Table of Contents

There’s been much talk of ‘two-tier policing’ and a ‘two-speed economy’. An even more stark division, though, is the ‘two-speed culture’.

The divide is clear and yawning: between a minority of wealthy elites in the innermost big cities and a majority of struggling non-elites in the vast sprawl of suburbia and rural areas. One has the ear of political parties, the other is paid lip-service occasionally – but studiously ignored, if not actively punished, by policies.

It must be clarified, first, who the ‘elite’ really are.

While Guardian-reading types still peddle early-20th century socialist propaganda images of cigar-smoking billionaires in top hats, the real elite today are more likely to be wearing a keffiyeh and brandishing an almond-milk latte. Guardian readers, much as they would furiously deny it, are the elite. But, with household incomes over $120,000, they’re in the top 10 per cent of earners – and well on their way to the literal ‘one per cent’.

They are not ‘the 99 per cent’ they continually blatherskite about.

They’re the ones living in fashionable, multi-million-dollar terraces in the hip inner-city suburbs. Like most left-wing politicians, they are the beneficiaries of private schooling, or at best ultra-selective government schools and an arts degree education from an elite university. They almost certainly vote Green (the Greens have the richest voters) and holiday overseas at least once a year – even as they rail against ‘carbon emissions’.

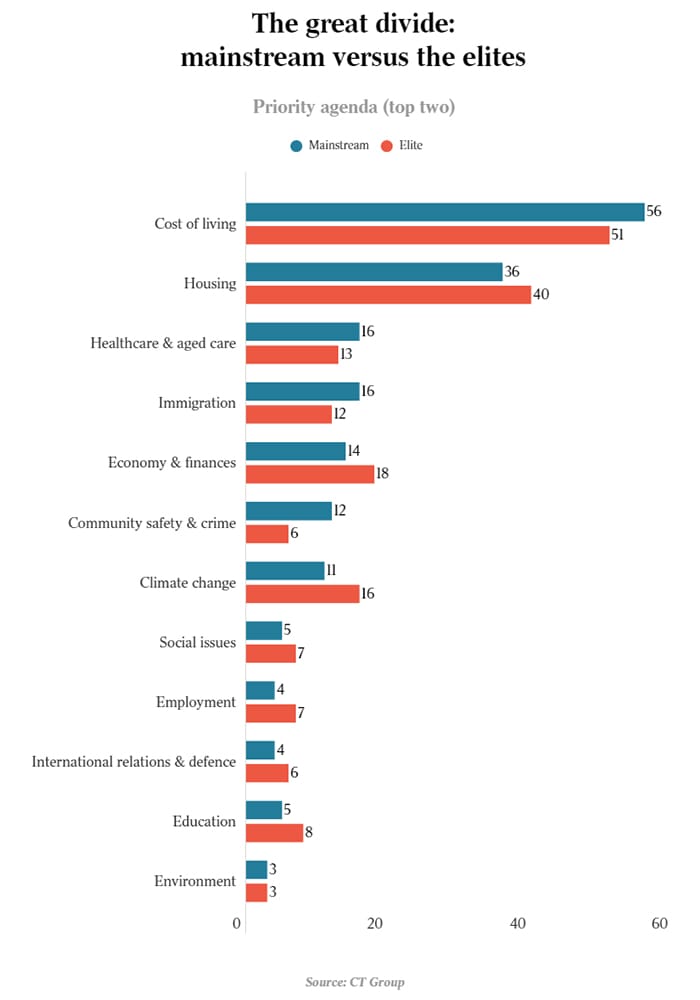

Targeted polling of 4172 Australians reveals splits between elites and non-elites on issues including migration, trust in government, climate change and leadership.

New research by leading pollster CT Group, which mirrors similar electoral projects in the US and is being driven by the firm’s executive chairman and co-founder Lynton Crosby, found the gaps between mainstream Australia and elites were growing, with lower-income voters expressing greater frustration and pessimism.

That’s because everything governments and their massive (and ever-growing) public sector dependents do is tailored to pander to the conceits of the elite. Energy policy and immigration, especially. ‘Climate change’ is a boutique obsession for the wealthy elite. Ordinary folk are far more alarmed by their electricity bills.

In a rare, wide-ranging interview with The Weekend Australian Magazine this Saturday, Sir Lynton – who built election-winning machines around John Howard, David Cameron and Boris Johnson among others – warned business leaders and politicians needed to stop selling messages through the elite lenses of their own staff to succeed in the long term.

“Politicians and business leaders need to properly understand the audience to which they’re communicating … and not to see things through the prism of the person communicating,” Sir Lynton said.

“A lot of people would say: ‘I didn’t meet anybody who supported Brexit’ or ‘I didn’t meet anyone who opposed the voice’ and that’s because you’re getting that disconnect between political, business, media and advertising leadership and the broader audience.

“There’s a values disconnect and values are the most powerful motivator of people. And if you can connect with people at a values level, then you can be persuasive.”

As former British PM Liz Truss recently said, even so-called conservative parties are run by and for people who are far too worried about being invited to fashionable dinner parties than making good policy for the country.

Asked whether gas, meat and electricity should be strictly rationed in response to climate change, mainstream voters were significantly more opposed than the elite class.

On migration, almost 60 per cent of mainstream voters said immigration numbers should be reduced compared with 39 per cent of elites. There was also a significant difference on whether migration “greatly improves the country”, with 58 per cent of elites agreeing compared with 37 per cent of mainstream Australians. Almost half of mainstream voters believe immigration “fundamentally changes the country in a way I don’t support”.

Questioned about the national direction, elites were significantly more likely to believe Australia was heading in the right direction, compared with more mainstream voters feeling the country was heading in a seriously wrong direction.

In relation to personal finances, elites on balance saw their situation as marginally improving over the next year, while the majority of mainstream voters believed theirs would get worse.

Of course the elites think things are getting better: they have the ear of the politicians who are just like them. Then they wonder why voters are deserting them in droves.

The longer politicians ignore the mainstream, though, the worse they will ultimately pay.

Ms Douglas said structural electorate changes were likely why voters were looking to independents, minor parties or anti-Establishment candidates “to vent frustration”.

On the other hand, major party politicians who pay attention will reap the rewards.

For the first time in history last weekend, the Liberal National Party won the Labor stronghold seats of Rockhampton and Mackay at a Queensland election. Even at the ALP’s lowest ebbs during the Joh Bjelke-Petersen era and Campbell Newman’s 2012 landslide, Labor still held on to the central Queensland seats […]

In the wake of the 2022 election defeat, Mr Dutton and the Coalition have shifted attention to outer-suburban and regional seats, in the hope of offsetting falling support in inner-city seats.

The elites are solidly left wing. But there’s a vast pool of centre-right voters in the suburbs and countryside who are desperate for anyone to actually listen to them.