Table of Contents

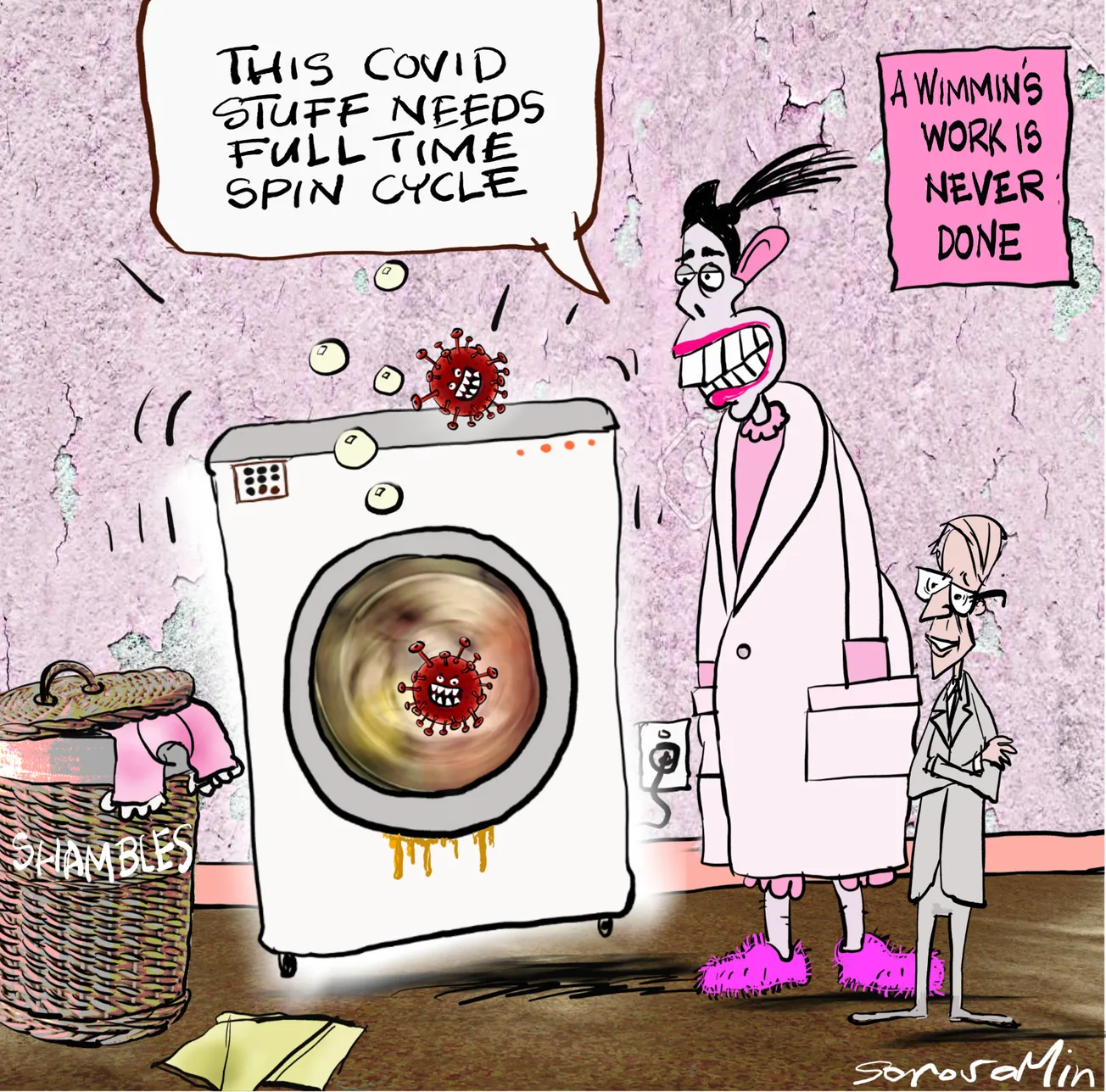

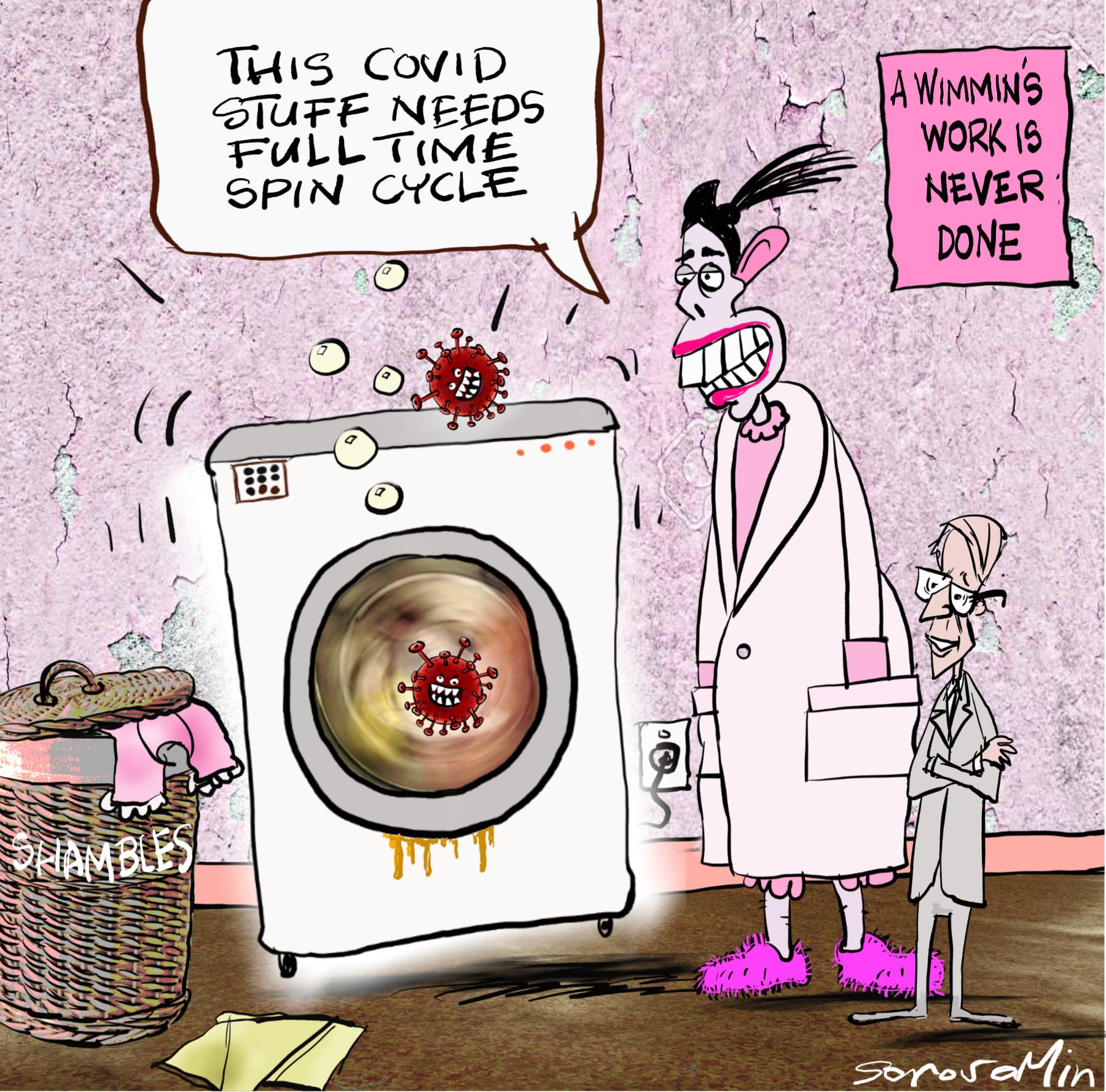

It seems odd that people are leaving quarantine hotels, otherwise known as Managed Isolation Facilities, with COVID-19. Speaking as someone currently interned in one, it is also very disturbing.

In any western liberal democracy, quarantine hotels are a gross outrage. It is beyond the pale that a socialist government which opposes prisons and refuses to prosecute or punish many serious crimes, is perfectly prepared to imprison, without trial or the right to appeal, large sections of the law-abiding population for the sole misdemeanour of having travelled overseas.

The government and its media accomplices are stoking a nation-wide climate of fear which is shameful. As a result, once my incarceration was made known, I started receiving requests that, upon release, I should not attend certain business premises on the grounds that ‘people are uncomfortable’ and I ‘might have COVID’.

Can you even begin to imagine the incendiary reaction which would ensue if someone were to say, on alleged health grounds, that they are uncomfortable meeting a homosexual because he might have AIDS? What on earth has happened to us? It is as if our humanity and our senses have completely drained away.

I can’t complain that I am here because I knew this to be the consequence of travelling. If you do the ‘crime’, you must be prepared to do the time. However, there are a number of practical reasons, quite separate from the moral objection above, as to why quarantine hotels are not good for us.

The first is the shepherding of the healthy into a ‘plague ship’ environment where people are known to be ill.

When I arrived in the Middle East a month ago, I was asked at the airport to take a COVID test and isolate at home until the result arrived. This gave me the advantage of going to a clean domestic environment where I knew I would only be with people who were well. Twelve hours later I was cleared to go out. This is despite countries in the Gulf having between 300 and 3,000 active COVID cases at that time.

When Middle East countries have, intermittently, imposed longer home quarantine restrictions on travellers, the requirement has been met with an extremely high level of compliance because those countries have a strong rule of law and, with their homogenous and tight-knit local populations, a strong sense of the Social Contract.

It is only because we have deteriorated to the point where our population is both lawless and clueless (unrestrained, infantilised and indoctrinated in Marxist ‘rights’) that we would even consider imposing this form of penal servitude upon the innocent in order to protect the wicked and the foolish from themselves.

From what I have seen of this twenty-first century asylum (the reception, my cell, the ballroom where the nurses do their probing, and the exercise yard – where prisoners trapse forlornly in a circle) it is obvious that the greatest risk of catching COVID-19 which I have ever faced is right here.

These are just some of the reasons why:

The building was a 5-star hotel. It was not designed for a long-stay population. Food is delivered to rooms in disposable containers and eaten off plates and cutlery which remain in the room, to be washed by hand in the bathroom sink using the bottle of Cussons Morning Fresh provided. Many of these 35 m2 rooms contain families of three or four people who share the bathroom and wash their dishes in the same sink used for handwashing after going to the toilet or moving around the hotel. This is a situation much more akin to Victorian tenement living than a clinically hygienic environment.

If a roommate is unwell, others are at greater risk of contagion than they would be at home where people can be isolated in separate rooms. What’s more, there are far greater numbers of people visiting (meal deliveries, nurses, hotel staff) than there would be at home.

The hotel is hermetically sealed and air-conditioned. It’s a 1980s building which was probably built by a developer on a very tight budget. I’m not saying that the ancient ventilation system, which can be seen rusting away above the inmates’ yard, isn’t fit for purpose. But neither was it designed to run at 100 per cent capacity, 24 hours a day in a health isolation facility. COVID-19 is an airborne illness. Full natural ventilation would be hugely preferable.

Access to stairs is prohibited and vertical transportation is via lifts under the stewardship of the Navy. As only one ‘bubble’ is allowed in a lift, long periods are spent waiting in the unventilated lobby and pawing buttons, which don’t work properly because of the heavy demand and constant abuse they receive. I privately refer to this airless quarter as ‘COVID Central’.

Nurses, staff and military supervisors operate in a sterile environment, often behind glass, and with full PPE. The assumption from this can only be that internees do not exist within the same sterile, or wholly safe, environment. This is also perhaps why the room isn’t cleaned for the entire duration of the two week stay.

There is a behavioural aspect also. Many people, especially those of us who have never been to jail, find all this very daunting. You can tell who’s new in the yard by the distress in their eyes. Many inmates prefer to remain locked in their rooms where at least they are not staring at security fences and being surveilled by prison guards.

Everyone is told on the first day that the reformatory operates on a penalty system. The sanction for poor behaviour – not wearing your blue wristband, not wearing PPE, refusing a COVID test and, presumably, being ‘lippy’ – is a longer stay. When an inmate catches COVID, as I saw on my second day, the facility goes into lockdown, prisoners are confined to their quarters and the premises are ‘deep cleaned’.

There are no actual cleaning products inside the rooms, however: no handwash, no disinfectant spray, and no wipes. I had to order these in from Countdown.

With the tremendous stigma attached to testing positive – the loudspeaker announcements, the confining to barracks, and the very real possibility that the unfortunate soul concerned could be transferred somewhere even worse, it should come as no surprise that some people might suppress their symptoms if they had them.

It should also come as no surprise that some people who leave this facility might go bonkers, get a tattoo, go on a pub crawl or tour Northland. That’s the sort of thing the freedom-deprived do. The nurses know this, because the question most commonly asked is not about COVID at all, but rather: how is your mental health?

Perhaps it’s not COVID that we should be worried about, but rather what happens to all of these patients once they are released from the set of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Please share this BFD article so others can discover The BFD.