Table of Contents

Misunderstandings are common enough in peacetime so it’s fully understandable that during times of war their frequency will be exacerbated and the contagion thereof more widespread.

The ‘Battle of Manners Street’, which occurred sometime around 79 years ago this month, was whispered of in my cohort’s youthful 1960s, the near-myth having some air of endurance, indeed permanence in local ears and, as late as last year newspaper and online articles have appeared and reappeared delving into the controversy, the cause and even the exact date, the incident not being reported in the contemporary times because of wartime censorship.

The event was real, very real, but, like all talk of wartime-doings, no actual combatants ever commented. However, scuttlebutt has appeal, stories must be told and embellished, about the Wellington (and possibly world)-famous ‘Maori vs Marines’ punch-up that went on for hours. Reportedly many non-Maori New Zealand servicemen and civilians joined the affray in support of their fellow Kiwis, although the exact dates and even separate events have become conflated in foggy reminiscence.

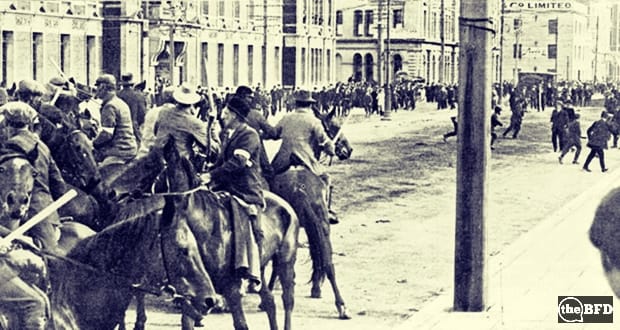

What common threads there are agree: both Maori and Marines were heavily involved, the brawl lasted in excess of two hours, four city blocks were cordoned off, civilian and military police combined were hopelessly unable to cope.

While there have been allegations, and slanders, of racial stereotyping on the part of the visitors from the USA as to the cause of the fracas, those particular defamations usually carry the rider of ‘uncertain’ or ‘unsure’ while, in the vacuum of facts, fib-tellers thrive.

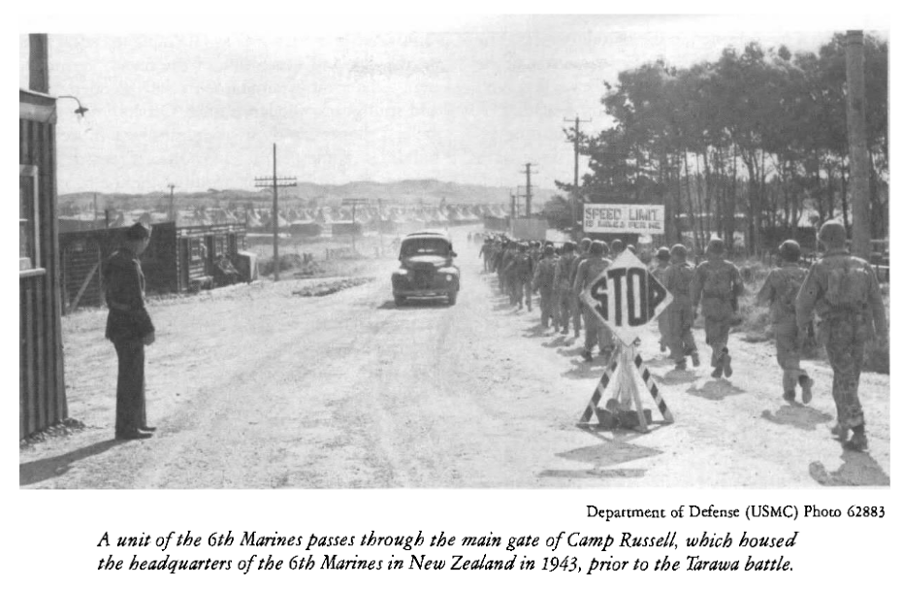

It’s important to have a little background: there had been other misunderstandings since the Americans’ arrival. Firstly at the waterfront with some of the heavily-unionised stevedores’ workforce ‘reluctant’ to assist in unloading military. In fact, a motion had been put to the Labour Party Conference fully two years before in 1941, by a group of “Pacifists and so-called ‘Communists'” in the party, to completely withdraw from the war (the motion was heavily defeated). The war effort by New Zealand and her allies was not universally supported in this country. The Marines didn’t mind; they simply unloaded themselves and packed the trains to Paekakariki, disembarking at their Camp Russell, next to McKay’s Crossing.

The Marines loved Wellington and Wellington the Marines, but still, misunderstandings endured. Who would have thought that verbal communication between two English-speaking countries could be so hard? The 6th Marines had previously been deployed in Iceland, alongside British units and had adopted “bloody” as a mild epithet:

“The Marines soon learned that it was a word not to be used in polite company in New Zealand. On their part, the [Wellington] girls learned not to use the word “screwed” as slang for “paid”.”

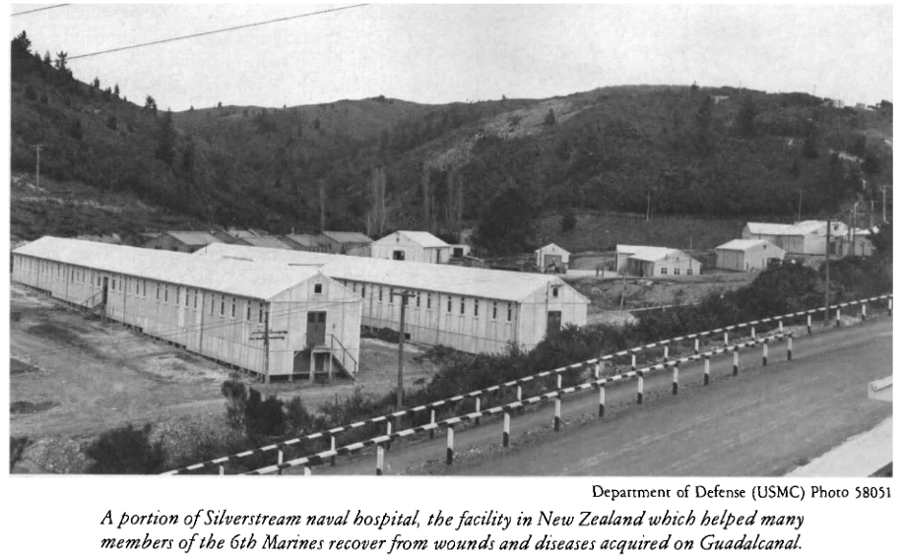

Dispatched to the Solomon Islands to fight at brutal Guadalcanal in late December 1942, 3000 fewer Marines would traipse the gangways to the waterfronts of Auckland and Wellington three short months later, while even larger numbers struggled to fight off persistent tropical diseases and infections. Many men were carried by train to facilities like the new US Navy Hospital hastily constructed at Silverstream.

In convalescing, the 6th Marines re-ignited their love affair with Wellington the city, if not the women they had known just fleeting weeks before, again due to a pure ‘misunderstanding’. Elements of the 2nd and 8th Marines had arrived in the city during the interval, eager to earn themselves a date with local girls reluctant to provide such company in view of the girls’ several and various promises to beaux among the absent 6th.

It seems the love rivals of 2nd and 8th Marines had assured the local ladies that the distinctive decorative braid worn on the 6th dress-uniform – the four-ragere – was not awarded for the regiment’s distinctive feats of bravery in France during the previous ‘Great’ war, but was in fact a sign the wearer had contracted venereal disease, a fib which nevertheless successfully swayed the resistance of several local lasses to taking a new hand in hers.

So how did servicemen, allies with a common aim and common enemies and common sense of humour, come to blows that autumn, 1943 evening? Lieutenant General William K Jones (retired) covered it in his A brief History of the 6th Marines in the most believable and complete commentary this writer has heard over the many years interval, and the many inventions:

“The movie theatres in Wellington were popular with the Marines, both those with and without dates. The movies ran on a set schedule, with intermissions between showings. At the beginning of each show, the lights dimmed, a picture of the King came on the screen, and the British national anthem was played. Everyone stood and remained standing. Then a picture of President Roosevelt was shown while the American national anthem was played. Everyone then took their seats and the movie started.

“During May, a Maori battalion, 400 strong, returned from more than three years in the war in the African theater. These Polynesian natives of New Zealand were known to be fierce fighters. One evening in one of the movie theaters the Maoris present stood for the British national anthem but sat down during the American one. The Marines demanded that they stand and show the same respect to the American anthem. The Maoris refused. A brawl resulted, which rapidly spread to the streets, with other Maoris and Marines joining the fight. Both American and New Zealand MPs were unable to break it up.

“With the approval of the Wellington Police, a four-square-block area of the downtown was closed off and the combatants allowed to fight it out. The injured from both sides staggered to the edges of the area, where military ambulances waited to take them to first-aid stations. There was no property destruction and very few serious injuries.

“From then on, however, the Maoris remained standing during the American anthem. The fight cleared the air.”

Just a misunderstanding about upstanding. That’s all.