Table of Contents

18th March 2021

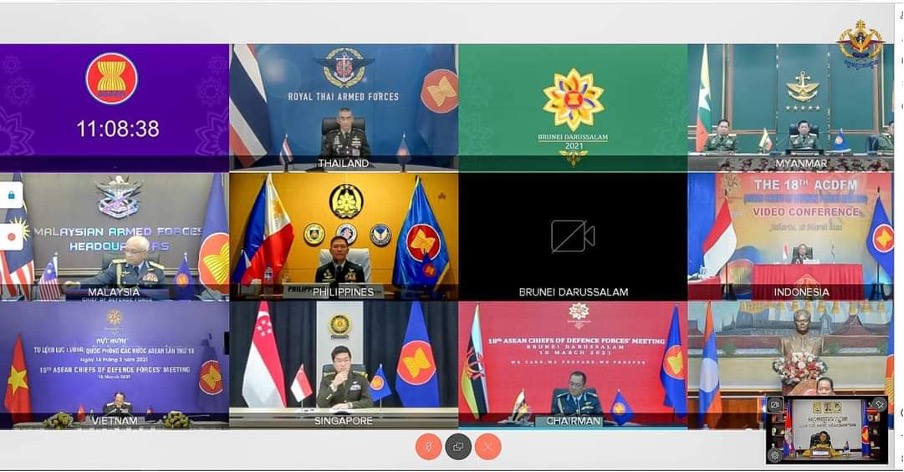

The 18th ASEAN Military Intelligence Meeting AMIM-18 took place online yesterday morning.

The meeting was attended by Lt-Gen Ye Win Oo, Colonel Haji Mohammad Muluddin Bin Awang Haji Latif of Brunei, Lt-Gen Hun Manith of Cambodia, Maj-Gen Andjar Airatma of Indonesia, Maj-Gen Thongvanh Chanthavong of Laos, Lt-Gen Datuk Ahmad Norihan Bin Jalal of Malaysia, Brig-Gen Charlton Sean Gaerlan of the Philippines, Brig-Gen Ng Chad-Son of Singapore, Lt-Gen Natee Wongissares of Thailand and Lt-Gen Pham Ngoc Hung of Viet Nam.

General Min Aung Hlaing also attended online.

First, alternate chair of 18th AMIM Brunei’s Colonel Haji Mohammad Muluddin Bin Awang Haji Latif made an opening remark.

Then, the meeting exchanged view on the theme “We Care, We prepare, We Prosper”. (Yeah, Right)

They also discussed the exchange visiting of ASEAN junior intelligence officers and establishing the ASEAN Military Intelligence Community.

The meeting was concluded after the 19th ASEAN Military Intelligence Meeting’s chairmanship was handed over to Lt-Gen Hun Manith of Cambodia.

Source Global New Light of Myanmar 18th March 2021.

I hope they all had a jolly good time; I would think that the situation in Myanmar wasn’t raised, but they just had a wonderfully delightful chat about procurement, the exchange of intelligence probably being one-sided.

It has been alleged that the military started a blaze (conflagration?) that wiped out an Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp last night. The camp situated in Tein Nyo in northern Rakhine was literally burnt to the ground.

After last night the Current Situation of Tein Nyo IDP Camp burnt during the night of 17 March 2021 is as follows:

- Houses destroyed – 663

- Affected Population – 2565

- Original number of Houses – 875

- Original Population – 3355

Everything was burnt except for the clothes on their backs. The effect is that the homeless are now even more homeless. I can’t trace whether the shortfall in residents is because they left prior to the fire or not. I assume that they have gone away.

The double homeless with their possessions.

The fire allegedly started by the military.

The fire at its height.

Even by the standards of the Tatmadaw this is some achievement. I am surprised that pictures and information managed to get out of the country. Perhaps it’s because the Tatmadaw are brazen enough to not care about the world image anymore, they are enjoying it too much to bother about censoring it.

As an aside, in 2012 the ongoing administrative reform in the Myanmar Police Force (MPF) included adoption of community-based policing as the main philosophy of the police department.

To avoid some of the consequences of protest and confrontation, the protestors are advocating a new weapon to use against the military.

Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement against military rule has come to take many forms, including a strike by government workers, mass street protests and a public boycott of military-linked businesses. But in recent weeks, a new front has opened in the struggle: a “social punishment” campaign against the families of senior members of the regime.

People have been using social media to identify the relatives of the military generals, announcing where they live, what they do for work, and what foreign universities their children attend. They then urge people to shun and shame the individuals, and to boycott their businesses.

Activists have also targeted generals’ children who are attending schools and universities abroad, urging both Myanmar expatriates and the natives of those countries to ostracise these students.

Ma Nan Lin Lae Oo, a student of Japan’s Toyo University, is the daughter of General Kyaw Swar Oo, who activists say is responsible for the fatal shootings of peaceful protesters in Mandalay – including 19-year-old Ma Kyal Sin, who has become Myanmar’s most celebrated pro-democracy martyr since her death on March 3. They have called online for the university to revoke Nan Lin Lae Oo’s scholarship, and for the Japanese government to rescind her visa.

These social punishment efforts have been potent, prompting some who’ve been targeted to close their Facebook accounts and keep a low profile.

In ordinary circumstances, the campaign’s tactics would probably amount to cyber-bullying, or at least to flagrant invasions of privacy. But these are no ordinary times, and while the ethics of the campaign are open to debate, they must be understood in the context of Myanmar’s long, dark history of military rule. For some former political prisoners and veteran pro-democracy activists, who suffered their own forms of social punishment under the previous junta, the campaign is a form of retribution.

These dissidents were not only imprisoned for years and tortured; after being freed, both they and their families were deliberately marginalised, such that they were often unable to reintegrate into society or advance themselves. Family members in the civil service were dismissed or denied the opportunity for promotion. They were also denied passports, meaning they could not flee abroad, and Military Intelligence pressured school headmasters to not accept their children. Teachers were also urged to discriminate against these children, and their classmates were warned not to interact with them. This ostracism persisted for decades.

Meanwhile, generals and those in their circles, enriched by various forms of corruption, were able to send their children to elite schools and universities abroad. When these children returned home, they often used their parents’ connections and the riches they had looted from the public to establish large businesses in Myanmar.

In contrast, the children of most Myanmar citizens are denied a proper education or economic opportunities, and often end up working for companies owned by the generals and their allies. They feel enslaved to a ruling class of military families.

Now, the people of Myanmar – through the boycott of military goods, acts of civil disobedience and the social punishment campaign – are fighting back. Myanmar Buddhists view the public shaming as karmic retribution for the generals’ evil deeds.

In a just society, no child should have to pay for the sins of their parents, but this campaign is the natural product of decades of injustice and resentment. This harmful legacy can only be overcome if military dictatorship ends, and democracy and human rights are allowed to flourish in Myanmar.

Source the Irrawaddy 18th March 2021.

It will be interesting to see where this takes us. It will work well in metropolitan Myanmar but may be limited in its impact in the country districts.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD