Table of Contents

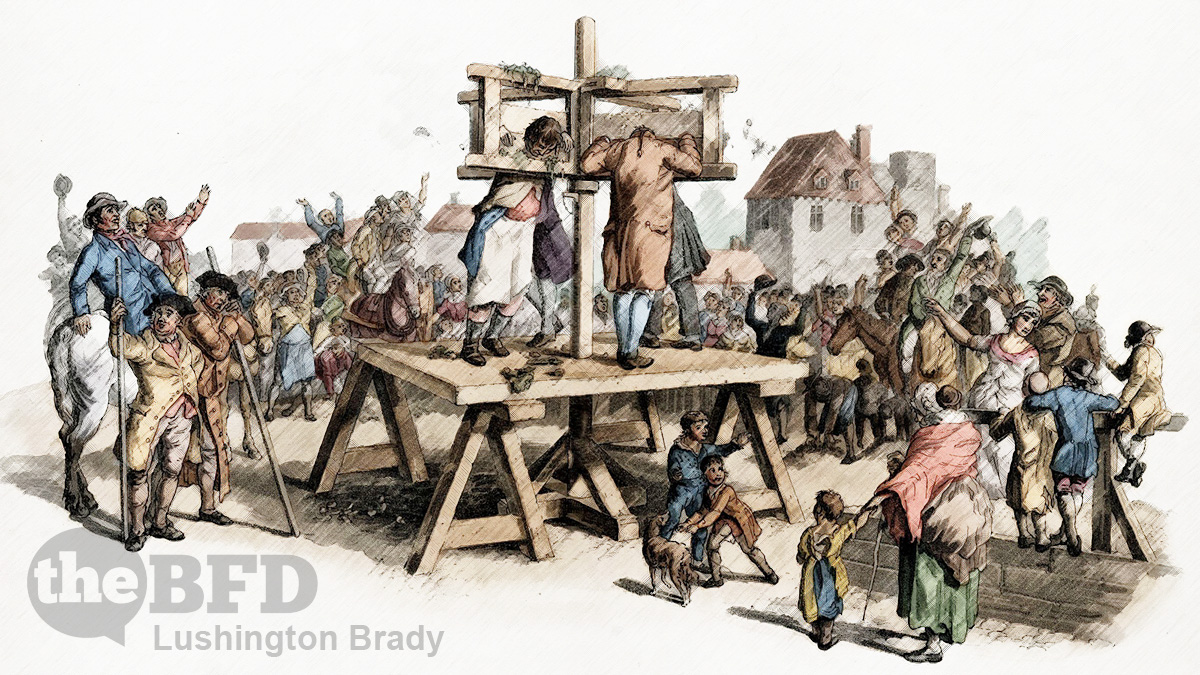

In a sleepy little town here in Northern Tasmania, tucked away in a quiet corner of a local park, is a grim reminder of a not-so-distant past: the village stocks. They’re now something for tourists to pose for happy snaps in, but once upon a time they were a very part of a practice that rightly came to be regarded as barbaric: public shaming.

Yet we now see our society sliding wholesale back into the sort of barbarity we fought so hard to put behind us. The means might be different – no one is physically placed in stocks any more – but the process is the same: mob rule and brutal public shaming, in lieu of justice.

As extremely serious accusations proliferate about behaviour by senior politicians that is claimed to have occurred years or even decades ago, the greatest damage is likely to be to the cause of justice itself. To say that is not to contend that the allegations, which have been strenuously denied, are necessarily ill-founded. But there are good reasons the Athenians, whose legal system allowed any citizen to act as a prosecutor and press claims on behalf of alleged victims, introduced a five-year limit on the time that could elapse between when crimes (other than murder) allegedly occurred and when an accusation was launched.

As the Greeks realised, great harm was done, not just to individuals, but to the polity as a whole, by what they called borborotarax. The Greeks saw that malicious and unscrupulous individuals exploited rumour and innuendo to enrich themselves and bring down opponents. Hence, they were dubbed borborotarax, “stirrers of muck or excrement”.

Characterised, according to Aristotle, by rancour, slander and malice, the [borborotarax] relied on digging up old claims, which were inevitably hard to disprove, and then used the pretence of assisting a victim’s search for justice as an excuse for their defamatory attacks.

Over the next thousand years, Greek ideas of law and governance collided with Germanic tribal law, which focussed on vengeance and restitution for wrongs. Christian scholars such as Anselm and Aquinas urged a kind of synthesis: giving victims their due, but also recognising that justice was a public responsibility, as lawlessness harmed not just individuals but societies as a whole.

The importance of timely justice became even more imperative during the reign of absolute monarchies in the 18th century.

It was precisely so as to prevent those abuses, and protect the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial enshrined in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, that the French liberals who drafted the criminal code of 1791 gave new life to the Athenian statutes of limitation.

The Terror instituted by the Jacobins – direct ancestors of today’s left – might have briefly swept aside such notions of justice and due process, but the idea refused to die. The Napoleonic code restored such ideas as the statute of limitations.

“Civil peace cannot persist if claims for vengeance are allowed to remain eternally armed and active, hanging over social life,” Pierre-Florent Louvet explained, in presenting the draft provisions to parliament; “instead, wisdom requires that the passage of time should lead society to remove legal culpability from events (whose contours) have blurred into the distant past.”

In place of such eloquence and reason, what we have today is ignorant frightbats screeching that “women never lie about rape”, in plain defiance of not just reason but objective fact.

Now those convictions have all but disappeared. And what has filled the vacuum is a renewed culture of retribution, in which those who rightly or wrongly define themselves as victims assert a moral right to be vindicated, quite regardless of whether they have respected their own moral obligation to assist, where they reasonably could, in justice’s timely pursuit.

Aided and abetted by a media that, while claiming to act in the public interest, repeatedly ignores the fundamental Roman axiom of justice — Audi alteram partem, hear the other side — public shaming is replacing the judicial establishment of guilt. And with these contemporary sycophants leading the search for charges that can neither be proven nor rebutted, politically motivated scavenging through the detritus of the past is overshadowing the impartial ascertainment of legally actionable facts.

As Franz Kafka characterised it in The Trial, such delving in excrement does not lead to justice, but endless persecution.

An ambush perpetually waiting to happen, a disease from which there may be temporary remission but no cure, a nightmare weighing even more heavily on the entirely innocent than on the irretrievably guilty.

The Australian

The modern borborotarax self-righteously pose as “progressive”. In reality, they are unforgivably atavistic.

The ancient Athenians would have recognised the state that the left are dragging justice to. They even had a name for it: Barbarism.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD