Table of Contents

Peter Doyle

London South Bank University

Professor, London South Bank University; PhD geology; geology, military geoscience and military history research background; Secretary of the All Party Parliamentary War Heritage Group; British Commission on Military History member; author of 41 books (military history, geoscience) and numerous papers on geology, military geology, conflict archaeology and military history.

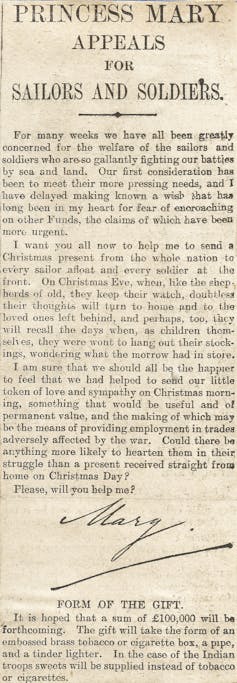

I want you all now to help me send a Christmas present from the whole nation to every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front… Please will you help me?

HRH Princess Mary, October 15, 1914

This is a lovely gift, and I am sending it home that you may keep it safe, for I would not part with it for anything in the world.

Driver W Powell, Army Service Corps, February, 1915

Anybody with a passing interest in the first world war will have heard of the “Princess Mary tin” – a gift from a 17-year-old princess for sailors battling fierce seas and soldiers mired in winter trenches in 1914. Among the backdrop of the unofficial truces that were held up and down the line on Christmas Day 1914, this simple gift has assumed almost mythical proportions. It is a potent symbol of a moment of peace in a deepening war.

From India to Canada, Australia to the UK, these neat little brass boxes bearing the profile of the young princess can be found in drawers and cupboards across the world. Some contain memories and mementos of war which have been cherished for over 100 years.

Mohammed Babavali’s box is a proud legacy which he will pass on to his children. The tin, awarded to his great-grandfather for his service in Flanders Fields, was one of the few family heirlooms salvaged by his father after a cyclone hit their village in western India in 1977. Though the tin is empty, for Babavali it is “filled with memories”.

This is a common reaction. Yet all too often these memories have faded, becoming fuzzy tales at the end of even fuzzier internet searches. The truth behind this unparalleled and hugely expensive charity campaign has never been fully told. Until now.

I examined all the available evidence and worked with archivists at the princess’s former home, Harewood House, the Imperial War Museum and other notable repositories and archives. My research has uncovered the true motivations behind the scheme as well as revealing some surprising and previously unknown facts.

I discovered how the executive committee that delivered the gift was not just made up of powerful men – it included senior women, who materially influenced its outcome.

I also found that although the scheme was designed to supply 500,000 gifts, in actual fact, the success of the fundraising meant it was extended – amounting to 2.6 million gifts worldwide, to be presented to all those in the “King’s uniform” on Christmas Day 1914. But assembling the gifts was a huge undertaking, and distributing them became a massive burden on the army.

To understand the story, we must first understand the time – and the young princess at its centre.

‘The first modern princess’

When the world was in the grip of 1914’s “Great War”, Princess Mary was just 17. The only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, she was bright, well educated and capable of holding her own among her brothers. But Mary was not one to play upon her fresh, natural demeanour. With no time for stuffy formality, the princess dedicated herself to war work and ultimately became interested in giving a Christmas gift to all those fighting.

Elisabeth Basford’s recent biography of Mary (the first for a century) has cast new light on this reticent, shy but dedicated young woman. Basford rebranded her as the “first modern princess” and my own findings have backed this up.

This remarkable story began with a simple appeal to the nation. On October 16, 1914, the press announced an idea embodied in a simple letter: a letter full of genuine pathos; a letter penned by the young princess herself. In it, with youthful sentiment, Princess Mary announced her Christmas gift for all those sailors and soldiers serving in the theatres of war. She wrote:

For many weeks we have all been greatly concerned for the welfare of the sailors and soldiers who are so gallantly fighting battles by sea and land… I want you all now to help me to send a Christmas present from the whole nation to every sailor afloat and early soldier at the front…. Could there be anything more likely to hearten them in their struggle than a present received straight from home on Christmas Day?

The effect of the letter was electric – achieving half of the required funds by the end of the month – but what was the motivation behind it?

The first meeting

Emerging from the princess’s sparse prose (recorded in her personal diary, now preserved at Harewood House)) is the revelation that the gift’s origins lay in a pivotal meeting at Buckingham Palace on October 8, 1914. The meeting – with Queen Mary, the Prince of Wales (otherwise known as Prince Edward: the man who would become Edward VIII and later abdicate the throne) and the prince’s treasurer, Walter Peacock – was held to “arrange a fund” to “send pipes and tobacco to the sailors and soldiers”. Such a matter-of-fact diary entry for what would become such a huge undertaking.

As revealed by historian Peter Grant in his study of charitable schemes in the war, Queen Mary had, from the outset, promoted her eldest son as head of the National Relief Fund – a charity set up in August 1914 to support families and ex-servicemen made destitute by war. It was highly successful. There can be no question that the Queen was steering her children to take their place in the war and finding a role for her daughter was equally significant.

But why a Christmas gift? In 1899, in the first year of the Boer War, Queen Victoria had set about providing a uniquely personal present to the soldiers then fighting in South Africa. The Queen’s gift – of chocolate in a specially commissioned tin – was set to become one of the most treasured artefacts of the war, and had a positive impact on Mary.

While the Queen paid for this gift herself, there was no possibility that Mary could fund her own version, and a call to the public was needed, taking the scheme from a purely personal royal act, to a national campaign during a traumatic year of war which had seen defeats on the battlefields and losses on the high seas. But the parallels with Queen Victoria’s morale-boosting gift of chocolate to the troops could not be clearer.

The appeal was launched on October 14 – just six days after Mary’s initial meeting and barely two months before Christmas. Its General Committee was composed of 38 prominent citizens (13 of them women) while delivery of the gift was managed through a smaller executive committee. Established at the Ritz Hotel, in London’s Mayfair, nine influential people determined the future direction of the fund.

This meeting was chaired by the Duke of Devonshire and attended by principal officers Walter Peacock, publisher and advertising executive Hedley Le Bas, and the secretary Rowland Berkeley. The other members listed on the committee papers were: H.V. Higgins, Capt Foley Lambert RN, General S.S. Long, Lady Florence Jellicoe and The Hon. W. Lawson.

The initial number of recipients was estimated to be about 145,000 sailors and 350,000 soldiers, meaning that at least 495,000 gifts would be needed. But the gift fund would eventually assemble around 11 million objects, gathered together to make up the 2.6 million gifts that were distributed worldwide by the end of the war.

A global campaign

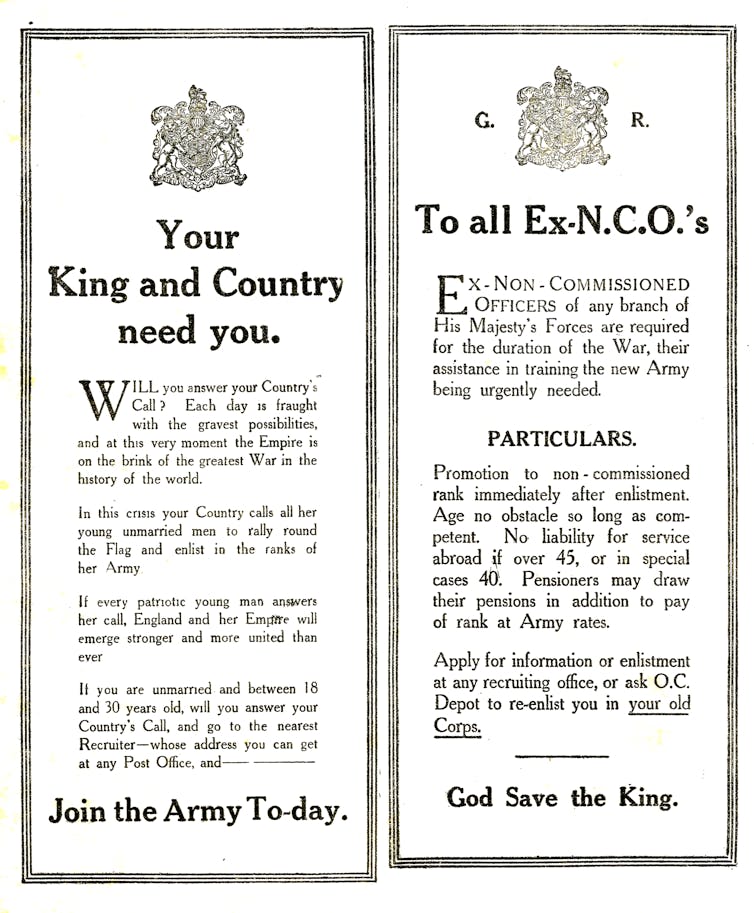

Funding this huge undertaking required advanced techniques, and Le Bas was the person to do it. According to research by historian Nicholas Hiley, Le Bas convinced the British government in 1914 “of the advantage to be gained from domestic propaganda” and created the “Your Country Needs You” recruitment campaign that built Kitchener’s army.

Not surprisingly, Le Bas took a significant part in the gift fund, deploying the princess’s touching letter to great effect. Applications for money were made through a direct appeal to prominent citizens, landed gentry and relevant highly placed groups.

And with its emphasis on Christmas and the youth of the Princess, it was expected that the fund would have a special resonance with young people, who – according to an article in the Montrose Standard on October 30 – “knew the enjoyment of home, and who appreciated the happiness of Christmas gifts”. School children were especially targeted as providers of “coppers” by local fundraisers and schools ultimately raised more than £6,000 for the fund.

Throughout October and November, money flooded in from all sections of society. And public generosity was not restricted to Great Britain, but came from across the Empire, particularly Canada. In Winnipeg, Manitoba, locals “gave a patriotic tea”, the proceeds of which went to the fund. As reported in the local newspaper, the Winnipeg Tribune, on December 4:

The reception room and the dining room were aglow with red, white and blue lights. The tea table was centred with a battleship, around which were smaller ships, with tiny soldiers and flags surrounding them.

Aided by Le Bas’s advertising acumen, the weekly rise in donations soon went beyond the expectations of the executive committee. By the end of November, the chairman announced that as “the public are responding so generously Princess Mary’s fund for sending Christmas gifts to all sailors afloat and all soldiers on the front that her Royal Highness has decided to extend it sending a present to all the British, colonial, and Indian troops serving outside the British Isles”.

This decision would have major ramifications.

An enormous task

It was now down to the executive committee to actually deliver. They had to create a suitable gift which could be made and distributed in time – a task that was frankly quite enormous. Its centrepiece was the intricately designed brass box reflecting the Edwardian taste in design. Central to the box was a representation of the princess herself, depicted in profile, and surrounded by a laurel wreath. The design was heralded in the press, a gift worthy of those serving at sea, or at the front. Yet there were challenges in rendering this in brass.

On November 17, the executive committee was informed that the secretary, Rowland Berkeley, had entered into contracts with three prominent box manufacturers. Each was contracted to produce 166,000 brass boxes at a net cost of just over six pence each. This amounted to (at this early stage) 498,000 boxes at a cost of just over £12,968. But the box manufacturers’ usual business was making boxes out of tin-plate. Finding a supply of brass would be an entirely different matter and the manufacturers could not foresee how hard it was going to be to source the brass they needed.

That’s because brass was a significant alloy used in a variety of munitions, with its primary components of copper and zinc also essential for that most vital process. With a shortage of shells on the horizon, there was little to be spared for endeavours peripheral to winning the war.

Given the insecurity of brass supply, Berkeley set out to obtain a reserve of brass to be controlled directly by the gift fund – an experiment that proved to be a failure. More brass would be needed and if that brass could not be sourced from home foundries then it would have to be sought elsewhere, particularly in America.

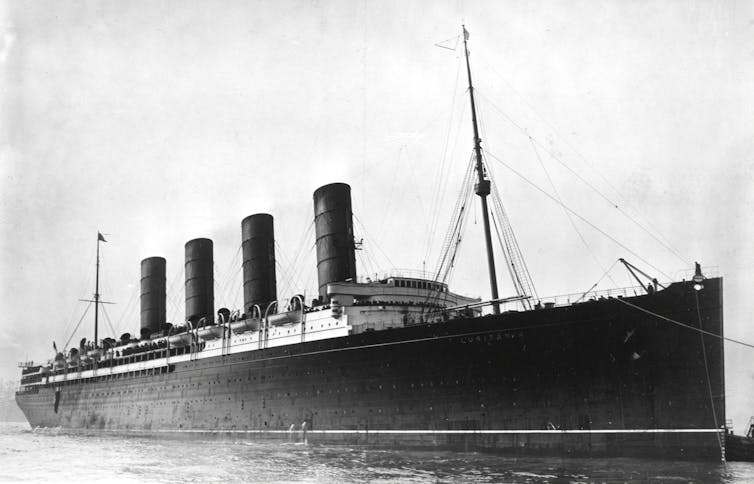

This would be a difficult proposition, as later in the war, supplies set aside for the gift boxes would be “sent to the bottom of the Irish Sea”, part of the cargo of the ill-fated liner Lusitania, which was torpedoed with great loss of life on May 7, 1915.

What was in the box?

On November 26, the Manchester Evening News reported on the gift’s progress. “The present consists of an embossed brass box, tinder lighter, a pipe, cigarettes and tobacco, with various alternatives for non-smokers, together with a Christmas card,” the report states.

The story continues, saying 500,000 boxes have been ordered and are now being made in “four important centres of industry” in Great Britain. Three manufacturers were supplying the tinder lighters; tobacco was being supplied by three other firms; cigarettes by two, and pipes seven. The covers for the packets of cigarettes and tobacco were being printed by a London firm. The orders for the Christmas cards and the cardboard boxes for packing the present were also placed in London.

One of the first issues was the tinder lighter. Supplied by the high-end silversmiths, Aspreys, it would founder on the basis that the “ceric stones” needed to ignite the lighter would have to be sourced from Austria – an enemy state.

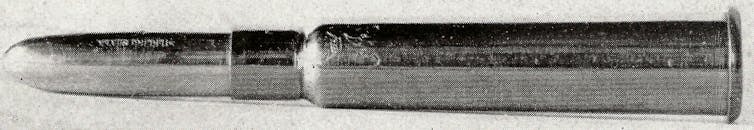

In a hurry, off-the-shelf replacements were sought by Berkeley. But for one member of the executive committee, dedicated to upholding the status of her husband’s navy, this was not good enough. Lady Jellicoe (who was married to Lord John Jellicoe, Admiral of the Fleet) insisted that naval personnel should receive a specially commissioned “bullet pencil case”, consisting of a bullet cartridge and a silver pencil holder. And this would not be the last time that Lady Jellicoe made her presence felt in the committee.

Non-smokers

So the navy got special treatment, but it may come as a surprise to learn just how much thought went into catering for non-smokers, too. At the time, 96% of soldiers smoked so the choice of sending pipes and tobacco made sense. But one matter that had clearly influenced the executive committee was the fact that for Sikhs, “the smoking of tobacco was strictly forbidden”.

With this in mind, and in order to ensure that the needs of the Indian Corps were met, the executive committee consulted widely with experts who knew India and the Indian soldier best. As early as October 15, the committee determined that the Indian Corps should have “sweet-meats instead of tobacco and cigarettes”. In the end, four different variants of the gift were devised and distributed to Indian troops.

This effort gained more poignancy in 2014 when just north of the Belgian city of Ypres – where in 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres, British forces lost 59,000 men – a short section of trench in a piece of formerly devastated landscape was found by a small team of archaeologists. Alongside the detritus of war were the sad remains of men – men who had fought and fallen in these battlefields; men whose names were recorded on memorials to the missing, but whose graves were no more, lost for a century.

Identifying fallen soldiers recovered from the battlefields of Flanders is notoriously difficult, as identifying marks and tags are easily lost with time. Both of these men found in 2014 wore uniforms of the British Army, but details of their equipment, and the fact that one at least carried distinctive Indian “One Anna” coins, dated 1914, in his pocket, indicate that they were probably Indian.

Both soldiers were most likely killed during the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 and both carried the revered gift from the princess in their breast pockets. It is hoped that this may provide some measure of identification for these men.

But there were other minority groups and the minutes of the executive committee indicate that there was a vocal pressure group that reacted unfavourably to announcements of tobacco.

Perhaps associated with religious abstinence that was at the root of Victorian–Edwardian anti-smoking campaigns, this lobby influenced the committee such that it decided unanimously that “non-smokers should receive boxes of sweets, or chocolates, instead of pipes, tinder lighters, and tobacco”. Eventually it was decided that a box containing “acid tablets” (citrus sweets) and a handsome pack of writing materials would be distributed to non-smokers, at a proportion of two such gifts to 56 standard ones.

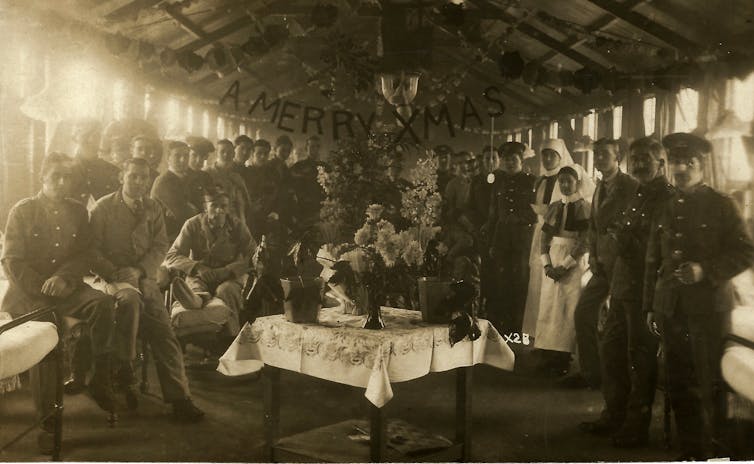

Forgotten nurses

But while non-smokers’ needs were considered, there were other potential recipients deserving of a dedicated gift, too. The British Army in Flanders, the British Expeditionary Force – and the Indian army that fought alongside it – did not solely consist of male soldiers. There were also female nurses, members of the Army Medical Service, who served close to the front alongside the doctors and orderlies of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Surely their efforts and sacrifices should also have been recognised?

Surprisingly, despite their dedication to duty, the first mention of gifts for nurses was at the executive committee on October 27 – some two weeks after the launch of the fund. Evidently, nurses had not been considered from the outset – a surprising oversight.

But my research suggests that this was indeed the case, with the nurses seemingly an afterthought. Their gift was only confirmed on November 24 at a meeting that announced the increased income of the gift fund. The 1,500 nurses eligible received only the box and chocolate. It was well received but it seems to be such a small gift for such gallant conduct. One nurse, serving on an ambulance train at Ypres, described the conditions that surrounded the issue of the gift.

Saw my lambs off the train before breakfast. One man in the Warwicks had twelve years’ service, a wife and two children, but ‘when Kitchener wanted more men’ he re-joined. This week he got an explosive bullet through his arm, smashing it to rags above the elbow… We had Princess Mary’s nice brass box this morning…Sister Kate Luard, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service

To the end

With Christmas 1914 over, the vast majority of the gifts had been delivered to the men in France and Flanders, and though men of the Royal Navy on far stations would have to wait, they had every expectation they would receive their gift in due time.

That the box and its contents were well received by their recipients cannot be in doubt. Some would even have occasion to thank the princess for saving their lives.

I have had a very lucky escape from being wounded. I was walking behind another fellow when a bullet came straight through his leg, and I felt it strike me. I looked and found it had gone through my overcoat and pocket, and the Princess Mary box was dented, and I found the bullet in my pocket. It had struck it sideways somehow, and it had turned it. Private Harry Towers, Lincolnshire Regiment

But the decision of the committee to extend the gift to every man in the King’s uniform on Christmas Day meant that an additional two million brass boxes would have to be produced, together with contents that were now reduced to the “bullet pencil cases” that had been first devised by Lady Jellicoe.

Fully dependent on the supply of brass, these gifts, sent across the Empire, would start arriving in 1915 to be distributed in parades and at depots, often, with extra poignancy, to the families of soldiers who had lost their lives in the war. One Australian wrote to local newspaper The Broadford Courier on December 21, 1917, in order to acknowledge just how important the gift was to them.

A very nice Xmas box has just come into the possession of Mr and Mrs. R. Ross of this town. In the Xmas of 1914 Princess Mary presented each soldier of the AIF abroad with a present, and it fell to the lot of their son Peter (killed in action at Gallipoli) to be one of the many to receive a gift. It is a very handsome box, artistically finished in many designs, a cartridge turned into a pencil case, and a Xmas card. Needless to say, Mr. and Mrs. Ross highly prize Princess Mary’s gift which… is now become one of their treasured possessions to be kept in memory of the brave sacrifice of their son.

Distribution of the gift would not cease until 1920, when the burden of responsibility fell to Army Depots. The huge effort that had been expended in delivering the gift over six years took its toll, and there was never any chance that this moment of hope would be repeated in the years that came after. There was just too much at stake, too many other deserving funds, too great a need for materials to prosecute the war.

Nevertheless, it was not forgotten. In 2014 – 100 years later – the famous London firm of Fortnum & Mason contrived to supply its own commemorative gift in the spirit of the Princess Mary Tin to all service personnel on deployment at Christmas.

And so, over 100 years later, this modest gift has left a legacy of care and respect for those who serve and are separated from their families and loved ones at Christmas. All those years ago, a 17-year-old princess understood that – and decided to make a difference. She achieved her aim, and the act, and her kindness, has never been forgotten.

For you: more from our Insights series:

- WitchTok: the rise of the occult on social media has eerie parallels with the 16th century

- The Prestige: the real-life warring Victorian magicians who inspired the film

- ‘We have nothing left’ – the catastrophic consequences of criminalising livelihoods in west Africa

Peter Doyle, Professor and Head of the Research Office, London South Bank University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.