or the Victorian government may have decided, it is the federal government’s decision whether a visa ought be cancelled on public health grounds.

And this highlights the significant powers of the federal government in immigration matters, and that ultimately, according to the government’s court filings, there is “no such thing as an assurance of entry by a non-citizen into Australia”.

What Could Happen Next

Both sides agreed late in the day Djokovic hadn’t been given enough time to respond to the notification to cancel his visa. He was informed by border officials he would have until 8:30am on Thursday to respond, but his visa was cancelled at 7:42am. On this basis, Kelly ordered Djokovic to be released.

But the government’s lawyer immediately foreshadowed Hawke would consider using his personal power to cancel Djokovic’s visa again.

If such a decision is made, we should expect further litigation. Kelly said he expected to be “fully informed in advance” if he is required for future proceedings, ominously observing “the stakes have risen rather than receded”.

Kelly also noted Djokovic could be barred from re-entering Australia for three years if the personal power of the minister was used, though reports suggested this exclusion period could be waived.

For now, Djokovic is a free man. But it remains to be seen whether he will be spending the next few days on a tennis court or back in a federal court.

Joe McIntyre, Associate Professor of Law, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.