Table of Contents

In his A Short History of Christianity, Geoffrey Blainey considers the question of Jesus’ existence. As Blainey points out, the very fact that roughly contemporary records exist of someone so obscure as a carpenter-turned-preacher in the Roman boonies is a remarkable fact in itself.

Historical records, until at least the pre-modern era, are almost exclusively concerned with the doings of kings and generals. Ordinary folk barely rate a mention.

So the ruins of Pompeii are all the more remarkable in that they give us an insight into the ordinary Roman-in-the-street: often in their own words.

When Vesuvius erupted, nearly 2,000 years ago, it buried a then-vibrant, diverse Roman city almost instantly, preserving its streets and homes almost intact.

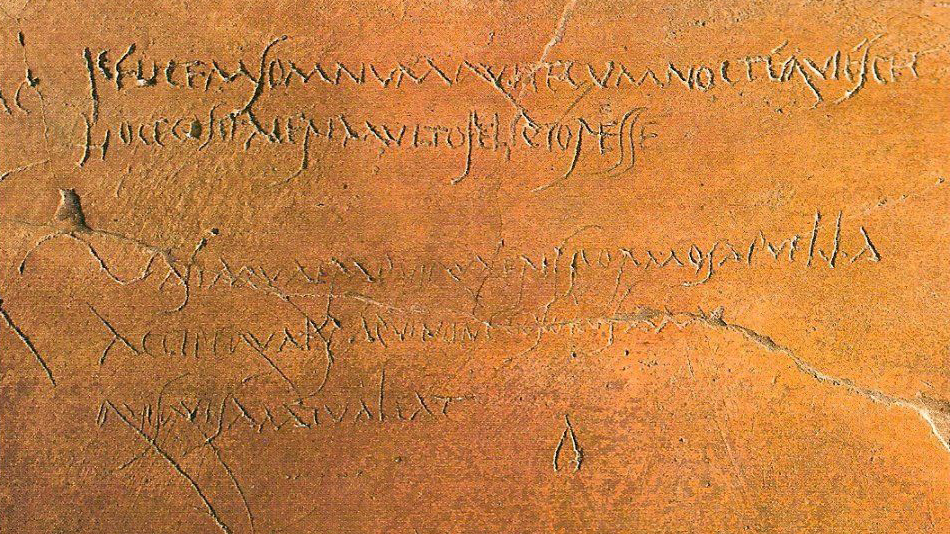

Including its prolific graffiti.

Though over 90 percent of the humerus [sic], banal, and occasionally cruel words have faded over time, fortuitous cataloging from the 1800s and modern excavations have left scholars with much to study about the daily life and personal politics of the empire’s subjects as scrawled on public walls.

Ancient Roman graffiti in Pompeii runs a relatable gamut, from flattering portrayals of the city’s prostitutes to insults aimed at foes, from praise for friends or political figures to the simplest declaration of personal presence.

The graffiti of Pompeii could be said to be the original vox populi.

Pompeii itself was only rediscovered by builders constructing a palace for the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon, in the 1700s. In the centuries since, archaeologists have found ancient Roman graffiti unlike any other.

The Roman graffiti in Pompeii is as varied as any found in modern cities. The oldest known scrawl was a humble yet determined demand to be acknowledged: “Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here.” The reason researchers know it is the oldest is that Gaius helpfully included a date when he was there, equating to Oct. 3, 78 B.C.

The simple declaration I was here seems to be one of the oldest human impulses. It’s somewhat heartwarming to know that the graffiti I see celebrating New Year 1973 is part of an ancient tradition.

Many individual pieces of Pompeii graffiti are endearing declarations of well wishes, like one resident who found a wall on which to write, “Health to you, Victoria, and wherever you are may you sneeze sweetly.”

Some graffiti provides insights into how Romans thought about and treated death, less as a conclusion and more of a farewell: “Pyrrhus to his chum Chias: I’m sorry to hear you are dead, and so, goodbye!”

Not all of it is so kind, however. “Sanius to Cornelius: Go hang yourself!” reads one man’s challenge to another.

Other graffiti covers the gamut of human emotions. “If anyone does not believe in Venus, they should gaze at my girl friend.” “Theophilus, don’t perform oral sex on girls against the city wall like a dog.” “Chie, I hope your hemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than when they every have before!” “Apollinaris, the doctor of the emperor Titus, defecated well here.” “Epaphra is not good at ball games.” “Stronius Stronnius knows nothing!”

Another startling discovery at Pompeii was its well-preserved frescoes of such explicit nature that they were locked away from public view for nearly 200 years after the city was excavated. The erotic artwork includes household items and the famous brothel, with its painted advertisements of the delights on offer.

But more revealing is what is written in the walls of the individual rooms.

One woman claimed her status as “Murtis Felatris,” or Murtis, Queen Felator. Using a masculine verb for what ancient Romans considered a feminine act, Murtis subversively, and subtly, rewrote her role in Pompeii society.

For such an obviously horny lot, the Romans still had their hang-ups. Which included strict gender roles. Despite the a-historical attempts of gay marriage advocates to yoke the Romans to their cause, the fact is that the Romans were pederasts who would have been appalled by modern gay relationships. Nero’s own gay marriage was explicitly cited by Seutonius as a prime example of the emperor’s degeneracy.

The Romans were also pretty hung-up about oral sex. It was mostly something that women did to men. So, as noted about, the long-gone Murtis using a masculine verb to advertise herself as, literally, a blow-job queen, is pretty daring stuff.

But a very recently uncovered graffito may also re-write the historical record.

Pliny the Younger, an eye-witness, explicitly dates the eruption of Vesuvius as occurring on the sixth day before September in 79 A.D.

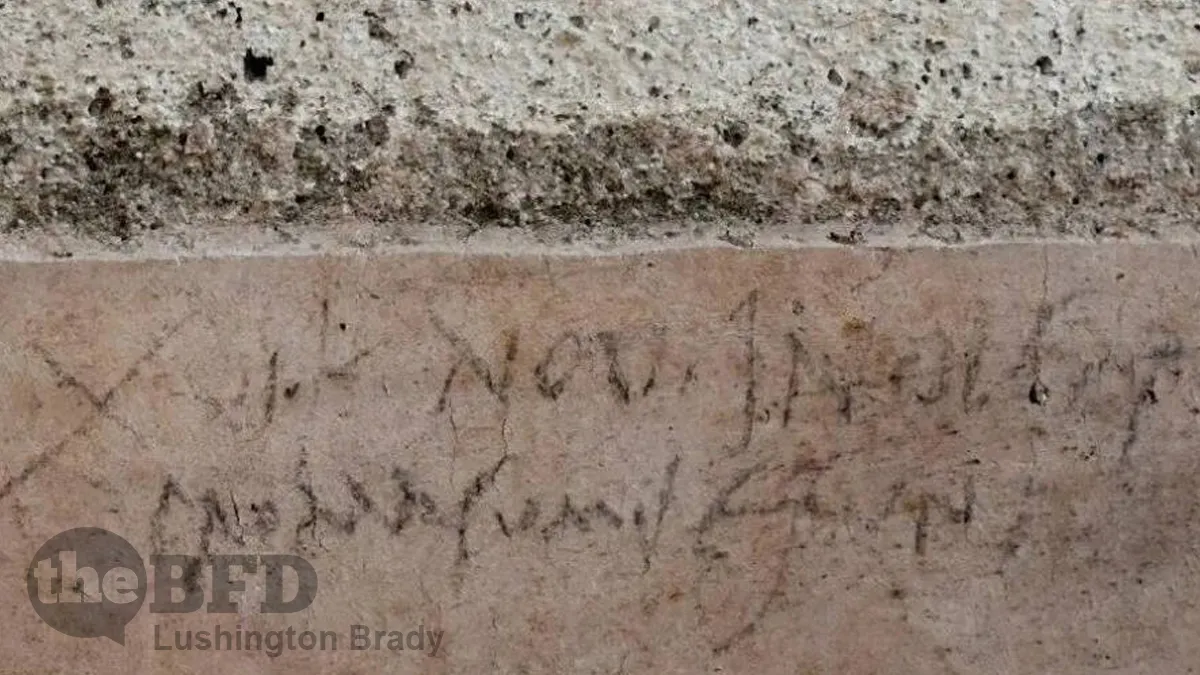

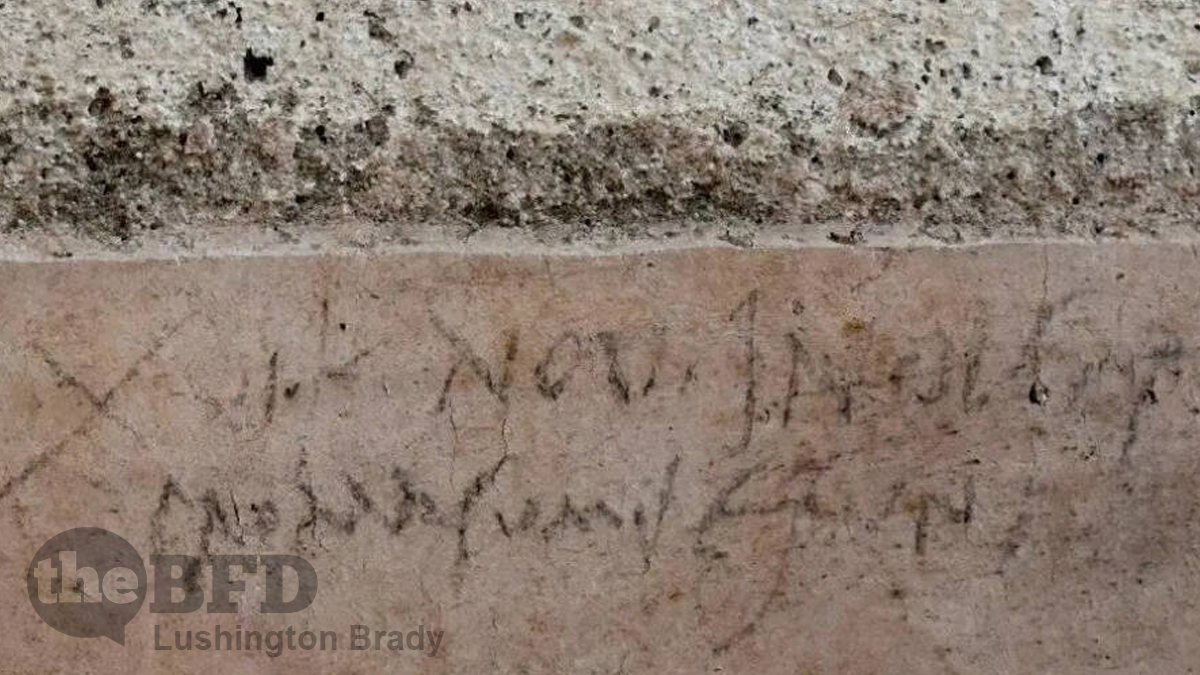

In 2018, excavations in Pompeii’s Regio V area revealed a charcoal inscription that baffled experts. The writer dated it “XVI K Nov,” the 16th day before November, two months after Pliny the Younger said Mount Vesuvius covered the town in 19 feet of debris.

All That’s Interesting

Pliny wrote his letter describing the eruption about 25 years after he watched it happen. So he could be forgiven, perhaps, if his memory played tricks on the exact date.

Meanwhile, the graffiti of Pompeii remains as a mute testament to those ordinary folk, two millennia ago, who wanted us to remember that they were there.

“Aufidius was here. Goodbye.”

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD