Table of Contents

Australia has quite a track record for royal commissions. In just the 120 years that they’ve been legislated, we’ve had no less than 139 of them — and that doesn’t count the state-based ones. Everything from the butter industry (1904-05) to bushfires (2009) and institutional child abuse (2013-17).

Royal commissions are most frequently set up in response to disasters and public malfeasance by authorities.

So, it would seem natural to establish a royal commission into the conduct of pandemic policy in Australia. Oddly, though, only one maverick voice in Australia’s parliament seems even remotely interested in doing so.

Pauline Hanson has called for a royal commission into how Australia’s governments have handled the COVID-19 pandemic.

The One Nation leader says whichever party forms government after this year’s federal election there should be an honest and thorough examination of how all governments – federal, state and territory – managed the crisis.

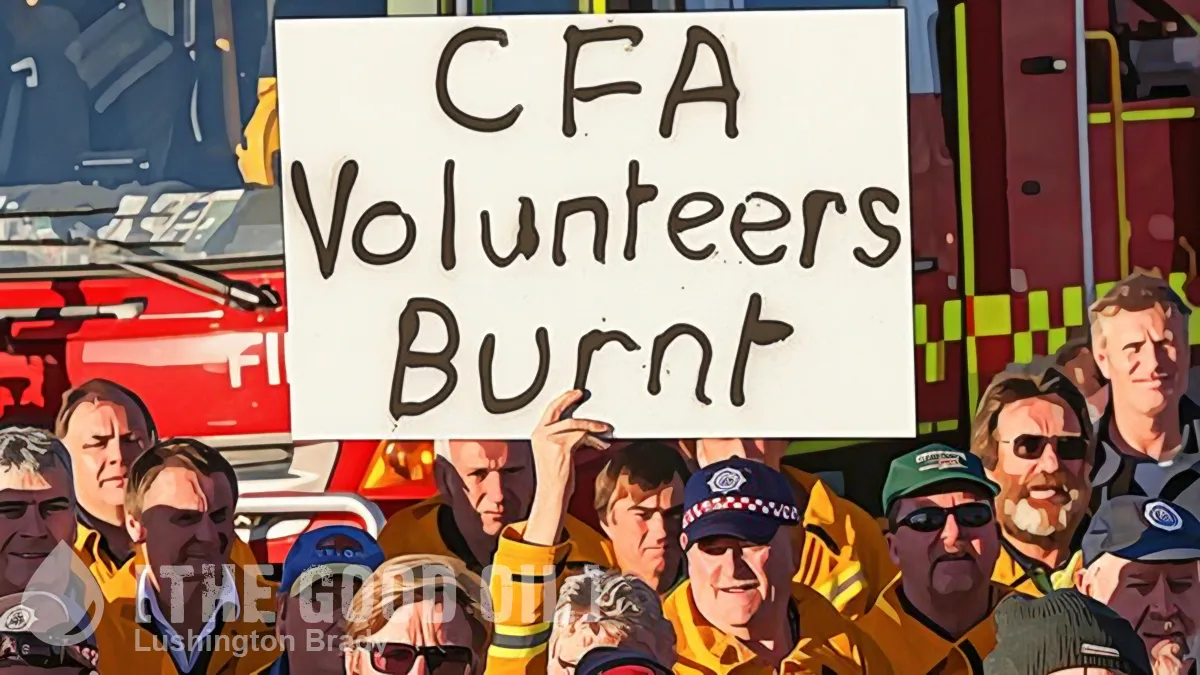

Hanson is absolutely correct that the pandemic has been a disaster for Australia. Often because of, not in spite of, the measures imposed by governments and their public health bureaucracies.

She says the pandemic has affected every Australian in some way with people dying, workers losing their jobs, individual rights and freedoms being restricted and unelected bureaucrats wielding ‘extraordinary power’.

‘We need a royal commission, not to lay blame or find scapegoats – the buck will always stop with the prime minister and state and territory leaders, as it must in a representative democracy,’ she said.

Daily Mail

And that’s exactly why it’s unlikely there’ll ever be one into the pandemic.

Royal commissions are the highest form of governmental inquiry, with often extraordinary investigative powers, including compelling testimony and seizing documentary evidence (even protected documents like government papers). Which pandemic politician in their right mind is going to allow that?

Ultimately, even a royal commission is much like any other government inquiry: never set up an inquiry unless you know in advance what its findings will be. In the case of a legitimate royal commission into the pandemic, a good many powerful figures know perfectly well what its findings might be.

Which is just why it will almost certainly never happen.

Think about what a genuine royal commission would look into:

- Why already-developed pandemic plans were scrapped, and whose decision was it?

- Who decided that the federal government, contrary to established precedent, wouldn’t join Clive Palmer’s High Court challenge to the closing of state borders?

- Are there any conflicts of interest between any of the covid decision-makers (politicians or health bureaucrats) and the pharmaceutical industries?

- Why were routine medications suddenly banned from off-label prescription?

- Where is the actual evidence that health bureaucrats used in imposing lockdowns and curfews?

- How accurate was covid-modelling, after all?

- How many Covid-registered deaths in Australia were “from” Covid and how many were “with” Covid?

- Is coerced or mandatory vaccination legal under Australian and international law?

Yeah, I don’t think they’re going to want to answer those questions, either.

But, given that royal commissions and their terms of reference are set by the government of the day, it might actually be a smart political move for PM Scott Morrison to set up a royal commission on his own terms, before the election. A royal commission designed to conveniently minimise federal issues would be a juicy stream of dirt against the Labor governments in WA, Queensland and, especially the golden goose, Victoria.

Machiavellian, maybe, and still extremely unlikely.

Because royal commissions also sometimes go off the plantation. The Fitzgerald Inquiry in Queensland, into police corruption under the Joh Bjelke-Petersen government, was clearly intended as a damage-control measure by a panicked deputy premier, after damaging tv allegations were aired while his iron-fisted boss was out of the state. The inquiry quickly snowballed out of the government’s hands, and within six months, Bjelke-Petersen was dumped as premier and eventually only narrowly escaped a perjury conviction and jail time.

Somehow, I can’t see any current Australian politician taking that kind of risk.