Table of Contents

Decades ago, notorious Kiwi-Australian journalist Derryn Hinch observed that con-men tend to make money off people who are just stupid and greedy. That was true enough in the pre-digital ’80s and ’90s, when the stock-in-trade of con-artists was get-rich-quick schemes.

Today, though, that’s all changed. Scammers make money because people are trusting and technologically naive. Which is not the same as ‘stupid’ – very far from it. Spotting modern scammers takes a certain skillset. Skills, unfortunately, that many of us aren’t routinely taught.

Which is how totally innocent people like Katherine Corry are conned by unscrupulous, disgusting online scammers.

A five-minute phone call left Katherine Corry’s bank account drained of money she had put aside for her son’s funeral.

What happened to Corry is a valuable lesson in just how cunning scammers can be.

On September 26 Corry was sent a text message saying there was suspicious activity in her Kiwibank account.

She opened the text and then received a phone call from a male scammer impersonating a Kiwibank worker.

Corry said he accurately listed a series of past transactions she had made and told her he was inside her account.

“I told him [the scammer] I’ve been sick and my son who lived with me has just recently died, so I’m a bit all over the place.”

No decent person would exploit such obvious vulnerability. Scammers are not decent people.

He convinced Corry to tell him the unique code she had set up with Kiwibank, and then said he would place her on hold.

Corry sat down to have dinner and when she re-checked the phone the line had gone dead. She opened up her bank account and saw $9900 had been withdrawn.

“I couldn’t speak, I just said to Ken [Corry’s brother-in-law] ‘It’s gone, my money’s gone’.” […]

Corry had already spent $45,000 on treatment for her son who died of bowel cancer in July, and part of the $9900 stolen from her in the scam was intended for his funeral.

“It was just horror and feeling so stupid.”

Stupid is something she should not feel. Nor guilt. These bastards are as cunning as they are unscrupulous.

Corry was let down by her own bank, as well.

Corry contacted Kiwibank immediately after the scam and was told her account would be frozen for 15 days and then she’d be contacted by the bank.

But when that failed to happen, she was told by staff that the fraud investigation team was currently “snowed under”.

Corry’s daughter Sue Taylor said she couldn’t understand how the withdrawal wasn’t flagged by Kiwibank as being suspicious, considering the large sum of money was made under a foreign name to an offshore account.

“The scam transaction sticks out by a mile all of her transactions are local and small.”

In my own experience, even the smallest transactions can trigger an alert at a bank. When I bought an e-book (about $4) from a small, independent online publisher, my bank phoned me within less than 10 minutes to check on the transaction.

It took an inquiry from the media to goad Kiwibank into action, although, to their credit, they will reimburse Corry for the stolen money.

“I just want people to continue to be aware to be really, really careful.”

NZ Herald

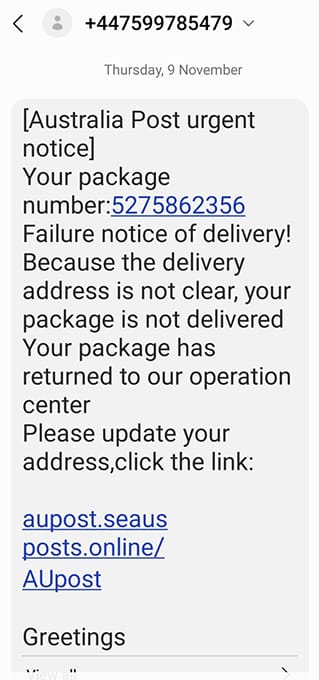

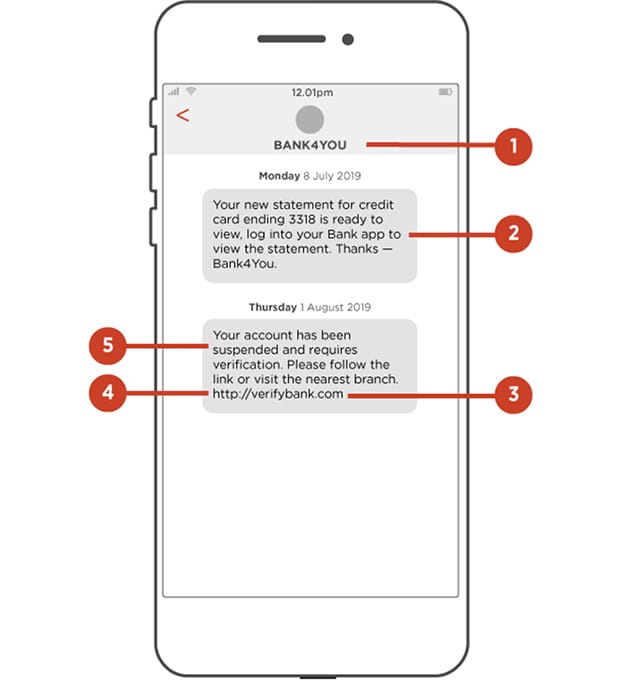

Katherine Corry has no call to feel stupid. Consider the text messages below — can you spot the legitimate versus the fake?

The header on the SMS looks real enough. Scammers can even hide behind genuine phone numbers or email addresses.

But note that the first SMS contains no links or phone numbers to call. It’s different in style from the second SMS. The previous SMS is legitimate and it provides information only. It tells you to log into your account but provides no links that could lead to potentially malicious websites.

The second, however, contains a link to click. NEVER click on a link purporting to be your bank. A real bank will never send you a link. ALWAYS go to their site or your app yourself, by typing their URL (internet address) directly into your browser’s address bar. Any messages you need to see will be available once you log in.

Note that the link in the scam SMS is not secure. Legitimate sites containing sensitive information will use https not http, but don’t rely on this alone – some scam sites use https, too. This is why you should always type the address of your bank into your browser yourself.

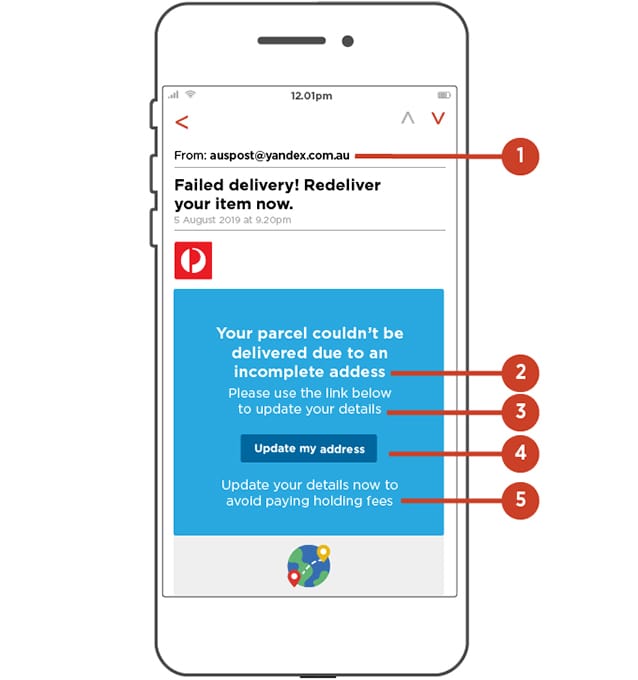

Another common ‘phishing’ scam (where scammers try to trick you into handing over sensitive information) is the ‘mail/parcel failed to deliver’ message.

As well, the scam SMS has a sense of urgency. Scams often try to create a sense of urgency. Don’t rush – take the time to think about what the message is telling you to do and consider whether it’s real.

Check that an email address of the sender is authentic. In this example, the domain name (the part of the email address after the @ symbol) is a sign that it’s not real. If you’re unsure, contact the business directly using contact details that you’ve sourced independently and you know are legitimate.

It has spelling and grammatical errors. These types of errors are a sign that it could be a scam.

You should also consider if your bank has the option for multi-factor identification. For instance, my banking app uses a combination of user number, password and fingerprint scanner. Others use unique number generators, which can be in the form of a physical key fob or a separate, secure app on your phone.

If your bank offers these – USE THEM.

Taking steps such as these are no guarantee, of course. Criminals are nothing if not devious. But some basic precautions could save you money and heartache.

Right on cue, just as I was finishing this post, I got a scam SMS: