Table of Contents

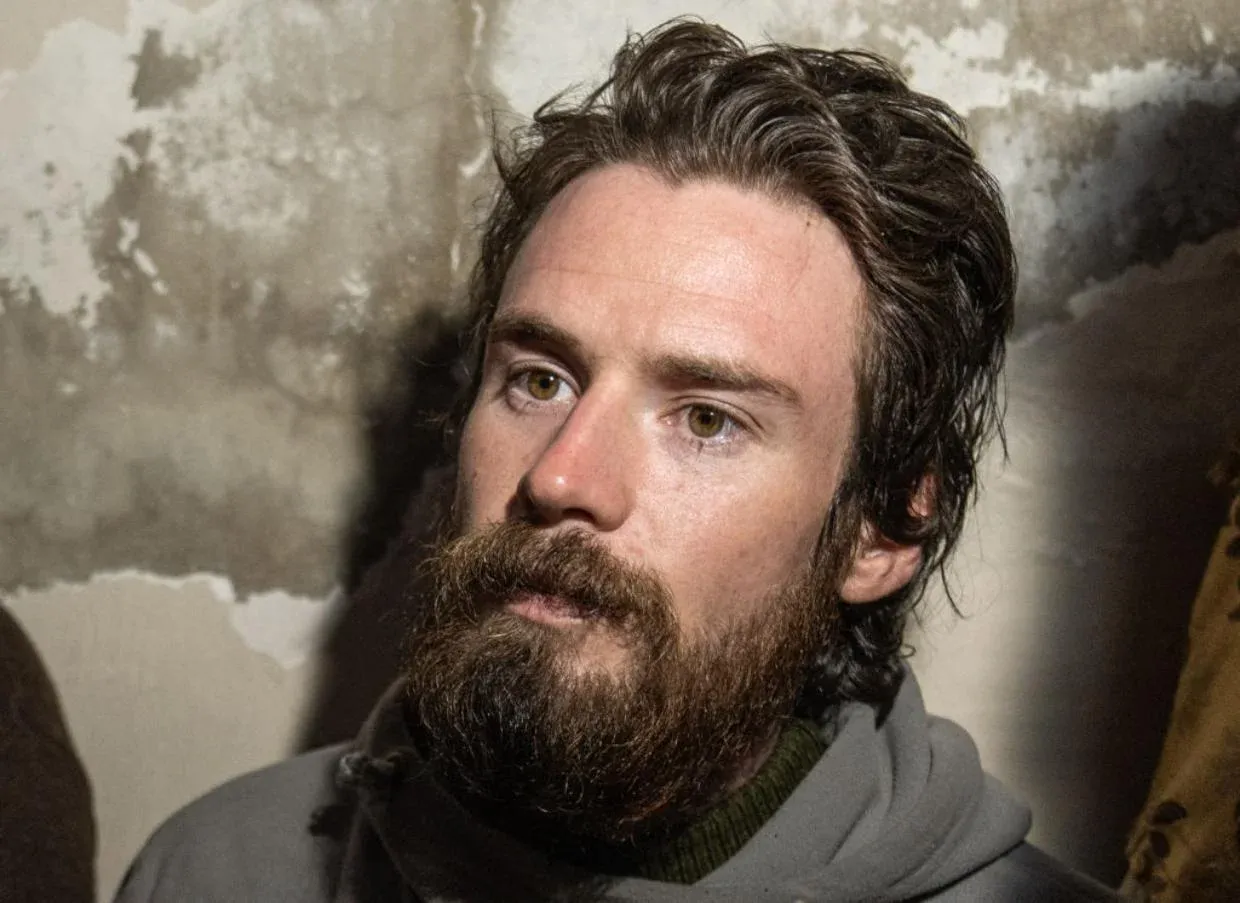

Duncan McLean

Sciences Po Toulouse

Duncan McLean is a fellow at Sciences Po Toulouse, lecturing on the history and contemporary challenges of humanitarian aid. He is also senior researcher with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), based out of the Research Unit on Humanitarian Stakes and Practices (UREPH) in Geneva.

Lying a few kilometres off the Turkish coast, a series of Greek islands remain on the frontline of increasingly militarised attempts to limit the arrival of migrants and asylum seekers to the European Union. The often unseen and largely ignored treatment of those seeking shelter, whether pushed back to Turkey or incarcerated in isolated camps for processing, compound their suffering and make a mockery of protections ostensibly provided under refugee law.

Europe’s “pushbacks”

Individuals and families who make landfall in Samos and Lesvos, often hiding from the authorities, are offered emergency medical and psychological first aid by teams from Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. High levels of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder reflect both the experience that led to their making the high-risk journey to Europe, and the ordeal of the journey itself. Violence is common and survivors regularly report having been forcibly returned to Turkish waters. In recounting the dread of being pushed back yet again, a former patient said, “you feel like dying.”

The term pushback has been described by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights of migrants as measures that result in “migrants, including asylum seekers, being summarily forced back” without assessing their protection needs, to their point of crossing, be it land or sea. While this essentially covers deportation and refusal of entry, it should not be confused with the concept of refoulement, which refers to the expulsion of an individual to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened. While refoulement is illegal under customary and international law, pushbacks occupy a judicial grey area.

The fact that pushbacks are taking place on Europe’s borders is no longer in question. German media recently made public a redacted but sufficiently detailed report by the EU’s fraud office outlining complicity on the part of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) in the pushback of migrants from Greece to Turkey. Operating under the command of the Greek authorities, Frontex was deemed to have actively covered up pushbacks by the Greek navy either by avoiding the area where they were taking place or simply not investigating.

28,000 people adrift in the Aegean Sea

That such actions represent an extreme danger for those desperate enough to risk the crossing into Greece is likewise not in dispute. The term drift-backs has also been used to describe this method of violent deterrence, essentially forcing migrants and asylum seekers into motorless rafts to drift on the currents back to the Turkish coast. Forensic Architecture estimates that around 28,000 people have drifted across the Aegean Sea in a two-year period since the first case was documented in February 2020. Cynically effective, the Greek government has presented reduced arrivals as a success, even as mortality has proportionally increased.

Given some of the more egregious approaches to manipulating migrant flows, and the very human desperation that drives them, the ascendance of pushbacks is sadly not alone as per shady practices. Other recent examples include Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko’s facilitating the arrival of asylum seekers from the Middle East as a retaliation over EU sanctions and Morocco’s punishing Spain for providing medical care to the leader of the Sahrawi liberation movement by “engineering” a surge of migrants into the enclave of Ceuta. Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was a master at securing political and economic concessions by playing on European migrant fears.

Outsourced border controls in Turkey and Libya

In the years that followed the 2015 arrival of 1.3 million asylum seekers, those same fears have led to the preferred EU approach of outsourcing border controls, including asylum applications when feasible. Despite these measures and the billions that have been paid to Turkey, people continue to risk their lives. In 2017, European states began funding Libya’s coast guard, even with well-documented concerns over treatment during Mediterranean interceptions and conditions in Libya itself. The stalled plan to send asylum seekers from the United Kingdom to Rwanda is a striking example of rich countries attempting to pay their way out of shared responsibility for refugees. Preventing migrants from crossing over from a bordering country to Greece’s actively pushing them back is simply another step toward the militarisation of what is fundamentally a humanitarian issue.

Other heavy-handed measures have accompanied pushbacks. For those who manage to reach the island of Samos, transfer and detention in the Closed Controlled Access Centre awaits. Military-grade security measures are accompanied by lengthy legal procedures often resulting in the rejection of asylum claims and dehumanising experience for applicants. As for the process itself, much like pushbacks at sea both have become “a test ground for Europe” according to Christina Psarra, the general director of MSF-Greece.

An increasingly hostile political climate

Such deterrence and containment policies regrettably fall into the mundane and engender little debate in a highly polarised political environment. Search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean that were previously lauded are now accused of colluding with people smugglers, ports are regularly closed to overburdened boats carrying rescued migrants, and acts of solidarity are criminalised. And a populist narrative of “Europe under threat” conveniently ignores those who are perishing unseen in quasi-militarised zones inaccessible to journalists and aid workers, or languishing in detention camps, outsourced or otherwise.

It is hardly a revelation to note that the granting of political asylum can be discriminatory, the preference for political dissidents from enemy countries over those fleeing conflict in the Global South being an obvious case in point. More recently, the double standards displayed in the reception of Ukrainian refugees, what has been referred to as selective solidarity, is incomparable to the experience of those who arrive in Greece and elsewhere in Europe.

More broadly, the dilution of refugee law in Europe is part of a disturbing trend where international humanitarian obligations are ignored at will. Systematically and consciously endangering the lives of asylum claimants and refugees while leaning on the supposed “dangers” posed by economic migrants challenges our basic humanity.

Condemning criminal practices such as pushbacks is relatively straightforward given the loss of life, and the EU has done this through its own fraud office and more recently in a report from the Council of Europe. The bigger task is fixing a broken system that has spent millions of euros reinforcing the EU’s response to migration while paying off poorer states to manage the problem – this is especially distasteful given the small percentage of global refugees actually residing in Europe. Dignified access to safe reception, protection and asylum procedures is the minimum required under international law. Europe has demonstrated this capacity in the past; unfortunately, the political will appears to have been forgotten, or worse.

Duncan McLean, Senior researcher, UREPH-Médecins Sans Frontières, fellow, Science Po Toulouse, Sciences Po Toulouse

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.