Table of Contents

20th May 2021

Demonstrators are leaving the cities and secretly making their way to the ethnic conflict zones. They are looking at two options after training – either to swell the ranks of the EAOs or to develop guerrilla actions within the cities.

The Myanmar regime has objected to the provision of military training by the country’s oldest ethnic armed group to protesters who have resolved to take up armed struggle to topple the junta.

Following the regime’s deadly crackdowns on pro-democracy protests on the streets across the country in March and April, a number of anti-regime protesters fled to areas controlled by ethnic armed groups on the border. They have received military training there from some ethnic armed groups who are against military rule in the country.

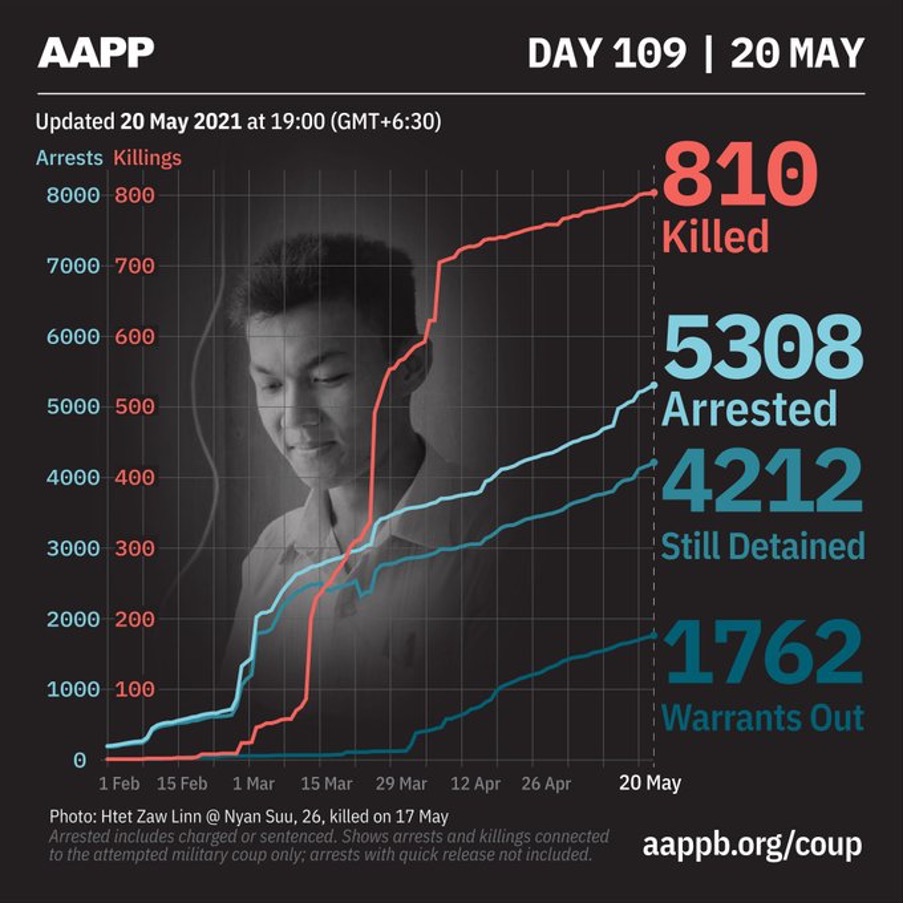

As of Wednesday, more than 800 people had been killed by the regime since the Feb. 1 coup, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners-Burma (AAPP), which has been monitoring civilian casualties caused by the junta.

The exact number of the trainees on the border is unknown. But according to some media estimates there may be at least several hundred, including doctors and other young professionals.

On Tuesday, the regime’s governing body in Karen State in southern Myanmar sent a letter to the Karen National Union (KNU) and its armed wing’s liaison office.

The letter said the regime had learned that the KNU’s Brigades 1, 6 and 7 have provided military training to some people affiliated with the shadow National Unity Government, its parliamentary committee and its defence force in their areas of control. The regime has branded those groups as terrorist organizations.

“We object to the action as it’s found that the KNU is intentionally harming the government administrative machinery while breaching the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) [provisions on] ‘regional stability and rule of law,’” it said.

So far, the KNU hasn’t said it has been providing the training.

The KNU has been fighting for autonomy since Myanmar’s independence from the British in 1948. It signed the ceasefire agreement with the central government and the military in 2012.

Despite the agreement, one of its brigades has launched attacks against the regime’s troops near the Thai border as it is not happy with the coup. In the country’s north, another major ethnic armed group, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), has been waging war against the regime’s troops for a month as it opposes the coup and the regime’s deadly crackdowns on protesters. The regime has retaliated against both armed groups with airstrikes, leaving many civilians displaced from their homes.

The junta’s objection against the KNU follows last week’s arrest of 39 people who according to military-owned media are suspected of orchestrating explosions and arson attacks, as well as seeking military training with an ethnic minority rebel group. In the letter to the KNU, the regime said it had learned of the armed group’s involvement while interrogating the detainees.

A number of police stations, government schools and local administrative offices have been set on fire or bombed across the country while some regime-appointed local officials have been killed by unknown attackers.

Source The Irrawaddy 19th May 2021.

The armed conflict has spread throughout the country. The EAOs have still got RPGs and are trying to source Stinger ground to air missiles.

Another military airbase has come under rocket attack in central Myanmar, a shadowy but strategic assault that even tightly censored, military-controlled media felt compelled to report.

On May 15, three 107mm rockets were fired at Toungoo airbase, situated just 95 kilometres from the capital Naypyitaw, according to the state mouthpiece Global New Light of Myanmar. The rocket attack follows similar assaults on air bases at Magwe and Meiktila in late April.

No group has claimed responsibility for the attacks, but they come after recent Tatmadaw aerial bombardments in Kayin and Kachin states, where ethnic armies are battling the military and anti-coup protesters have recently taken refuge from rising, lethal military violence in urban areas.

Myanmar’s civil wars, until now confined mainly to relatively remote ethnic frontier regions, are now spreading to the country’s heartland and urban areas. Rather than ethnic army fighters, recent attacks have more likely been launched by new-age militants from the ethnic Bamar majority.

Shadowy attacks on military soft and hard targets are mounting. On May 18, a local junta-appointed official was assassinated in Yangon’s Lanmadaw district after two bomb blasts at his office. According to Yangon-based sources, the official was known to be a key military informant and his actions had led to the arrest of several pro-democracy protesters.

Bombs have also detonated in various towns in Sagaing and Mandalay Regions and in Shan, Mon and Chin states. When the coup leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, visited Sagaing City on May 18 a bomb exploded even there despite tight security.

A clear example of this new resistance to military rule was recently seen in Mindat, a town in Chin State but close to the border with the central region of Magwe. The Chinland Defense Force (CDF), a newly formed local militia, took over the town and retreated only after heavily armed Tatmadaw units counterattacked with artillery and helicopter gunfire.

Here is a clip of the weather in the Chin jungle where the residents are seeking refuge – it is the start of the monsoon.

Before those reinforcements arrived, local militants armed with only hunting rifles and homemade bombs killed several Tatmadaw soldiers. Until now, Chin state is the only ethnic state in Myanmar that has not seen widespread insurgency. (The ceasefire Chin National Front was never a formidable force.)

What began as peaceful, even joyful demonstrations against coup leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing’s democracy-suspending February 1 coup is now morphing into shadowy armed resistance across the country. The list of anti-military counterattacks is growing by the day.

For instance, a bomb exploded at the Daik-U township’s education office in the Bago Region on May 16. That same day, another bomb detonated at the Mogok township general administrator’s office in the Mandalay Region.

On May 17, the Htone Bo Ward administration office in Sagaing township was burned down. On May 18, a truck carrying food supplies for Myanmar army soldiers was torched on the Mogaung-Tanai Ledo road in Kachin State.

The shift from peaceful to violent protest came only after demonstrators were violently and lethally attacked by soldiers and police, with snipers shooting teenagers and even killing children as young as five, according to news reports.

Nearly 800 people have been killed by the police and Tatmadaw since Min Aung Hlaing seized power from an elected government. Close to 5,000 have been arrested, including politicians, journalists, lawyers and community workers. An unknown number are now in hiding or have fled to border areas or across the border into exile.

Yangon residents say the persistent unrest appears to be taking a toll on the mental health of front-line police and soldiers who are ordered by their superiors to use lethal force against the general population.

“They are staying inside hospitals, schools, police stations and secluded compounds and when they venture out of those, local activists inform their comrades in other parts of Yangon,” one Yangon-based source said.

Three and a half months after the coup, anti-coup demonstrators are still marching in the streets in defiance. Many others, sources say, are getting ready for more violent action.

They say the assassination of the official in Lanmadaw is probably only the beginning of what could quickly turn into urban warfare scenarios in major cities nationwide. According to some reports, automatic weapons and grenades have already been sent to activists in Yangon.

Myanmar may not become a full-blown failed state — much of the economy is and has always been run underground and thus not measured in official statistics — but the nation is definitely now a failing state.

Tens of thousands of health workers and teachers have been fired for taking part in the so-called Civil Disobedience Movement. Banks are reportedly running out of cash as people — if they are lucky — withdraw their savings. Many have imposed fees of 8%-9% to withdraw funds or imposed outright limits on the amount that can be taken out.

A brain drain has also begun as many well-educated people have leveraged various channels to leave the country. What happens next is not clear, but Min Aung Hlaing’s power-grab is measuring up as perhaps the most unsuccessful military coup in modern Asian history.

Source Asia Times May 19th, 2021.

This is all getting very messy for the regime as incompetence piles on top of incompetence.

Finally, here is today’s cumulative civilian casualty list.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD