Table of Contents

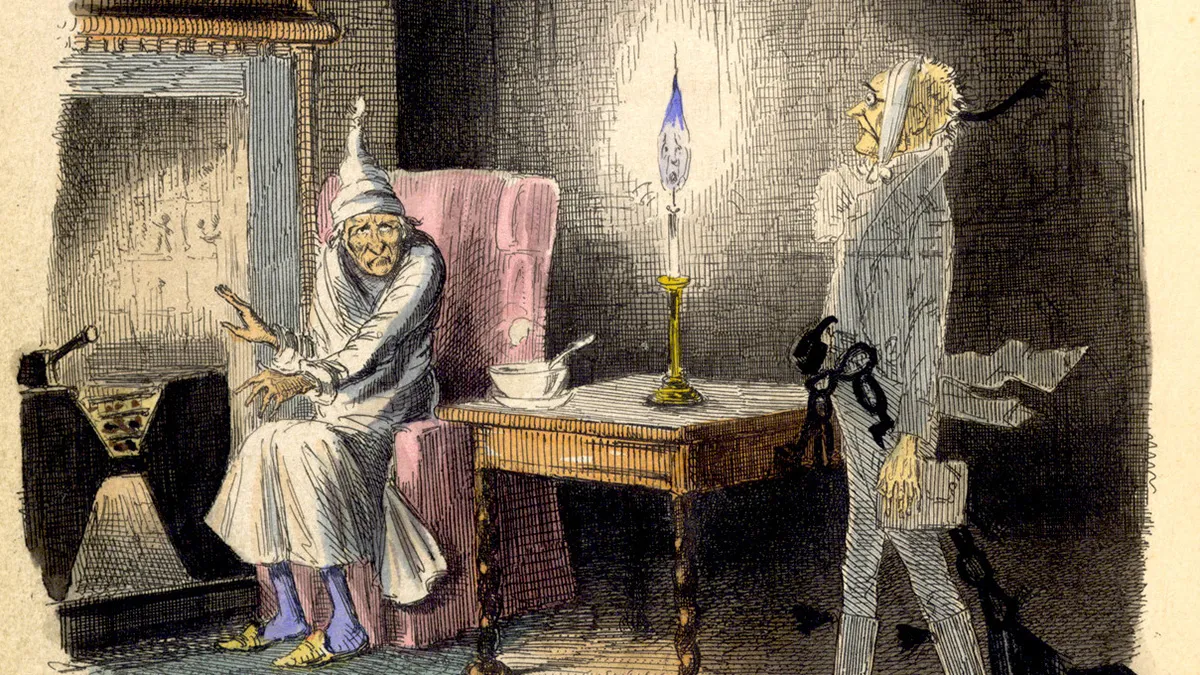

As one of The BFD’s Christmas posts noted, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is almost single-handedly responsible to establishing many of the features of our traditional Christmas. It also gifted the English language with a new pejorative: Scrooge. Derived from the story’s protagonist, Ebeneezer Scrooge, a “scrooge” has become a byword for a rich miser.

But, just as the post-modernists love to “re-evaluate” literary characters like Bertha Rochester, the mad wife of Jane Eyre and heroine of The Wide Sargasso Sea, is it time to re-evaluate Ebeneezer Scrooge? Is Scrooge a victim of the bourgeois socialist gaze?

Scrooge is a distilled caricature of a businessman in the Victorian era: a rich, obsessive wealth hoarder. Working in “his moldy old office”[…]he was “a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone.” He strove from dawn till dusk to “understand his own business,” and “with his banker’s-book” he trudged home in the dark “to take his gruel” alone by a dying fire.

Note that there is nothing actually unethical about Scrooge. He isn’t a cheat or fraudster, nor even particularly greedy. Just a dedicated capitalist. Like Karl Marx, living and writing in London at exactly the same time, Dickens fundamentally misunderstood capitalism.

Dickens, like Marx, and even more so Friedrich Engels who at least knew something of The Condition of the Working Class in England (if only because his wealthy family’s mills employed so many of them), was an observer of that stage of the Industrial Revolution when millions of formerly rural poor flooded into the cities. But, like Marx, Dickens was particularly myopic in his observations. The poor of the city slums were no poorer than they’d ever been – in fact, they were just beginning to be a lot better off – only more visible.

But what Dickens and Marx failed to realise was that this was only a passing phase of the Industrial Revolution. Far from suffering an “increasing misery”, the urban poor were about to experience a revolutionary growth in their material circumstances.

Thanks to the unloved Scrooges of the Industrial Revolution.

While the literature of the Victorian era paints a dark picture of mid-19th-century life in England, virtually every official measure of well-being shows the period from 1840-1900 to have been the beginning of a golden age for workers. Wages, stagnant for more than 600 years, exploded during the Victorian era—rising from less than $567 a year in 1840 to $1,216 in 1900 (expressed in 1970 dollars). Life expectancy rose by 20%. Literacy rates soared. As wages rose, the quantity and quality of nutrition improved dramatically, want diminished rapidly, and the mortality rate for Victorian children plummeted. Child labor, once necessary for survival, gave way to steadily rising school enrollment and made ignorance a dark memory. There had never been a comparable period of broad-based prosperity in all of recorded history—and, most amazingly, the progress has never ended.

Who then benefited from the accumulated wealth of Scrooge and Marley? First Britain and then all mankind. Since Scrooge and Marley never consumed the wealth they created, its use was a gift to all. It funded the factories and railroads, the tools and jobs that fed and clothed millions of British subjects and then billions around the world. Their unspent wealth was of no use to them, but it was of sublime use to humanity.

Yet, for all the fact that it was Scrooge’s dogged accumulation of wealth that fuelled the engine that dragged more people out of poverty than had ever been achieved in human history, Scrooge is not exactly an endearing character. This is the paradox of capitalism. Instead of accumulating his wealth, Dickens thinks – and indeed has – Scrooge give his wealth away in a great show of benevolence. Perhaps Dickens and Marx should have paid more attention to Adam Smith, who reminded us that “it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest”.

Scrooge’s wealth accumulation would have benefited far more people than anything he gave to charity after his reclamation, and many times more than government would have helped had they taken his wealth and spent it.

So on Christmas, as we celebrate the promise of human redemption and join in repeating Ebenezer Scrooge’s famous pledge, “I will honor Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all the year,” let us also remember the contributions that Scrooge and Marley and the wealth accumulators of our own age have made as “the founders of our feast.”

The Wall Street Journal

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD