Table of Contents

This week, short of a major change to abortion laws, the biggest social legislative change in at least the last decade happened. New Zealand joined the growing list of places that have decriminalised the use and possession of drugs.

The passing of the Misuse of Drugs Amendment marks a significant shift in how the Government deals with the possession and use of controlled substances, especially for those caught in the web of addiction.

A last-minute wording change was needed to gain New Zealand First’s support, and National made a failed attempt at removing the entire pivotal clause.

Those changes basically mean an addict won’t be able to fake it in rehab just to avoid prosecution.

[…]The Misuse of Drugs Amendment Act has four core parts: the Class A reclassification of the two most prevalent chemicals found in synthetics, the ability to temporarily reclassify emerging chemicals, increased penalties for manufacturers and suppliers, and enshrining police discretion over prosecution, and prioritising therapeutic options when dealing with possession and personal use of controlled drugs.

Legislating police discretion is a remarkable move towards treating drug addiction as a health issue – something that’s been championed by the Greens and Labour, and agreed to in the parties’ confidence and supply agreement.

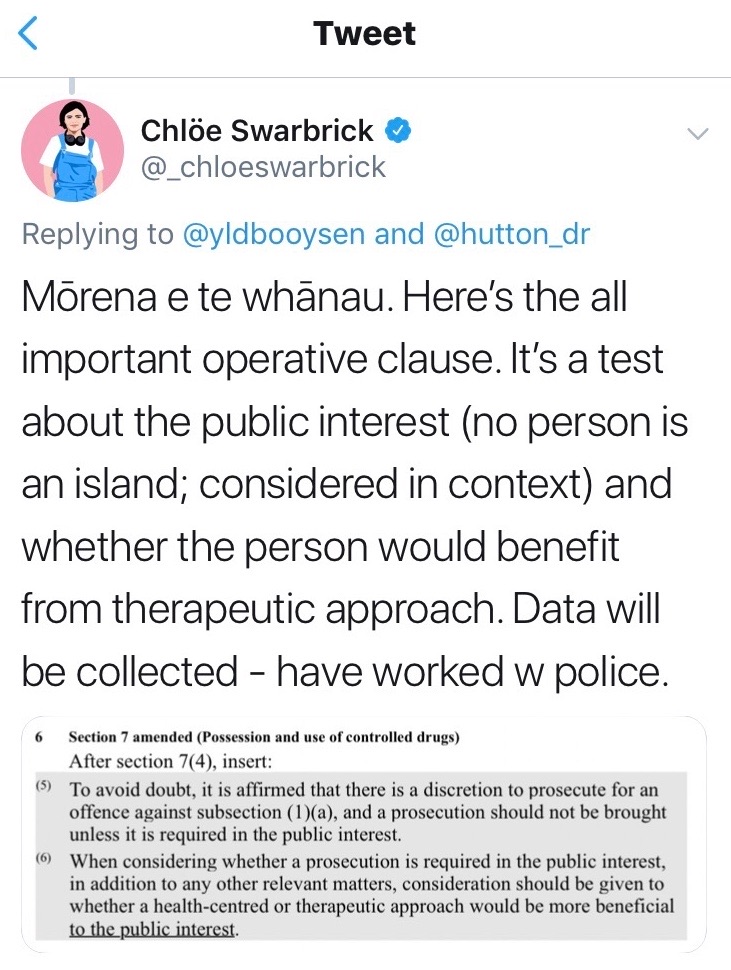

It’s a bit more than legislating police discretion. The changes mean that unless it’s in the public interest the police won’t prosecute for possession or use, or at least should not prosecute.

This is the same approach Portugal took when changing its drug laws in 2001. And it is a core recommendation of the national Mental Health and Addictions Inquiry.

Police already use discretion when dealing with cases of drug use and possession, but the new law clarifies the test police should apply, and allows for improved data gathering, which is expected to help create a fuller picture of drug use and addiction in New Zealand, including which groups are more likely to face criminal charges

As part of the law change the police have developed an application to use to determine when discretion should be applied and will also record data.

[…]On Tuesday night, New Zealand First issued a statement saying it had negotiated an amendment to the bill, “ensuring clarity for police officers when dealing with offenders found in possession of a controlled substance”.

The party said the change ensured a health-centred or therapeutic approach should only be taken where such an approach would be more beneficial to the public interest than prosecution.

This recognises that there will be addicts who either don’t want or are beyond help and will be back on the pipe as soon as they get out of therapy or rehab.

[…]Green MP Chlöe Swarbrick, who has been material in the creation and passing of the law, said the change would simply make crystal clear what had always been the case.

[…]The change clarified it was a public interest test being applied, rather than solely an individual interest test. So police would not be prosecuting those who suffered from addiction unless not doing so was at the expense of wider public

[…]The new law solidified and supported current police practice, and made sure they got resources freed up to go after the manufacturers and suppliers of drugs.

While it was a slightly messy end to the bill’s journey through Parliament, the three governing parties said they celebrated the passing of the law, with Swarbrick labelling it as “the most transformative change in drug law in New Zealand in over 30 years”.

“We’re living up to the rhetoric as a country that implements evidence-based policy, and one that prioritises compassion.”

[…]During the third reading, Paula Bennett questioned whether under-pressure mental health and addiction services had the capacity to take on more people. This is something also raised during the select committee process.

A valid concern but not a show stopper.

[…]Following the passing of the bill into law, Clark acknowledged the current need for mental health and addiction services outstripped the supply, but it was something the Government was focused on addressing.

The Government delivered a $1.9 billion package for a range of mental health and addiction services and responses in this year’s Budget, which included $459 million for primary sponsors aimed at addressing mild-to-moderate mental health and addiction needs.

“We’ll be building up those workforces, we can’t train all of the people we need overnight, it’s just not possible. We don’t have the capacity in the system to handle everything we want to do straight away, but we make no apology for getting on with it right now,” Clark said.

[…]For today, Clark is welcoming the significant step in using evidence to guide policy, and treating addiction with a therapeutic approach.

“It’s a day for some celebration because these issues affect real people’s lives,” he said.

Newsroom

Question is though, why should you care and what will it mean in practice? Most people don’t do illicit drugs but the misuse of drugs affects us all. There’s the cost to the taxpayer. There’s drug-related crime. If there’s something that reduces misuse and reduces drug-related harm then surely it’s a good thing that we try it.

What do the changes mean in practice? I don’t see it as providing a defence for driving stoned. My approach is strict liability until we have tests that measure impairment. That means if you have a bit of cannabis and get tested by the police driving the next day you get done even if you’re not impaired.

Needless to say, if you smoke meth in public you’ll still be done for possession and use. And if you use drugs in a State house (hopefully) you can be prosecuted as it’s not in the public interest for State tenants to use illicit drugs in State houses.

Most illicit drug use is non-problematic and done in private. In those cases, which is the majority, it isn’t in the public interest to prosecute.

Obviously, I think decriminalisation is a great move but whether it turns out that way remains to be seen. We can look at places like Portugal for guidance but not proof. A lot will depend on how much the government is willing to put in the health budget as we shift from a criminal justice approach to a health approach. A lot will also depend on how “public interest” is interpreted.

One thing is for sure. If after the changes no one now risks having their future ruined over having a single joint, and our taxes are no longer wasted sending them pointlessly through the justice system, then that is something worth celebrating.