Table of Contents

Jennifer Sey

Jennifer Sey is filmmaker, former corporate executive, and author of Levi’s Unbuttoned.

I’m a feminist. I have no problem with this “F” word and never have.

There have always been women who rejected the label. When I was a college student in the late 80s-early 90s, some women rejected the word and identification because they associated it with stereotypical traits like stridency, anger, a lack of a sense of humor, and hairy legs. Those associations never concerned me.

Some do not claim the label because they feel the movement hasn’t done much to address the challenges of all women. Race can play a role in identifying as a feminist, for instance. More white women claim to be feminists than black women. I understand this.

But I agree with Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who wrote the essay (and delivered the TED talk) We Should All Be Feminists. Whether or not the movement has lived up to its promise (it hasn’t), the goal of undoing the gender hierarchy is worth continuing to strive for.

At the core of my feminist beliefs, I agree with this statement by Adichie in her essay: “We teach females that in relationships, compromise is what a woman is more likely to do.” I’d argue we don’t only teach females that it is more likely but also more desirable.

I’d like to see that undone. We aren’t there yet. In some ways, we are going backwards.

Today the feminist movement insists that women who defend women’s safety and an equal playing field in women’s sports are anti-trans bigots. This is bullying to women. And it’s a lie. And it is weaponizing our empathy against us, while reinforcing the orientation that women must compromise to make others more comfortable.

I believe in equal rights and equal opportunity for women. I believe women have a right to safe single sex spaces in locker rooms, on university campuses, in prisons and in battered women’s shelters. And in sports. Period. That, to me, is feminism.

My feminist awakening came during college when I read Gloria Steinem’s Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. I was captivated by academic analyses of “the male gaze” in my feminist studies and literary theory and criticism classes. I was anti-porn and pro-sex and briefly bisexual (as one was, in college at the time.)

I came to understand that I had benefited from Title IX’s passage in 1972 and then I fought to continue to push for women’s equality in education on my own campus at Stanford University. I marched to take back the night and I pushed my professors to expand “the canon,” to include black female writers like Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston, in addition to Willa Cather and Jane Austen.

I worked at the National Organization for Women in Washington, DC the summer before my senior year, and I rallied in defense of choice.

It took me a few more years to overcome an eating disorder, but that recovery was driven by my newly awakened feminism. My aha moment came when I realized that in associating my value with my appearance, I was holding myself back in a way that a young man my own age never would.

I was conceding my own unequal status by accepting the terms of the patriarchy. Or something like that. Gibberish maybe, but it worked. I stopped fasting and binging and purging and got to the business of living and striving. Reading Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth didn’t hurt in that process.

I moved into the workplace in the mid-90s and found there were still hills to climb for women. There were zero female leaders except maybe in support functions — departments like Human Resources and Corporate Communications might be led by women but that was it. They were advisors to the “real” business leaders (the men). These women spoke in hushed tones and leaned into the President’s ear during executive meetings to give advice and were often waved off. They counselled, they didn’t control or decide. They influenced (kind of), but they didn’t lead.

My reading evolved. I read bell hooks and then Susan Faludi and then Rebecca Walker and contemplated the third wave of feminism. I loved Thelma and Louise and I watched Anita Hill’s testimony accusing Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment with rage.

Third Wave Feminism’s assertion of sexual liberation — which often felt like gratuitous promiscuity to prove a point — never appealed to me. I wasn’t a prude. But the idea that I should have tons of meaningless sex was not only unappealing but felt like I’d be setting myself up for disappointment. Trying it out did result in a lot of angst. I wasn’t so good at detachment. I suppose I’m a demisexual, which would make me Queer in today’s lexicon. Also known as a pretty typical woman, at least for members of my Gen X cohort.

Later, I leaned in, before Sheryl Sandberg told me I was supposed to. I defended my working mom and sole breadwinner status at the height of the mommy wars. I rose up the corporate ladder and learned I could ensure equal pay and opportunity best by being in the arena, rather than pushing for it from the outside.

And when, during lockdowns, I opposed prolonged public school closures (and lost my job over it), it was not just children and their right to an education I was standing up for. It was women too. Women who disproportionately are primary caregivers for their children, even while they work full-time.

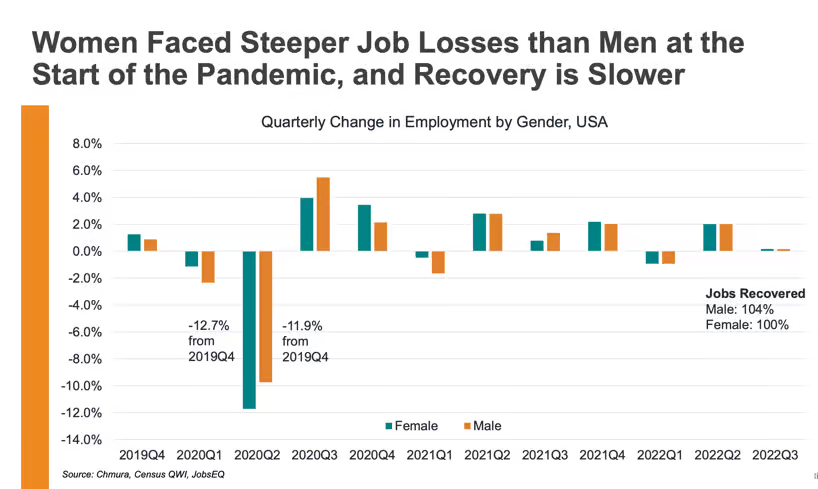

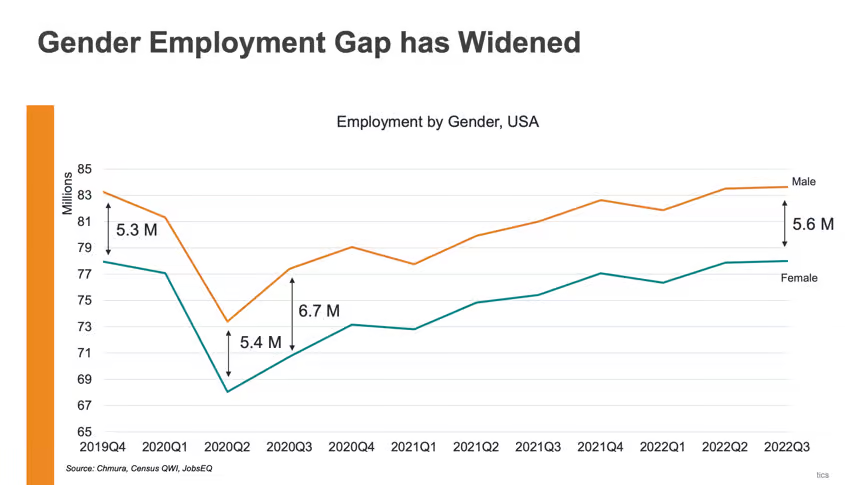

And it was women who dropped out of the workforce in droves during COVID-19, out of sheer necessity in order to educate their children when Zoom school proved useless. And it is women who are still lagging in returning to the workforce today, more than 3 years later, as we experience a widening gender employment gap.

During my time in corporate America at Levi’s, I fought for the women on my team. One of the first things I did when I became the Chief Marketing Officer in 2013 – managing a team of nearly 800 people – was a salary assessment across gender and other key populations. Unsurprisingly, there was a gender pay gap, and we corrected it.

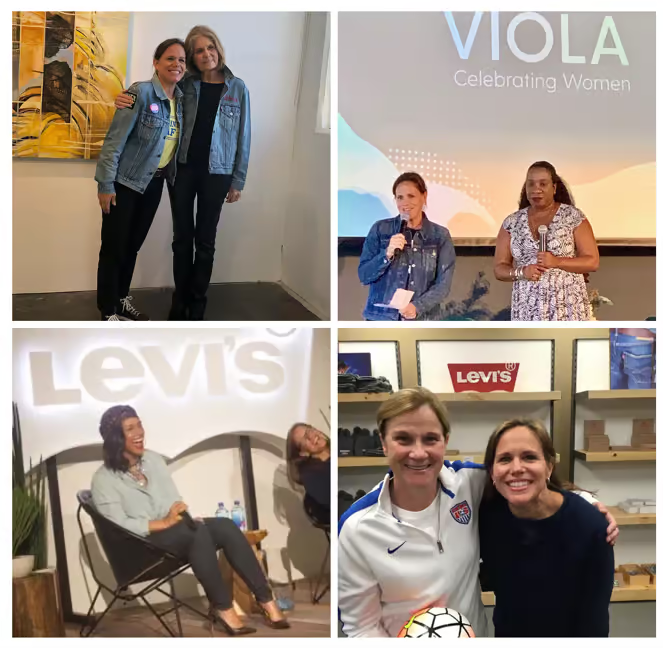

I also tried to inspire and engage female employees to forge ahead, despite setbacks they might experience. I mentored Millennials and Gen Z women. I brought in speakers like Gloria Steinem, Tarana Burke, Alicia Keys, and former US Women’s Soccer coach Jill Ellis (who led the team to 2 World Cup victories) to share their personal stories of adversity and triumph.

I was the woman in the arena. For over 30 years.

My feminist awakening reads like a cliche for any left-leaning Gen X woman with a college education. But it’s mine. I learned to push back, to speak up, to say no and not just accept that the comfort of men is more important than my own. (That took a while to put into practice.)

Eventually, I had a minor supporting role in the #MeToo movement because I produced an Emmy-winning film called Athlete A which exposed the brutality of abuse — sexual, physical, and emotional — in the sport of gymnastics. I felt as if I was pleading don’t forget the young athletes abused by coaches, amidst the shinier stories of movie stars coming forward to expose Harvey Weinstein. The film highlighted and spurred the athlete movement against abuse in sport — us too, it seemed to say.

And so, it is with great dismay that I wonder now, where are you all? All of you who I came up with to fight for the rights of women — we fought for women’s safe spaces, we shouted No means no! and Take back the night! as we marched across campuses. But where are you now? Do you no longer care about the safety of women? The equal opportunity?

Where is your riot girrrl growl, in defense of women in sports who just want an equal playing field? Where are you now when Paula Scanlan testifies before the House Judiciary Subcommittee and says: “I know of women with sexual trauma who are adversely impacted by having biological males in their locker room without their consent. I know this because I am one of these women?”

Just 5 years ago, at the height of the #MeToo movement, if a woman said I was me too-ed when I went on a date with Aziz Ansari. He disrespected me when he ordered the wrong kind of wine, she would have been validated and gotten her story published on babe.net (even though it all seemed a little over the top and perhaps a truly shark-jumping moment for the movement overall).

Now, Scanlan is sent to psychotherapy by her university for saying that as a victim of sexual assault, she isn’t comfortable changing in a locker room with a biological male, in her case, transgender swimmer Lia Thomas. Scanlan is smeared as a bigot when she says I don’t feel safe. I’m a victim of sexual assault and I’m not comfortable in a locker room with a biological male, genitals intact and exposed. She is told by her university she must enter therapy to learn to be comfortable.

What happened to believe women? Or is it just women with penises we are supposed to believe and support now? The rest of them — 1 in 6 who have been victims of sexual assault — are once again supposed to quietly accede to the demands of others? To women with penises? Trans women are women, the trans activists yell at us. At Scanlan.

I was in Washington, DC on February 1, 2017 for the first meeting with Senator Dianne Feinstein to discuss athlete safety and abuse. I travelled across the country to Washington with my then 2-month-old daughter to meet with the Senator, along with about 10 other athletes, most of whom were sexually abused by Larry Nassar.

During that first meeting, I was the “oldster” in the room, serving as the voice of history. I was included to emphasize the fact that abuse had been happening long before Nassar — the now disgraced former team doctor for Team USA Gymnastics who is in prison for life for sexually abusing hundreds of young athletes — became infamous. His ability to abuse for so long was the result of a rotten culture that permitted the abuse of athletes. He sexually assaulted athletes for more than 3 decades because he was allowed to. Leaders in the sport — people like former USA Gymnastics (USAG) CEO Steve Penney — knew and looked the other way. They were not recognized legally as mandatory reporters, therefore they were not required to report suspicion or knowledge of abuse. So they didn’t.

We all told our stories to the Senator and Feinstein promised on that day: I will pass a law to protect young athletes. The law can be helpful but it is the culture that will need to change. And that is even harder than passing laws. You will have to do that work.

Later that year, the Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act — or the Safe Sport Act, as it is commonly known — was passed into law.

SafeSport, a non-profit established in late 2017 under the auspices of the Safe Sport Act, was created as an independent body (independent from the US Olympic Committee or USOC) to help protect athletes.

The SafeSport organization has defined prohibited behaviours, they provide coach training and education, they have laid out policies and procedures for reporting abuse, and have established a formal process whereby athletes and an expanded list of mandatory reporters can report abuse to SafeSport. They also investigate and resolve claims of abuse.

SafeSport teaches athletes and other observers of sport (parents, administrators, etc) that if you see something say something. If you are uncomfortable, report it. If the behaviour is clearly illegal, report it to the police. If it is less clear — perhaps grooming behaviour like a male coach talking about his sexual exploits to a 10-year-old (this was a common experience for me in the 1970s and 1980s in gymnastics) — report it to SafeSport.

The influx of reports into SafeSport has been overwhelming and difficult to manage. They are receiving over 150 reports a week, on top of 1,000 open cases. Criticism is mounting. Last year, former US Attorney General Sally Yates concluded that SafeSport “does not have the resources necessary to promptly address the volume of complaints it receives.”

Despite being underfunded, SafeSport’s mission remains clear: protect athletes from abuse.

If a female coach is naked in a locker room and parading around, getting too close to minor female athletes, that is reportable, if it makes a young girl uncomfortable.

But what if Lia Thomas does the same? Is it not reportable because trans-women are women? But it is reportable if a biological woman does it? Based on Scanlan’s experience, that does indeed seem to be the standard now in play. (I’ll grant that Scanlan most recently swam under the auspices of the NCAA, not the USOC or USA Swimming — but I would have thought that given the #MeToo movement, Title IX, and the principles established by SafeSport that there would be a comparable standard within the NCAA. I’d be wrong, at least when it comes to the issue of transgender athletes in women’s locker rooms.)

It doesn’t make any sense. What happened to prioritizing the voices of survivors?

I fought too hard and for too long to shut up now. It took more than 20 years from the time I realized I had a voice until I actually used it to advocate for myself and other athletes coming up in the Olympic movement.

I know many women who are whispering in the shadows, telling their friends in kitchens across the country — there is something wrong here. I would submit to you: we were told to be quiet when men assaulted us and then we finally said no we aren’t going to be quiet. We screwed up our courage and we took back the night. We said my comfort and safety matter.

We refused to be intimidated then, and yet, we allow ourselves to be intimidated now. We are doing it all over again — allowing others’ needs and wants to come before our own. And now the far-left — through sheer force of intimidation and the threat of a smear campaign against any individual who dares to speak up — has got women who are afraid of being called bigots (we used to be afraid of being called prudes) doing their bidding.

Of course, all transgender women are not going to take advantage of this situation to abuse. And not all coaches do either. But some do. The overwhelming reports of abuse to SafeSport today are proof of just that. Regardless, the standard in recent years as prompted by the #MeToo movement is centred around the physical and emotional safety of women. Why not now?

There are solutions for inclusivity that do not include silencing and smearing women and telling them they need to put their own fear and discomfort aside.

As Senator Feinstein told me, culture change is hard. But that is what we face at the moment, although in unexpected ways. We still deserve safe spaces and equality of opportunity.

And so, I am still a feminist. And I’m using my voice. I’m urging my fellow feminists to do the same.