Table of Contents

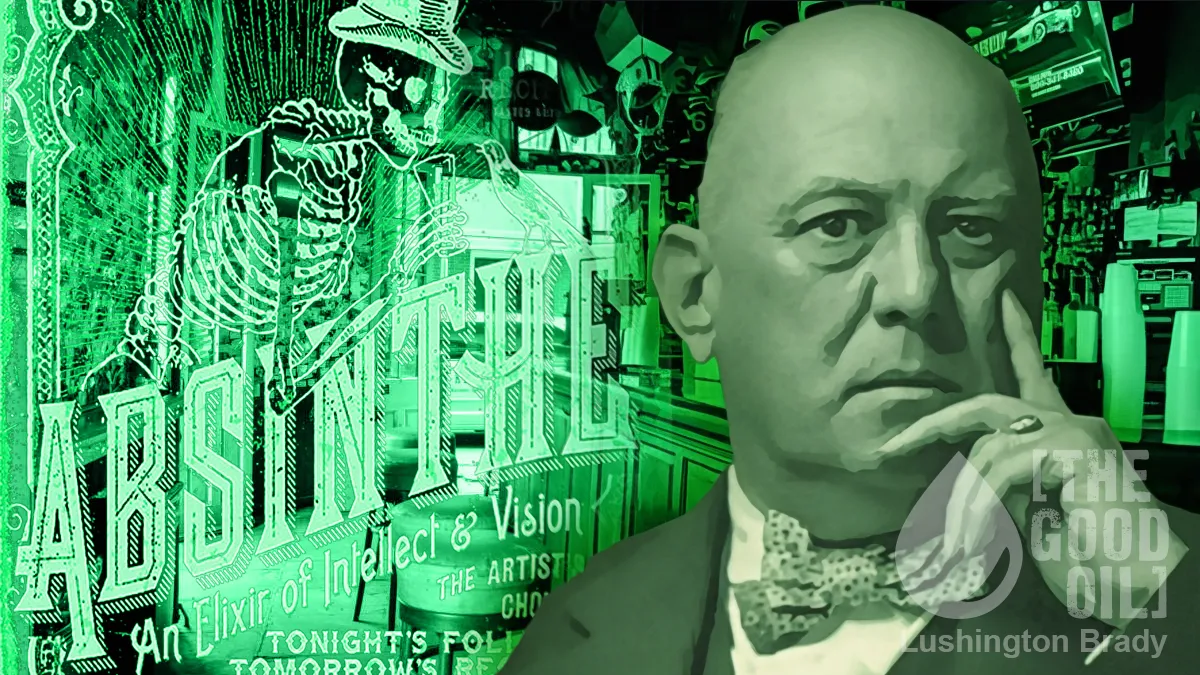

Few figures from the late 19th and early 20th century are more controversial – and frequently misunderstood – than Aleister Crowley. Occultist, mountaineer, master chess player, sex maniac, yogi, mildly talented poet, terrible painter, surprisingly good writer, drug addict and self-proclaimed prophet. Crowley’s reputation is both well deserved and too-frequently exaggerated.

He was, for instance, definitely not a Satanist, for the simple reason that he accepted neither Christianity nor its adversary. Still his occult investigations assuredly veered too often to what might be called the Dark Arts, mostly because he clearly wasted too much of his life and energies in a sustained and infantile rebellion against the hyper-puritanism of his upbringing among what today are known as the Exclusive Brethren (he adopted the “Great Beast” moniker as an f-you to his hated mother who described him as such).

If nothing else, though, Crowley had a gift for being at the right places at remarkable times: London during the heyday of the Golden Dawn society, La Belle Epoque Paris. The then-largely-unexplored (by Europeans) China and Central Asia, where he took part in a fated expedition to conquer K2. And Berlin during the rise of the Nazis (he lambasted Hitler as a “black magician”).

In 1918, Crowley visited the French Quarter of New Orleans at the tail end of the city’s cultural renaissance, which was just to see jazz become an international phenomenon – and where absinthe, officially outlawed in 1912, was still available at the famed Old Absinthe House, which still stands on the corner of Bourbon and Bienville streets.

Taking a seat, Crowley ordered a glass of the ‘forbidden drink’, “with its origins in medieval alchemy, more of a potion than a beverage historically associated with magic and witchcraft”. Then another. And another.

Pleasantly toasted and creatively inspired, he uncapped his pen and wrote a seminal essay about life, death, vice, and what it means to be an artist. He called it Absinthe, the Green Goddess, and it began like this:

Keep always this dim corner for me, that I may sit while the Green Hour glides, a proud pavine of Time. For I am no longer in the city accursed, where Time is horsed on the white gelding Death, his spurs rusted with blood.

There is a corner of the United States which he has overlooked. It lies in New Orleans, between Canal Street and Esplanade Avenue; the Mississippi for its base. Thence it reaches northward to a most curious desert land, where is a cemetery lovely beyond dreams. Its walls low and whitewashed, within which straggles a wilderness of strange and fantastic tombs; and hard by is that great city of brothels which is so cynically mirthful a neighbor…

At least the poet of Le Legende des Sexes was right, and the psycho-analysts after him, in identifying the Mother with the Tomb. This, then, is only the beginning and end of things, this "quartier macabre" beyond the North Rampart with the Mississippi on the other side. It is like the space between, our life which flows, and fertilizes as it flows, muddy and malarious as it may be, to empty itself into the warm bosom of the Gulf Stream, which in our allegory we may call the life of God.

Crowley had made his way to New Orleans from New York, where he had arrived, broke, having spent his substantial inheritance over 30 years of global travel and libertinism. Relying on members of his occult order and his income from writing, he toured the United States from coast to coast, before in New Orleans, his favorite city in the US.

Like many artists before and since, Crowley immediately felt at home in the French Quarter. And as he stared into his glass of absinthe, he mused about the magic of the creative process, speaking of it in monumental, even biblical terms.

Originally in the fantastic but significant legend of the Hebrews, the rainbow is mentioned as the sign of salvation. The world has been purified by water, and was ready for the revelation of Wine. God would never again destroy His work, but ultimately seal its perfection by a baptism of fire…

Can it be that in the opalescence of absinthe is some occult link with this mystery of the Rainbow? For undoubtedly one glass does indefinably and subtly insinuate the drinker in the secret chamber of Beauty, does kindle his thoughts to rapture, adjust his point of view to that of the artists, at least to that degree of which he is originally capable, weave for his fancy a gala dress of stuff as many-colored as the mind of Aphrodite.

With his usual impeccable timing, Crowley arrived in New Orleans at “the tail end of one of the most dynamic periods in its history”. The Antebellum ‘Jewel of the Mississippi’ had been hit hard by the aftermath of the Civil War. After the failure of Reconstruction, the city was in hard times, especially for poor black and Creole communities. Unsurprisingly, vice flourished as a welcome distraction: drinking, dancing, sex and, especially, music. Neighbourhood brass bands, mostly but not exclusively black, were experimenting with a hot, energetic, new style of music. It didn’t have a name yet, but it was about to take the world by storm.

New Orleans in the second decade of the 20th century was the midwife of the Jazz Age.

As Crowley sat in the back of the old absinthe house in 1918, getting wasted and scribbling on a piece of paper, he was surrounded by the afterglow of a legendary American Bohemia, where genius and vice swirled together as surely as wormwood and sugar. I like to think it was the great duality of this beautiful, wretched city that inspired Crowley to write:

The genius feels himself slipping constantly heavenward. The gravitation of eternity draws him. He is like a ship torn by the tempest from the harbor where the master must needs take on new passengers to the Happy Isles. So he must throw out anchors and the only holding is the mire! Thus in order to maintain the equilibrium of sanity, the artist is obliged to seek fellowship with the grossest of mankind.

Such sentiments were the cornerstones of Crowley’s life, where artistic genius wallowed in the mire of degradation. A psychologist would have a field day with Crowley: the rebellious son of a hyper-puritan mother, whose holy grail was a ‘Scarlet Woman’ who would beat and degrade him during sex.

Absinthe was the spirit of such a world.

Absinthe conjures for us a lost world. The time of the French bell epoch with its countless cafes, its bohemian artists and poets, the early days of electric light, the 1889 World's Fair, just as the Eiffel Tower went up. It was a world before world wars and atomic weapons. It's a world near to us and yet separated by an unimaginable gulf. And that lost world of the arcades and the flaneurs was fueled by absinthe.

And absinthe embodied Crowley’s worldview: heady and allegedly psychoactive (mostly due to cheap knock-offs heavily adulterated with poisonous chemicals), inspiring rapturous artistic visions, even as it became synonymous with vice and squalor. Characteristically, Crowley had withering contempt for the Prohibitionists, whom he regarded as rank hypocrites.

The Prohibitionist must always be a person of no moral character; for he cannot even conceive of the possibility of a man capable of resisting temptation… With this ignorance of human nature goes an ever grosser ignorance of the divine nature. He does not understand that the universe has only one possible purpose; that, the business of life being happily completed by… religion, love, and art. These three things are indissolubly bound up with wine, for they are species of intoxication.

‘So crass a creature,’ he wrote, purports to be motivated by religion: ‘but what a religion…! Art is for him the parasite and pimp of love.’

Wine is the ripe gladness which accompanies valor and rewards toil. It is the plume on a man's lance head, a fluttering gallantry, not good to lean upon.

In some ways, here, Crowley is anticipating the spirit of the Surrealists, whose maxim was Rimbaud’s “systematic derangement of all the senses” – a derangement which must be tempered by the discipline of the artist.

Aleister Crowley’s 1918 essay captures something powerful and timeless, the magic of a place and time that endures both storms and tourists. Some of the soul of New Orleans captured in the spiritual heart of the French Quarter.

And who better to capture that spirit, that magic somehow paradoxically between both saint and sinner, than the great beast 666 while tippling the green fairy at the Old Absinthe House.