Table of Contents

On Mike Hosking’s show on Tuesday, Jacinda didn’t answer a single question. She still seems hellbent on delaying and obfuscating as much as possible. Grant Robertson denies everything. It is a total brick wall.

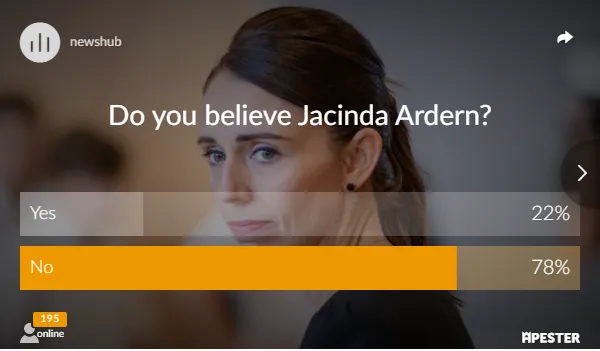

But why are they doing this? Wasn’t a Newshub poll last week, where 80% of voters said they did not believe her, enough for Jacinda to realise that we have all seen through this?

David Farrar at Kiwiblog has some answers.

Anyone who thinks the PM’s senior staff and Grant Robertson were not meeting regularly over at least the last six weeks on how to deal with this scandal is naive. I know these people. There is no way they were not dealing with this issue as a priority.

So Farrar thinks they all knew about it; so Jacinda’s claims that she did not are therefore untrue.

The real question is why didn’t they decide the staffer had to go six weeks ago when this went public, or even in the months before that as they learnt about the complaints. The same applies to why the labour Party Council went with a process that seemed design to exonerate the staffer .

If this guy was the office clerical assistant, he would have been gone months ago. Doesn’t matter about proving the complaints – the mere fact 12 people have complained means you’re become a liability.

At the point the complainants went public, it would be an absolute no brainer. You have a choice of a scandal that affects your core brand involving the Labour leader, President, Finance Minister and NZ Council. the point when four of your own Ministerial staff have gone to Paula Bennett because they are so horrified Labour have taken no action, the decision is not just obvious but overwhelming.

Unless there are reasons why Labour were prepared to risk all this damage for this staffer.

The accused had lawyered up, obviously. Maybe he had threatened everyone with a lawsuit if even a hint of scandal was attached to him?

Trouble is, I don’t think that works. Safety in the workplace for all staff is still paramount, surely?

This was beyond doubt a deliberate decision by the Labour decision makers that this staffer would be protected. Because otherwise he’d have been goneburger months ago.

And David Farrar’s conclusion is:

This was Labour making a calculated decision that they would try and brazen this out, because he had the right friends, and was so valuable to them in his job. The impact on the complainants and victims was a secondary or even tertiary factor.

Just imagine if he was not a party office holder, was not mates with senior Ministers and did not hold a critically valuable role in terms of targeting information to voters. Do you really think he wouldn’t have been goneburger months ago after 12 different people complaining about you?

Interesting. Simon Wilson, at our favourite newspaper, has some other ideas to add.

How does an organisation committed to social justice, its ranks full of feminists, not know how to do the right thing when presented with allegations of sexual abuse by one of its own?

Perhaps the officials believed the person complained about was a valuable, upstanding party worker. That might make them inclined to assume the problem was smaller than it really was.

Again, did the Party want to protect someone important to them, even if he had committed a crime?

If you’re in a political party and it’s drummed into you that the priority is always, always, to build the credibility of the party so you can win the next election, your instinct, which you trust, is to bury problems.

The Party is more important than anything. Didn’t Joseph Stalin once say that? Or was it Mao Tse Tung?

When an employee complains it’s likely the focus will be, not on addressing the cause of the complaint, but on shutting it down. Often that means removing the complainant, with the minimum possible payoff and a non-disclosure agreement to keeps things tidy.

Which is what was happening, of course, until those pesky victims went to Paula Bennett and eventually to The Spinoff.

In politics, this gets ramped up because they’re on a wartime footing. The first and last thing they say when anything goes wrong is, if this gets out the opposition will use it to try to destroy us.

In politics, particularly on the left, the social-democrat side, there’s another factor. They’re on the side of the angels. They believe they’re making the world a better place.

I wonder if the victims of this very valuable staffer think that Labour are making the world a better place?

But believing you’re the good guys has a downside. It tempts you to attach a moral imperative to everything you do, even when it’s undeserved. The means, perhaps, justify the end. The bigger picture is more important than your little problem. You have to suck this up for the good of the party. We can’t be the bad guys, because, remember, we’re the good guys.

And there you have it. Either this staffer was so valuable and well connected that Labour was going to die in a ditch supporting him, or they acted for the ‘good of the party’, even if it was to the detriment of a particular individual. This is fantastic insight from Simon Wilson.

Personally, I think both theories are true. The alleged perpetrator was a high-ranked official within the Labour Party. Also, Labour, led by Jacinda with her mantra about kindness and wellbeing, think they have the moral high ground in everything. Everyone must act for the benefit of the Party. If there is collateral damage along the way, what does it matter? The greater good is all that counts.

The ‘collateral damage’ in this case fought back. Now Simon Mitchell claims he never received email attachments detailing sexual abuse from the victim. Mitchell is a lawyer and a member of the Labour Council that decided that there was no case for the staffer to answer. He is also the person who paid $5,000 to buy the painting that then PM Helen Clark signed. Conveniently, the fraud claim against her went away after it was discovered that he had destroyed the painting…oops. Were his actions back then for the ‘good of the Party’? And now?

Yes they were. This staffer was too important to lose. For the good of the party, he had to be retained. Jacinda, Grant Robertson and Nigel Hayworth believed they could just dig in and make it all go away.

They were wrong.