Table of Contents

One of the hardest things to deal with when confined at home during an extended conflict or war is the abundant amount of forced free time one has on one’s hands.

Here I am a week into the conflict. With my place of employment closed, I find myself rising at 5.30 a.m., feeding the cat, making coffee, turning on the radio, reading the news and then I’ve got another 16 hours to kill before I put my head down at the end of the day.

The city is like a ghost town. Jerusalem is a town of one million souls, but since the beginning of the conflict, the streets have been all but deserted. Shops are closed, road traffic is slight and the deafening silence on the ground is punctuated only by the regular low-frequency rumble of F16s lining up for their bombing runs on Gaza. The residents are staying close to home, close to their safe rooms and bomb shelters, with uncertainty, concern and even fear of what will be. Ears are glued to the radio, in Hebrew, Arabic, and English.

It’s war: no parties, no fun family gatherings, no music. The children’s playgrounds are silent, the promenades and parks bereft of joggers, and walkers. The dogs aren’t getting a fair shake either, with walks cut short as soon as they have done their stuff. Blinds are drawn closed and people everywhere are inside, alone with their anxieties, their TVs, radios and endless time to kill.

The concept of ‘spare time’ is the paramount goal that all of us in the Western world strive towards our entire lives. Shortened work weeks, longer holidays, time in the sun, earlier retirement and so on, but when it is forced upon you suddenly and with the added uncertainty of being left pretty much in the dark, thinking you know something, but knowing you don’t…in short, forced ‘spare time’, due to sudden war, can be very, very laborious and dangerous to one’s health.

During the first week of the conflict we had already taken our curtains down, washed them and put them back up, dusted all of those difficult places one never reaches including the tops of the lampshades, stocked up our safe space with water, food, torches and medicines. One has to understand that trying to focus on relaxing pleasures, such as reading a good novel, creative writing or painting, are near impossible to enjoy. There is an underlying distraction that gnaws at your subconscious and you find yourself unintentionally tuning back in to that numbing war broadcast. Perhaps it will pass if the war draws on longer than expected.

Yesterday we decided we needed a breather from the unrelenting pressure of our solitude, the radio and our emotions. We headed on foot to the nearby park and Haas Promenade to pick olives for bottling. The public parks in Jerusalem have ample fruiting olive groves as part of their landscaping and it happens to be the olive-picking season. Usually, the olive trees and their free abundance are cleaned by families from local Palestinian Arab villages. This year, due to the tensions, they appear to be making much slower progress than usual.

The park was bereft of people: the only living thing besides us was a cheeky beige and red fox – something you don’t usually see in the middle of the day. He was probably there to enjoy the sudden absence of us bothersome humans.

We spent an hour looking for easy-to-reach low-hanging fruit, but in the end, I still had to climb a little despite my age and questionable agility. We managed to pick 4 kg of fat ripe Tsuri olives (origin in Tsur southern Lebanon) and headed home.

Pickling olives is an age-old annual pastime that Mediterranean and Middle Eastern folk have performed for thousands of years. Every extended family has its own secret recipes: this one belongs to my wife, Merav.

Ingredients:

- 3–4 kg of fresh olives

- 2 lemons

- 1 head of garlic, peeled

- Chilli peppers

- Bay leaves

- English peppercorns

- Thyme sprigs

- Coarse salt

- Water

- Olive oil

Method:

First, all the olives have to be cracked, crushed, incised…pick your torture. When an olive is pickled in salt it will shrink back onto its stone, leaving little or no flesh to enjoy. By separating slightly the stone from the flesh, the flesh retains its plump body

after being pickled.

Place all the cracked olives in a large container/bowl and add tap water until covered. Leave for 24 hours, drain and replace with fresh tap water. Leave to soak for an additional 24 hours, drain and they are now ready to pickle. This is done to remove the bitterness from the olives.

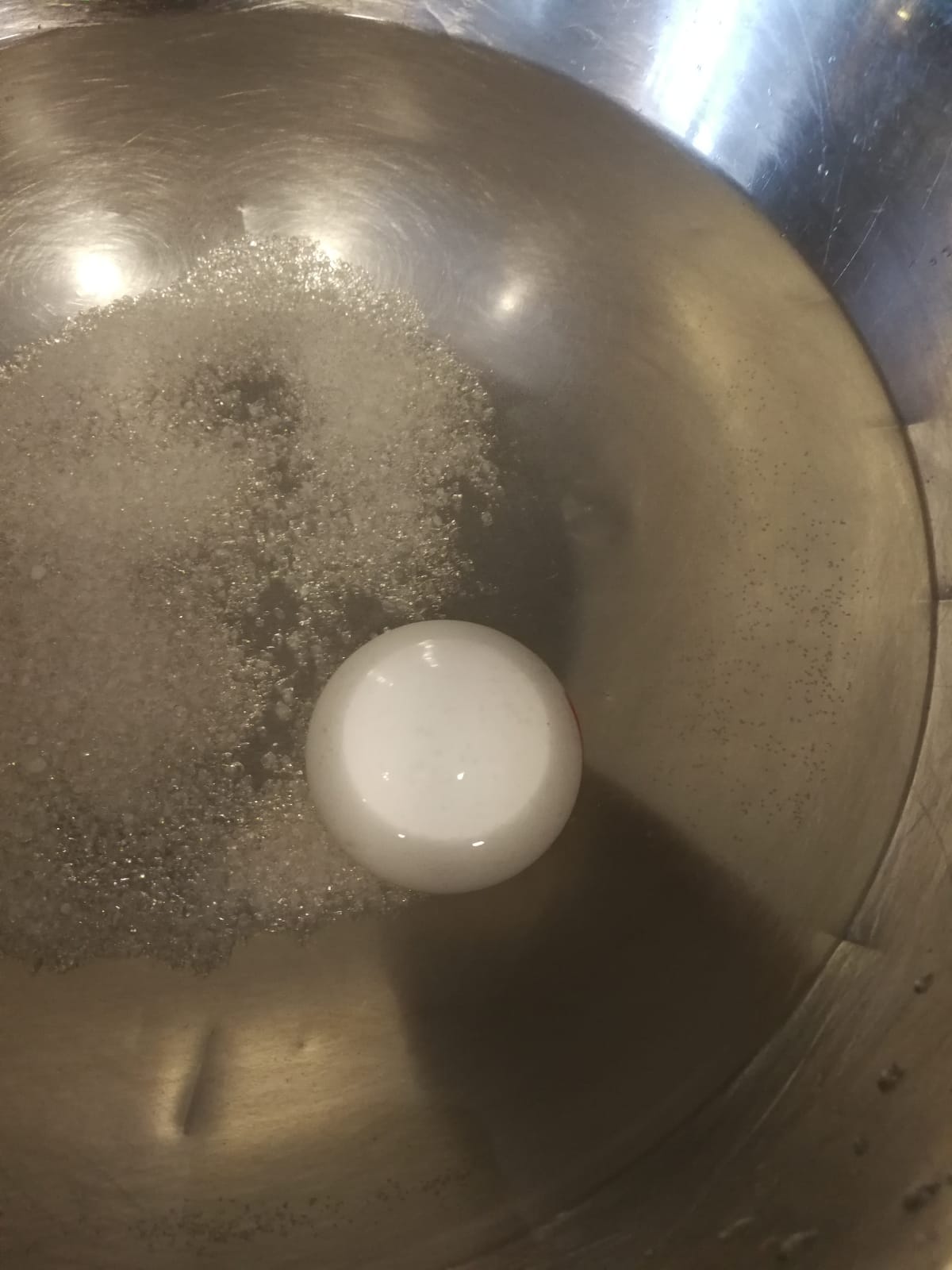

The most important part of pickling is achieving the right concentration of salinity. To do this, mix half a cup of boiling water with 2 tbsp of coarse salt, dissolving it completely in a bowl. Then start adding cold water: place a whole fresh egg in the water and keep adding water and salt in very small quantities until the egg floats.

Once you have the correct saline mixture, slice lemons, peel garlic cloves, grab some bay leaves and cut lengths of hot chilli pepper. Build the olives inside a jar, placing the herbs and flavours strategically as you go to give a nice aesthetic touch. Add 3 cloves of garlic per smaller jar, and 3 slices of lemon, 1 bay leaf, 3 English peppercorns, 1 sprig of thyme.

With all of your olives packed in jars, pour in the saline solution, making sure you leave 3–4 mm at the top for the olive oil to seal everything in. Close the lid tightly. Leave for at least 30–40 days before starting to enjoy.

If you enjoyed this recipe why not share it with your friends via social media or e-mail? If you want a copy of your own select the print option at the top of the page.