Table of Contents

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand by Geoffrey Corfield from Amazon today.

Orakau, near Te Awamutu, 30 March-2 April 1864

One of the most famous battles of the British-Maori Wars. The King Maori (300-400), fortify a spot on a curving ridge with rifle pits, ditches and posts and rails. There is a forest on one side and a swamp on the other. The government army (1,239) surrounds them. The King Maori have little food, water or ammunition. Reinforcements from the east cannot break through the British siege ring. The government begins tunnelling towards the defences, receives 400 reinforcements, and breaks through into the fortress after three assaults.

The King Maori are asked to surrender. Chief Rewi answers: “Peace shall never be made, never, never. My friend, we shall continue to fight you to the bitter end, forever and forever” (or words to that effect).

The King Maori are asked to release the women and children. Chief Rewi answers: “The women will fight too. If the men die, the women and children must die also” (or words to that effect). The defenders sing hymns and prayers.

On 2 April, 100 defenders attack the British in a surprise night attack, while others escape towards the swamp. The army pursues them (16 British/150 Maori killed). The British bury the Maori dead. The King Maori and Chief Rewi retreat south to Te Kuiti. This force of the King Maori resistance is finished. Rewi retires from war, eventually works for peace, and dies in 1894.

The British soldiers are very moved by what they have seen at Orakau. “Does ancient or modern history, or our own rough island story, record anything more heroic?”. The Rewi Maniapoto Memorial and Reserve including gateway, monument and Rewi’s grave and tombstone, is later erected at nearby Kihikihi. Soldiers who served in the Waikato Campaign are given land grants at Cambridge, Hamilton, Kihikihi and Pirongia. The King Maori are scattered and reduced in number, but they are still fighting.

Tauranga, Bay of Plenty, 28 April-May, 1864

The government lands 1,700 soldiers and 15 cannon at Tauranga to attack the 230 King Maori there. The King Maori build a fort at Te Ranga, 16km inland from Tauranga harbour, and a road to it “so that the soldiers would not be too weary to fight”. But the British do not attack Te Ranga, so the King Maori build another fort, The Gate Pah, closer to the coast.

The British surround The Gate Pah, bombard it with artillery, and assault it; but the King Maori escape in the night. When the British enter the fort the next day they find that each wounded British soldier inside the fort has been provided with a small water vessel. The King Maori retreat to Te Ranga (35 British/20 Maori killed).

The British bombard Te Ranga, assault it, and take it (10 British/108 Maori killed). The rest of the Tauranga King Maori eventually surrender. This force of the King Maori resistance is finished.

Some 200 prisoners from Tauranga are taken to Kawau Island north of Auckland to build a new settlement; but they escape to the mainland and are found camped on top of a hill to the north at Big Omaha (10 September 1864). They refuse to leave. The government doesn’t know what to do with them. Some leave when offered land. Others leave and go north. By April 1865 they have all left on their own accord. The Maori King retires to Te Kuiti. The King Maori never recover.

More land is granted at Tauranga to soldiers and settlers. British troops begin to be withdrawn from New Zealand. By 1866 only one regiment remains. The capital is moved from Auckland to Wellington (1864). A ship carrying government records and civil servants to Wellington sinks. The records are lost, but the civil servants are saved. The government begins building another road from Wanganui north to New Plymouth. Another road, another campaign.

The Hauhau Campaign 1864-1867

With the King Maori movement quiet, the government begins to think that armed Maori resistance is over. It isn’t. There are still several more uprisings to go. Not a Maori monarchy this time, but new Maori religions.

One day in 1862, a Maori from south Taranaki claims to have had a vision from the Angel Gabriel, telling him that the Maori of New Zealand are one of the lost tribes of Israel (one of the very well lost) and that he should form a new religion “to smite the white turnips and all unfaithful to the Maori King”. So he does.

For joining his new religion, all his faithful followers will be protected by angels and invincible to bullets, provided they shout the religious chant “hau hau” (up, up) with an upraised right hand before charging into the enemy’s guns (“you can shoot and cuss, we are invincible, bullets bounce off us”). All those that the bullets do not bounce off of will only have shown the angels that they were not faithful enough. The religion and its followers will come to be known as the “Hauhau”.

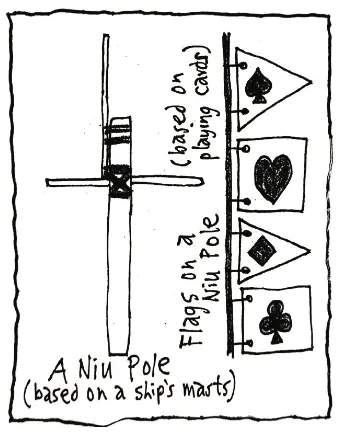

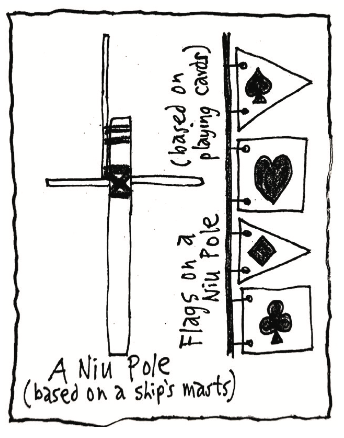

The Hauhau’s religious symbol is the “Niu Pole”, a tall pole with two cross arms at the top representing the calling of the warriors from the four points of the compass to join the fight against the white turnips. Flags are also flown on these poles with symbols on them taken from playing cards (clubs, diamonds).

The BFD. Illustration by Inkblot

The Hauhau also use two particularly devious tricks when fighting the British. They fly a white flag, with a small red flag in the corner of it. From a distance it looks like a white flag of truce or surrender, but when the British approach peacefully, they’re ambushed. Ha ha say the Hauhau. They also wear captured British uniforms and badges, again to deceive the British into thinking they’re Loyal Maori and not the enemy. Ha ha say the Hauhau. But then the Maori did this sort of thing all the time when fighting each other. Trickery and deceit are just part of war. Get used to it. The British do.

The Hauhau attack government soldiers at Nukumaru near Wanganui, drink the blood of a dead soldier, cut off his head, and take the head on a tour of the North Island looking for converts to the cause. Charming.

A ship is attacked by 300 Hauhau at Opotiki, Bay of Plenty. A missionary is hung, decapitated, and his eyes eaten by a Hauhau priest. War dances are then held in the local Catholic and Protestant churches. The Hauhau are not your average boy-next-door.

But at the same time as the Hauhau are gaining some fanatical followers, they’re also causing more Maori to reject them, to work to persuade others not to join them, and to join up themselves with the government forces to fight against them (now mainly New Zealanders as most of the British soldiers have gone).

Government forces attack the Hauhau at Opotiki, Pipiriki, Patea and Moutoa Island (Wanganui River); and the Hauhau retreat to their fortress at Weraroa on the Waitotara River (nr. Wanganui).

Weraroa, 17-22 July 1865 – Weraroa is a well-fortified position on the top of a steep precipice, with the river behind and rifle-pits and palisades in front. A combined force of 309 Loyal Maori and 164 New Zealand Militia encircle the fort defended by some 200-600 Hauhau, and offer peace terms. The Hauhau reject them. The attackers launch ambush raids by night, and snipers pick off defenders by day. The fort is taken when it is abandoned by the Hauhau at night. Thanks to the Loyal Maori tactics not one government soldier has been killed (the British would have just assaulted the position and taken casualties as a result).

The Hauhau attack Whakatane and Wanganui. The government captures Opotiki aided by Maori from Rotorua (September 1865), and the Hauhau retreat inland to Rangitaiki near Lake Taupo. Government troops follow them. At Rangitaiki the Hauhau have constructed a fort on a rise beside a river with three lines of palisades and rifle-pits, flanking firing angles, earthworks, fortified huts, and a covered escape route to the river. But after the government forces tunnel for two days towards the fort, the Hauhau surrender rather than be blown up. The government takes 30 prisoners and the Rotorua Maori take the rest (the 30 government prisoners were the lucky ones).

The Hauhau are scattered and hunted down at Tokomaru and the Waiapu River, East Cape; Pukemaire and Kawakawa, Northland (500 captured); and Waerengaahika, Poverty Bay (August-November 1865).

In early 1866 a force of 986 government troops(including 286 Loyal Maori) under General Trevor Chute, sets out on “Chute’s March”. They go from Patea (south Taranaki) to New Plymouth (north Taranaki) and back in a counter-clockwise route around Mount Egmont; attacking seven Hauhau fortresses, destroying 20 Hauhau villages, and capturing the founder of the Hauhau who later renounces Hauhauism as “a delusion under which I fancied myself inspired”.

Chute’s March crosses 21 rivers and 90 gullies, is welcomed back by the band of the 18th Royal Irish, but “left more enemies in the district than they had found”.

More land is given to settlers and soldiers at Opotiki and Tauranga, Bay of Plenty; and from the Waitara River in north Taranaki to the Waitotara River in south Taranaki; and in June 1866 a dispatch is sent to Britain reporting that “the island was at peace”. Only it wasn’t.

There are still Hauhau in Hawke’s Bay. A force of 125 of them plan to attack Napier, but as they are dancing around their Niu Pole at night at Omarunui (near Eskdale north of Napier), they are surrounded and given one hour to surrender. The Hauhau think one hour is not enough time, so they are given two hours. After two hours they are told they will be given no more time, to which they answer: “There is no reason to do so as we mean to fight” (3 British/27 Maori killed, 76 Hauhau taken prisoner).

The last remnants of the Hauhau are captured at Onepoto on Lake Waikaremoana, Urewera, and 400 prisoners are sent to the Chatham Islands “not one escaped from us” (at least not yet). One Hauhau chief surrenders because “inflammation has damaged my right eye, and as I can no longer shoot properly I could not shoot anybody”.

The situation on the North Island of New Zealand in 1867 is that the country is in “a doubtful armed truce”. It also suffered from what weary British Secretaries of State called “memorandummiad”. New Zealand has wars not only with guns, but with paper too.

There are Indemnity Bills, libel and sedition trials, Native Land Acts, Native Rights Acts, Native Land Courts, land assessors, Compensation Courts, Public Works Land Acts, Outlying District Acts, Settle- ment Acts, Native Commission Acts, Native Reserve Bills, Police Bills, Land Claims Commissions and Native Land Purchase Ordinance.

Lots of paper. Lots of government. New Zealand history is complicated.

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand from Amazon today.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.