Table of Contents

Hongi Hika did not go to Britain just to work on a Maori dictionary. He went to learn about guns and to see the King. He tours the Tower of London (his favourite place), reviews soldiers and armaments, and meets King George IV who presents him with a suit of armour and many gifts.

When they return to Sydney, Hongi Hika trades all his gifts (except the suit of armour), for 500 muskets and gunpowder, returns to New Zealand, and leads his Bay of Islands Maori out against other tribes, including the tribe of the chief he went to Britain with.

When four chiefs from Thames meet Hongi Hika and want to go to Britain too, Hongi Hika tells them instead to “hasten home and prepare for war, I shall soon attack you”. And he does. He attacks the Thames Maori fortress at Totara for three days, and then when they make peace and he is invited inside the fort to trade, Hongi Hika’s Maori attack the Thames Maori at night, kill 1,000 of them, eat a lot of them, take 2,000 prisoners, and return north where the widows of those killed at Totara kill and eat the prisoners brought back for them in front of the missionaries (no need to say grace). Next up, the Auckland and Waikato Maori (1821).

Hongi Hika’s raiding party of 2,000 warriors and 1,000 muskets defeat the Auckland Maori at Tamaki and Panmure, almost wiping them out. They then go up the Tamaki River to Otahuhu, drag their canoes overland to Manukau Harbour, and reach the Waikato River to the south by taking more rivers and dragging their canoes over more land.

The Waikato Maori hear about the slaughter of the Thames and Auckland Maori, and take in the survivors. They build a strong defensive fortress at Tuakau protected by high river banks, ditches and palisades. When Hongi Hika’s canoes with 3,000 warriors arrive, some of the defenders rush out to attack them and are shot down by the muskets. The rest flee back into the narrow gateway into the fort where they are trapped and shot down from behind. Those inside the fort panic and try to escape and are also shot. Over 1,000 have been killed and hundreds more taken prisoner back to The Bay of Islands (1822).

Pushing farther south again, The Bay of Islands Maori defeat the Waikato Maori at Huiputea near Otorohanga, but are distracted by captured Waikato women and annihilated by a surprise Waikato night attack (1822). The Bay of Islands Maori and the Waikato Maori then make peace with a marriage between the two tribes and a wedding celebration that lasts two years. Some of The Bay of Islands Maori though move to the missionary station at Paihia so as to not be around if the Waikato Maori should one day come looking for revenge, which they do in 1827 (Maori revenge has no time limits and the Maori have a long memory).

Maori Battle Tactics

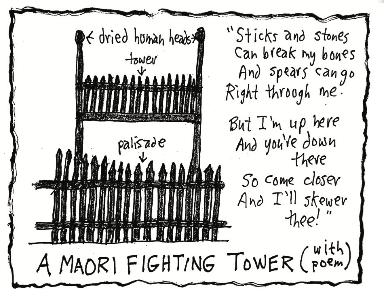

Before guns came to New Zealand, Maori battles were by hand-to-hand combat using clubs and spears. There was an opening exchange of ritual challenges followed by a general melee of warriors. The famous “Ka Mate” (‘Tis Death) haka performed by the New Zealand rugby team is a ritual challenge credited to being composed by Te Rauparaha, another famous Maori warrior chief.

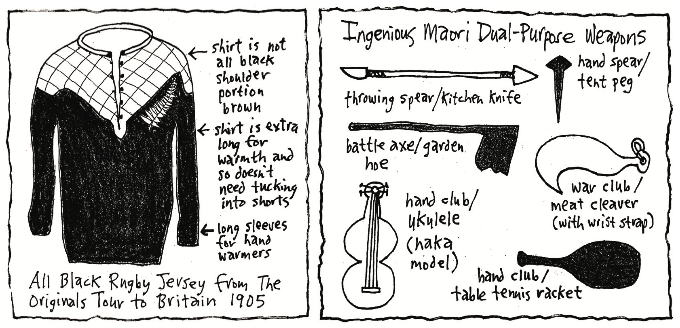

Clothing was optional (it got in the way). Warriors followed a leader, but only as long as he held their respect, and only as long as they wanted to stay. If they wanted to leave the war party, they did. A brave successful leader gained followers, and a defeated leader lost them.

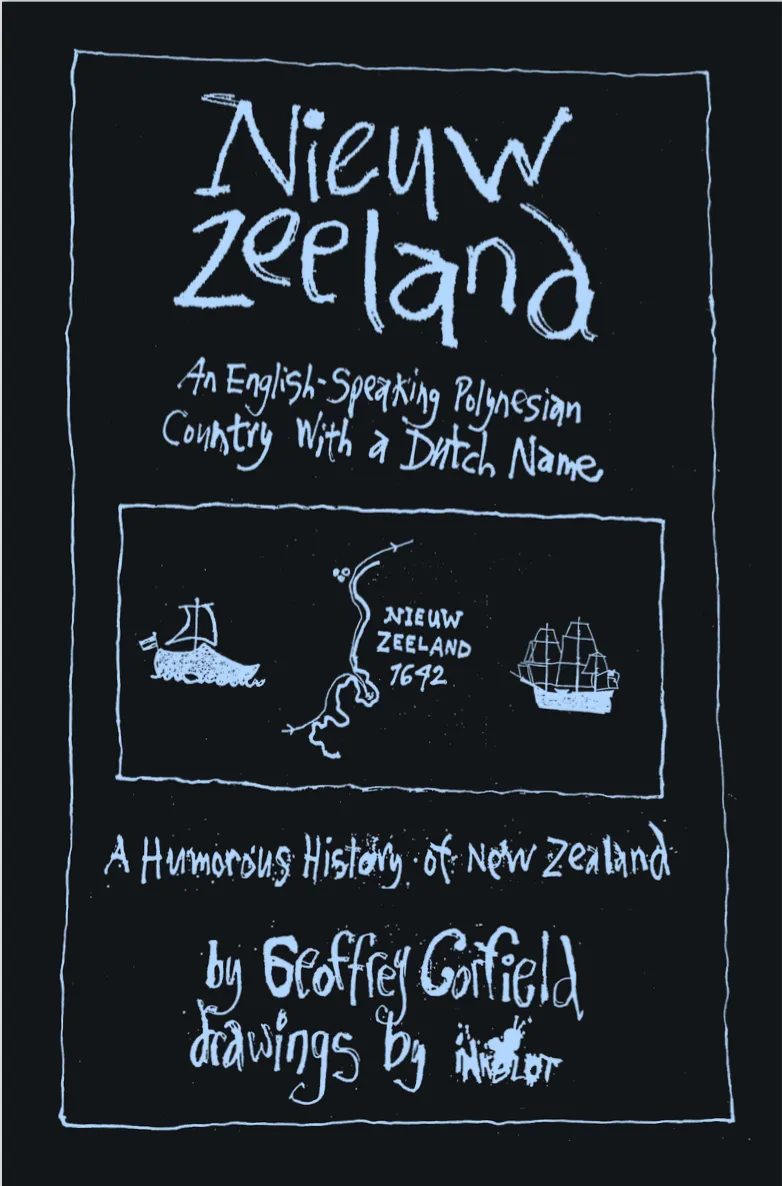

Forts were built on the tops of hills or natural defensive positions (islands, river cliffs), and either encircled an entire village or were somewhere nearby where people could retreat to when attacked. They were considered permanent structures, but seldom re-occupied if captured. Wooden stockade walls, fighting platforms (from where defenders could poke long spears at attackers), fortified buildings, and concealed interior walls and passageways into which attackers could be lured and trapped; provided solid protection against an enemy at- tacking with only clubs and spears. As a result forts were often captured more by surprise or trickery than by assault.

At Hawera, Taranaki, a Maori tribe in a fort were offered to be tattooed by a rival tribe, who tattooed the warriors of the fort on their hips and thighs so that they were sore the next day. The tattooing Maori then attacked the fort and massacred the tattooed Maori. Clever.

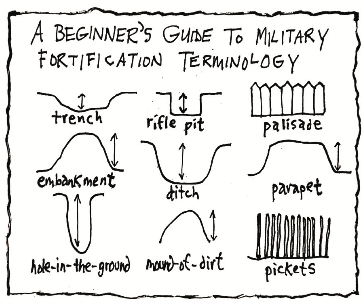

Guns however changed everything. Exposed defenders could be shot. The Maori adapted. They dug trenches, earthworks and rifle pits behind which defenders could hide. Walls were made tighter, thicker and in layers. Forts were located in open areas so attackers had nothing to hide behind, and built in square and triangle shapes to permit various firing angles for defenders. Forts were now also considered semi-permanent, and routinely abandoned if necessary.

By the time the British started fighting the Maori regularly in New Zealand, the Maori had already had 20 years experience in warfare with muskets against each other. When the British introduced artillery into war, the Maori just adapted again.

They built fortifications with thicker, heavier rows of walls in zig-zag shapes, with an outer wall often wrapped in flax matting to deaden cannonballs. Inside they dug underground tunnels, bunkers, bombproof shelters and escape routes. Eventually they built no palisade walls at all, just earthwork entrenchments and outer obstacles to slow down attackers so the defenders could shoot extra volleys at them. These earthwork defences provided strategic firing positions and sections that appeared weak to the attackers from the outside, but led them into a trap.

The British strategy for attacking these Maori forts then had to adapt too. Their initial strategy was bombardment with artillery followed by an infantry assault. But they found that even days of cannonballs did nothing, and assaults were very costly in lives. They adopted sapping (tunneling) which was time consuming but less costly in casualties. In the end though they often found that the Maori had abandoned the fort before they could capture it. The only way to stop their escape was to completely encircle them. But the Maori often escaped anyway.

Earthworks devised originally by the Maori and marvelled at by British Army engineers in New Zealand in the 1840’s, were reproduced 75 years later in Europe in the trenches of the battlefields of World War I.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Three

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Four

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part One

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part Two

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.