Table of Contents

The Domestic Purposes Benefit has been variously described as a “disaster” (David McLoughlin 1995), an “economic lifeline” (Jane Kelsey 1995) and “an unfortunate experiment” (Muriel Newman 2009).

Its effect on family formation can never be definitively ascertained. But the growth of the sole-parent family dependent on welfare has correlated with more poverty, more child abuse and more domestic violence. Each of these was intended to be reduced by the introduction of the DPB.

The data

On the cusp of Generation X (born mid-to-late 1960s) the two-parent family was overwhelmingly the norm.

In 1966 there were 922,349 dependent children under 16 years of age. 883,239 depended on married men or 96 percent of the total. A further two percent (19,829) depended on widows or widowers. The remainder had unmarried, separated, divorced (and not remarried) parents, or were orphans.[1]

Fast forward to 2023.

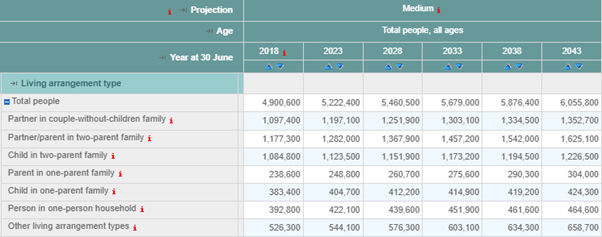

In lieu of pending census results, Statistics NZ projected population living arrangements (based on medium fertility, mortality and migration) predicted there would be 5,222,400 people living in New Zealand, which is pretty much on the button. These would include 641,000 couples with 1,123,500 children, and 248,800 sole parents with 404,700 children. Therefore, 73.5 percent of children live with two parents, not necessarily biological or married. Fewer than three quarters. It is important to note that not all of these ‘children’ will be under 18.

This less-than-perfect comparison between family composition in 1966 and 2023 nevertheless serves the broad purpose of illustrating the stark change that has occurred. And while just under three-quarters of children living with two parents still represent a majority, an associated socio-economic gradient means that in the most deprived neighbourhoods, the proportion is much lower.

Why did the change occur, and what role did politics play?

Governments rightly respond to public demand for legislation to accommodate evolving attitudes and practice. But that response can, in turn, accelerate the pace of change. It is said that governments ‘get what they pay for.’ Certainly, a government with a particular agenda – proactive as opposed to reactive – will deliberately use legislation to incentivise the change they want. But unintended incentives also arise with legislation introduced, for example, to alleviate what is thought to be a temporary or minority need.

This chicken-and-egg chain of events characterises the beginning of the decline of two parent families as the norm.

1960s

Throughout the 1900s births outside marriage were steadily increasing. The rate grew from 8.93 (per 1,000 unmarried women) in 1911 to 40.63 in 1966. That year 11.5 per cent of all births were what was commonly called ‘ex-nuptial’.[2] While many of these babies were adopted out to strangers, increasingly they remained with their mother or cohabiting parents. Not only was it getting harder to find adoptive families, but the tide of sentiment was turning against the practice. Feminist dogma maintained the child belonged with its biological mother without exception. Biological fathers were not accorded the same priority.

Young women – and men – were rejecting the conventions and constraints complied with by earlier generations. Some viewed marriage as a restrictive, archaic institution.

Researcher Kay Goodger writes:

“The reasons for the increase in ex-nuptial fertility in the 1960s … include the large increase in the number of unmarried women in the younger reproductive age groups as the post-war baby boom generation reached adolescence; the increased mobility and autonomy of youth; a rise in pre-marital sex combined with relatively poor access to birth control; and a decline in the practice of marrying because of pregnancy.”

Goodger also notes that although the contraceptive pill became available in 1961 there was initial reluctance to prescribe it to unmarried females.[3]

Add into the mix the urbanisation of Maori and their more liberal attitudes to marriage and childbearing. In 1969 the Status of Children Act removed the discriminatory term ‘illegitimate’ which had never been applicable in Maoridom.

Widows had long been supported through social security benefits which begged the question why other single mothers weren’t similarly helped. As society’s collective (though not consensus) moral view shifted from stigmatising to sympathising with sole parents a policy response became inevitable.

Under a National government, from 1968 a Domestic Purposes Emergency benefit became available, but was not an automatic entitlement. Social welfare case managers could approve an emergency benefit to a sole parent at their discretion. Discretionary granting wasn’t a radical concept at that time. Historically old age and invalid pensions were subject to character tests.

1970s

But the numbers receiving this emergency benefit grew rapidly and the 1972 Royal Commission on Social Security recommended a statutory benefit replace it. That came into being on November 14, 1973 under an incoming Labour government (having been hurried along by a National private member’s bill to the same effect.) Relegated to page 18 of the capital’s evening newspaper under the headline, “Rights of appeal, and benefits for all solo parents in new welfare act,”[4] its advent was barely newsworthy.

What mattered was a sole parent of either sex now had a statutory entitlement to the new benefit regardless of the reason for their sole parenthood. Journalist Colin James noted, “The creation of the domestic purposes benefit made it much more practicable for women to leave unsatisfactory (or unsatisfying) relationships in which otherwise they might have stayed.” [5]

Writer Michael Belgrave describes this shift as the morality-based welfare state being replaced with the rights-based welfare state.[6] Human rights grew ever broader, and the guarantee of meeting those rights led to state support entitlement. The concept of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ beneficiaries was losing traction. Michael Jones wrote that, “… the rights movement, popular in the 1970s and 1980s, reduces or even eliminates any sense of shame at being in receipt of benefits.”[7]

The proportion of children without two cohabiting parents grew quickly thereafter. “Children with a parent on DPB increased from 4% of all children under 18 in 1976, to 17% in 1991, and to 19% in 1996.” [8]

As early as the late seventies alarm bells started to ring. Measures to disincentivise applications (like compulsory marriage counselling) were introduced but unsuccessful in stemming growth in recipients and cost to the state.

1990s

No fault divorce was introduced in 1980, with no court hearing required from 1990, further easing the pathway to separation. Compounding this development was a deep recession which saw unemployment rise to 11 percent in 1992. For purely pragmatic reasons decisions to separate were based on accessing two incomes instead of one. Jane Kelsey explains, “Perversely, because benefit eligibility reflected individual circumstances, and benefit rates and means testing were based on family income, many families were better off financially to separate.”[9] One parent would claim the DPB while the other claimed the unemployment benefit. (From 2004 it became possible for separating parents to split the custody of their children and both claim the DPB. Activists fought for this law change because the DPB had a higher payment rate and other more favourable conditions.)

As an aside, the practice of living apart for the purpose of collecting benefits continues to make measuring genuine sole parenthood fraught. In 2019 Auckland University of Technology researchers wrote: “We find that 70% of those who say they receive the domestic-purposes benefit also answer yes to the question of whether they have a partner – confirming that the sole-parent status derived from GUiNZ [Growing Up in New Zealand] is essentially different to those studies which rely on benefit status to infer partnership status.”[10]

While separation and divorce were the most common causes of sole parenthood MSD acknowledges that, “A second contributing factor was an increase in the number and proportion of pregnant single women who did not marry or place their child for adoption.”[11]

Throughout the 1990s DPB numbers exceeded 100,000.

In 1997 State Services Minister Jenny Shipley stated, “I want every child to be a chosen child”.[12] Oral contraceptives became fully subsidised and over time, contraception has only become more accessible and more effective.

2000s

Under Helen Clark’s Labour government (1999-2008) more single mothers moved into part-time work and receipt of the In Work Tax Credit. But the Global Financial Crisis (2008-11) saw a resumption of growth in DPB numbers after which they fell steadily again under John Key’s National government. The latter drop was substantially aided by the plummeting teenage birth rate (a significant feeder into long-term dependency ranks) but also more stringent work-testing. The carrot-and-stick approach contributed to a steadily increasing sole-parent employment rate.

Then in 2013 the DPB quietly ceased to exist. Unfortunately, this was no more than a modernising of the benefit name to Sole Parent Support with some eligibility adjustments resulting in a transfer of some from DPB onto other benefits.

Post 2017

An upward trend resumed after Ardern took office in 2017 and began steadily increasing benefit payments and child tax credits. Currently, there are around 75,000 on Sole Parent Support but over 100,000 sole parents across all main benefits. The number of children reliant on Sole Parent Support grew by 35,000 or thirty per cent between September 2017 and September 2023.

Ardern also oversaw other controversial legislative changes which further undermined the responsibility of fathers. For example, single mothers on welfare are no longer financially penalised if they fail to name the father of their child(ren).

When confronted with evidence that child poverty strongly correlates with family structure (sole parents are the poorest family type) Ardern was dismissive.[13] Like her recent Labour predecessors, MSD Minister Steve Maharey in particular, she refused to acknowledge the importance of nuclear families.

Yet at some point in the not-so-distant past, politicians and public servants recognised the concept of family as the fundamental social and economic unit and were extremely reluctant to undermine its formation and stability. How times have changed.

The Present and the Future

Right now, benefit-dependent single parents are on the rise again. They proliferate in emergency housing. Single parents have the lowest home ownership rates and the highest debt-to-income ratios.

Police report that family violence is at record levels – single welfare-dependent females are the most vulnerable to partner violence according to victim surveys. The correlation between substantiated child abuse and appearing in the benefit system is incredibly strong.

Child poverty now drives both a public and private industry of people who claim to be helping to alleviate poverty. There are domestic child sponsorship programmes, KidsCan, Variety, etc. Forget famine-stricken African nations.

While benefits became more generous, easier to access and stay on under Ardern’s regime of “kindness”, any remaining obligations to the taxpayer became passe. There is no sign whatsoever that a resumption of deserving and non-deserving considerations will make a comeback. In fact, morality is ever more remote. Widows who become sole providers through no fault of their own are no longer differentiated from gang women who produce children as meal tickets. No distinction is made between reasons for ‘need’ and the taxpayer is expected to like it or lump it, despite the fact that fifty years of trying to solve social problems with cash payments has only made them worse.

American sociologist Charles Murray wrote about the identical welfare challenge in the US, “When reforms do occur, they will happen not because the stingy people have won, but because generous people have stopped kidding themselves.” [14]

[1] New Zealand Official Yearbook 1973, p77

[2] New Zealand Official Yearbook 1973, p91,92

[3] MAINTAINING SOLE PARENT FAMILIES IN NEW ZEALAND: AN HISTORICAL REVIEW, Kay Goodger, Social Policy Agency, https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj10/maintaining-sole-parent-families-in-new-zealand.html

[4] Rights of appeal, and benefits for all solo parents in new welfare act, Evening Post, p18, December 1, 1973

[5] New Territory, the Transformation of New Zealand 1984-92, Colin James

[6] Past Judgement, Needs and the State, Michael Belgrave, 2004, p32

[7] Reforming New Zealand Welfare, Michael Jones, 1998

[8] MAINTAINING SOLE PARENT FAMILIES IN NEW ZEALAND: AN HISTORICAL REVIEW, Kay Goodger, Social Policy Agency, https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj10/maintaining-sole-parent-families-in-new-zealand.html

[9] The New Zealand Experiment, P279, Jane Kelsey

[10] Protective factors of children and families at highest risk of adverse childhood experiences: An analysis of children and families in the Growing up in New Zealand data who “beat the odds” April 2019, https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/children-and-families-research-fund/children-and-families-research-fund-report-protective-factors-aces-april-2019-final.pdf

[11] Economic Wellbeing of Sole-Parent Families, November 2010, Families Commission

[12] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/minister-urges-new-zealanders-take-responsibility-sexual-health

[13] https://lindsaymitchell.blogspot.com/2016/06/jacinda-ardern-in-sst.html

[14] Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950-1980