Table of Contents

Graham Adams

Graham Adams is a freelance editor, journalist and columnist. He lives on Auckland’s North Shore.

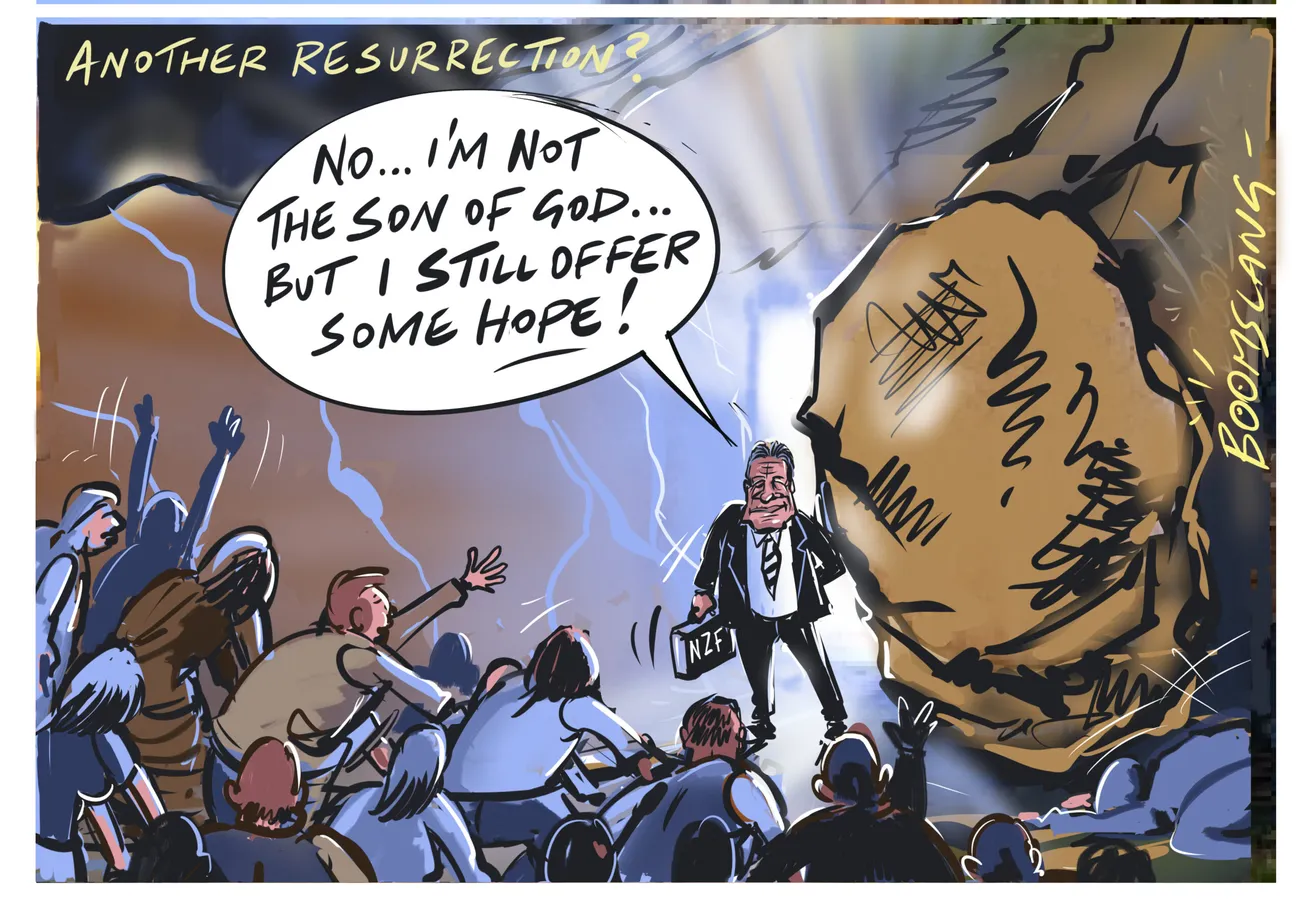

Even the PM is not convinced NZ First will shun Labour.

In November last year, the NZ Herald’s senior political correspondent Audrey Young broke the news that “For the first time since MMP began, the former Deputy Prime Minister and New Zealand First leader [Winston Peters] has emphatically ruled out working with a major party.”

Young reported that a reason for Peters’ assertion that he wouldn’t be part of a Labour-led government after this year’s election was because he had been “kept in the dark over the commissioning of He Puapua and what the Three Waters reforms looked like”, which he described as a “secret agenda”.

“No one gets to lie to me twice,” Peters said. “We are not going to go with the Labour Party, this present Labour Party crowd, because they can’t be trusted. You don’t get a second time to lie to me, or my party — and they did.”

You’d have to say Peters’ stop-the-presses announcement in November hasn’t aged well given the persistent questions about his own trustworthiness as the election looms.

First, it appears Peters was actually part of the Cabinet committee that approved the development of the report that became He Puapua and, second, even the Prime Minister is not convinced the veteran politician won’t form a government with Labour after the election.

In March, Newshub’s Amelia Wade decided to look more closely at Peters’ claim about He Puapua. She discovered that he — and Shane Jones — had actually been at the March 2019 Cabinet subcommittee that agreed “to develop a national plan of action” to respond to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, known as UNDRIP. That “plan of action” became the contentious He Puapua report, which outlined a roadmap to achieve comprehensive co-governance in New Zealand by 2040.

Wade then set a televised trap — indeed, one worthy of the “old crocodile” himself, as Simon Bridges colourfully described NZ First’s leader in his memoir.

Wade: “You had nothing to do with the work on UNDRIP?”

Peters: “Of course, I didn’t.”

Wade: “Weren’t you in the Cabinet committee that signed it off?”

Peters: “Totally false.”

Unfortunately for Peters, Wade had the Cabinet paper on hand and had already flashed it up on screen to prime viewers before the trap snapped shut. There at the top of the list of attendees was the “Rt Hon Winston Peters”.

At 78, and only two years younger than the well-known amnesiac Joe Biden, Peters could perhaps be forgiven a senior moment. As Act’s deputy leader, Brooke van Velden, put it: “The fact he says he didn’t know about it either says he completely forgot that he signed it off or he can’t be trusted.”

Certainly, whether Peters can be trusted is a question that is following him everywhere in this election campaign.

Commenters often see a gap between what he promises on the campaign trail and what he does once he is in government — and one that can’t always be easily explained by the demands of negotiating a coalition agreement with one of the major parties.

In 2017’s campaign, he promised to “drastically reduce” net immigration from 70,000 a year to 10,000. Given his long history of beating an anti-immigration drum — including describing National’s “mass immigration” policy as “economic treason” — it was widely believed his party was truly committed to slashing numbers.

Similarly, Jacinda Ardern — acknowledging the pressure on infrastructure and housing – strongly implied Labour would reduce net migration by 20,000-30,000 people a year.

Astonishingly – and devastatingly for those who voted for Labour or NZ First largely because of these pledges — their coalition agreement said only that the parties’ “shared priorities” would “Ensure work visas issued reflect genuine skills shortages and cut down on low-quality international education courses” and “Take serious action on migrant exploitation, particularly of international students”.

“We lost the argument,” was Peters’ breezy summation. This baffled those who believed that, because the two parties had publicly committed to significantly cutting net immigration, Peters would be pushing on an open door.

Furthermore, to the fury of his supporters, in December 2018 as Foreign Minister, he cast his vote at the United Nations to sign up New Zealand to the Global Migration Compact, which critics said could restrict New Zealand’s ability to set its own migration and foreign policy.

Peters does, of course, win concessions for his supporters in coalition agreements — with some nominating the Gold Card, which gifts pensioners free public transport, as his most enduring legacy over his four decades in politics. He also reliably secures plum jobs for himself. In 2017, with 7.2 per cent of the vote, he became Deputy Prime Minister, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Racing.

It seems, however, as if his history may be catching up with him this election season. Questions about his trustworthiness are a regular feature of comments on tweets he posts. Some are from supporters who have not forgiven him for going into a coalition with Labour in 2017. And they are not convinced that he won’t do it again, despite his promise repeated in late June: “No, we are not going into coalition with Labour.”

One Twitter comment said: “How can we vote for you? We need Labour and its hangers-on out before New Zealand disappears completely. You would go with Labour again. History is a great teacher and this is what you have [done] and will continue to do.”

Such criticisms are so persistent that Peters has little choice but to address them. Shortly before the party’s campaign launch at Auckland’s Mt Smart Stadium last week, he admitted questions about the 2017 election “need to be answered” — and that he was asked similar questions following the first MMP election in 1996 when NZ First went into coalition with National.

In 1996, very few people — including journalists — expected Peters to form an alliance with National’s Jim Bolger. As Danyl McLauchlan wrote in an essay for The Spinoff titled “The Boxer and the Towel”:

“In the October 1996 election, New Zealand First won 13.3 per cent of the [party] vote, and all of the Maori seats, capturing them off Labour for the first time in history. During the campaign Peters strongly implied that he’d form a government with Labour, instructing voters to ‘put Jim Bolger in opposition where he belongs’. But, it turned out, Peters had not actually promised that he’d form a coalition with Labour, at least not in so many words, and after two months of negotiations — some of which Peters famously spent on a fishing holiday — he formed a government with National.

The media literally gasped with shock when Peters made this announcement, and Peters walked off without taking any questions.”

It wasn’t just Labour supporters he massively disappointed. In the weeks that NZ First was negotiating with National and Labour, Dr Ann Sullivan, a Maori political scientist from Waikato University, told TVNZ’s Marae that only five per cent of the total Maori vote had gone to National. “They do not want to see Winston Peters go with the National Party… I think it would put Winston in a difficult position if he was to align with the National Party because Maori clearly do not want National.”

But National is what his Maori supporters got.

McLauchlan: “The decision devastated his popularity. In the first public poll after the government was formed he was down to four per cent in the preferred Prime Minister ratings and he never regained his earlier popularity. On the other hand, Peters was now Deputy Prime Minister and ‘Treasurer’, a new position created to ensure that he outranked the Finance Minister, normally considered the second-most-powerful member of Cabinet.”

In 2005, Peters also signalled before the election he would not go into government with either National or Labour, and vowed he would eschew the “baubles of office”.

The election saw Peters lose his seat of Tauranga but NZ First managed to scrape into Parliament with 5.72 per cent of the vote. Despite his pledge, Peters accepted the “baubles of office” by becoming Helen Clark’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister for Racing.

It’s easy to see why even Chris Hipkins is not convinced that Peters will keep his word this year either. At a post-Cabinet press conference in mid-May, journalists asked the Prime Minister about Peters’ claim he would not go with Labour.

Hipkins replied: “Winston Peters has ruled people out before only to work with them after an election. Ultimately, it’s really a question for New Zealand First.”

Media: “So you could work with Winston Peters? You’ve got a good relationship?”

Hipkins: “I’ve indicated that we’re not going to be making those calls until closer to the election.”

Some of Peters’ followers are making much of the fact that this is the first time he has so emphatically ruled out working with either of the major parties before an election. However, when even the Prime Minister doesn’t believe him, putting store by that particular promise requires a great deal of blind faith and optimism.

Nevertheless, even critics have to admire his chutzpah and deadpan sense of humour — which is on full display in his campaign video released last week. For many, the standout, thigh-slapping moment will be when he speaks directly to camera and says: “We speak for New Zealanders like you… who feel betrayed by the people you may have voted for in the past.”

This article was published at The Platform