Table of Contents

A stunning leaked cache of police data has opened a disturbing window into China’s gulags in Xinjiang. The leak includes spreadsheets and thousands of photos of detained Uighurs. The trove of shocking material was leaked to the BBC earlier in the year, and the broadcaster has spent the months since investigating and verifying them.

The cache reveals, in unprecedented detail, China’s use of “re-education” camps and formal prisons as two separate but related systems of mass detention for Uyghurs – and seriously calls into question its well-honed public narrative about both.

The government’s claim that the re-education camps built across Xinjiang since 2017 are nothing more than “schools” is contradicted by internal police instructions, guarding rosters and the never-before-seen images of detainees.

The images are horrifyingly reminiscent of the tens of thousands of photos of their victims, taken by the genocidal Khmer Rouge communists.

The documents provide some of the strongest evidence to date for a policy targeting almost any expression of Uyghur identity, culture or Islamic faith – and of a chain of command running all the way up to the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping.

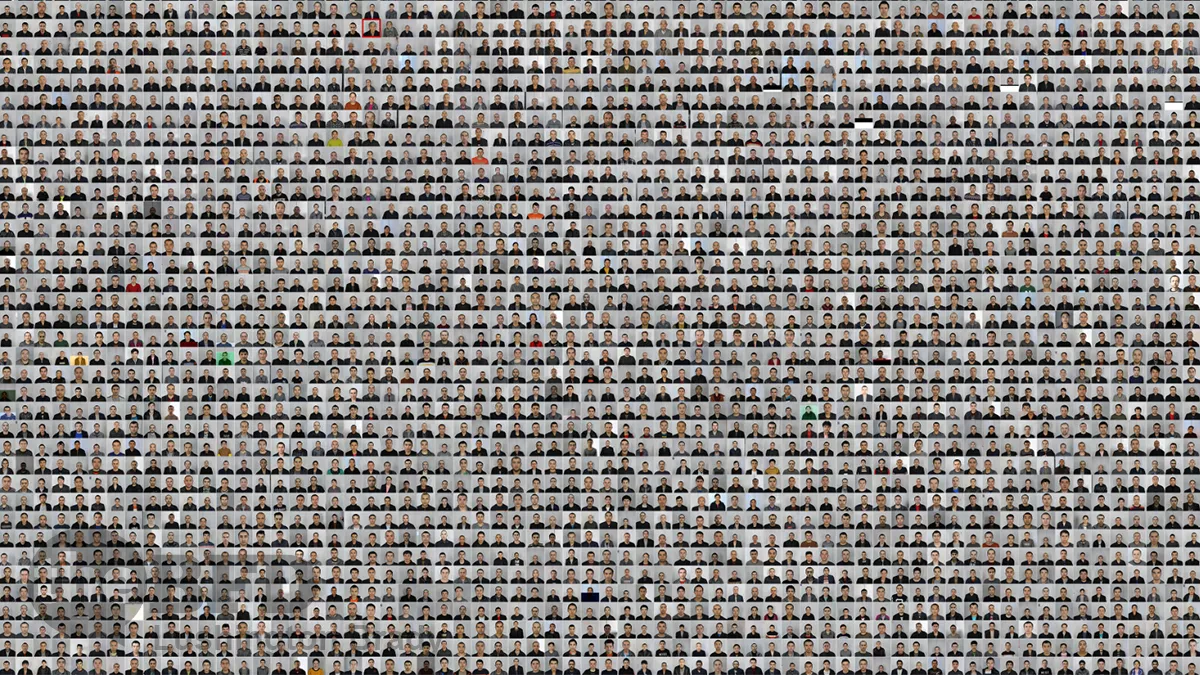

The hacked files contain more than 5,000 police photographs of Uyghurs taken between January and July 2018.

Using other accompanying data, at least 2,884 of them can be shown to have been detained.

And for those listed as being in a re-education camp, there are signs that they are not the willing “students” China has long-claimed them to be.

Some of the re-education camp photos show guards standing by, armed with batons.

A time-lapse compilation of the photos shows that they appear to have been taken in the same spot — a simple screen pulled down to hide the cells behind — with the same guards lurking at the edge of shot.

The photos and files show detainees ranging from just 15 to 73. Other photos show sisters aged just 10 and six, whose parents were detained.

The spreadsheets give few details about the fate of such children whose parents have both been detained.

It’s likely a significant number have been placed into the permanent, long-term care of a system of state-run boarding schools built across Xinjiang at the same time as the camps.

In fact, the closely shaved hair visible in so many of the images of children is a sign, overseas Uyghurs have told the BBC, that many are already made to attend such schools at least during weekdays, even if still under the care of one or both parents.

The files are claimed to have been hacked, downloaded and decrypted from police servers in Xinjiang. They were then passed on to Dr Adrian Zenz, a scholar at the US-based Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a key researcher into the genocide in Xinjiang. The fact that none of the hacked files are dated later than 2018 indicates that they pre-date a security crackdown by the Chinese government in 2019.

“The truth is the education and training centres in Xinjiang are schools that help people free themselves from extremism” — Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

The Xinjiang Police Files contain another set of documents that go even further than the detainee photographs in exposing the prison-like nature of the re-education camps that China insists are “vocational schools”.

A set of internal police protocols describes the routine use of armed officers in all areas of the camps, the positioning of machine guns and sniper rifles in the watchtowers, and the existence of a shoot-to-kill policy for those trying to escape.

Blindfolds, handcuffs and shackles are mandatory for any “student” being transferred between facilities or even to hospital.

The CCP claims that their crackdown is because of Islamic terrorism, but the files show that it is an ethnic and cultural genocide where citizens are detained on the flimsiest of pretexts. One man is listed as jailed for 10 years for having “studied Islamic scripture with his grandmother” for a few days in 2010. Hundreds are listed as detained for listening to “illegal lectures” on their mobiles, or having encrypted apps installed. Over a hundred are cited for “phone has run out of credit”, supposedly a sign that they were trying to evade China’s constant digital surveillance.

If the terrorism label is ever justly applied, it’s impossible to discern among a sea of data pointing to the internment of a people not for what they’ve done, but for who they are.

Tursun Kadir’s spreadsheet entry lists some preaching and studying of Islamic scripture dating back to the 1980s and then, in more recent years, the offence of “growing a beard under the influence of religious extremism”.

For this, the 58-year-old was jailed for 16 years and 11 months.

But the leaked cache reveals something even more disturbing: entire communities of Uighurs, from the elderly to children, were forced to file through police stations at all hours, simply to have their photographs taken and details recorded.

A similar file-naming system as that used for the photos taken in the camps and prisons suggests a possible common purpose – a huge facial recognition database that China was building at the time.

An analysis of the data by Dr Zenz suggests that in one county alone, over 12 per cent of the adult population were detained by Chinese authorities in 2017-18.

If applied to Xinjiang as a whole, that figure would mean the detention of more than 1.2 million Uyghur and other Turkic minority adults – well within the broad range of estimates made by Xinjiang experts, which China has always dismissed.

BBC

In a speech – stamped “classified” – recorded in the cache, China’s Minister for Public Security, Zhao Kezhi, claims that at least two million people in southern Xinjiang alone harbour “extremist thought”.

Even more ominously, a secret speech by Communist Party secretary Chen Quanguo argues that gulags and “re-education” is not enough. “Once they are let out, problems will reappear.”

Which begs the obvious question: what recourse does that leave the CCP?

Ask the spirits of those staring out of the photographs of Cambodia’s Killing Fields just how it will end.