Table of Contents

Peter Jacobsen

Peter Jacobsen is a Writing Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education.

In the 2020 election, an interesting candidate made his way onto the scene for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination: Andrew Yang. Yang made a splash in particular for his promise to give everyone $1,000.

Andrew Yang’s campaign strategy took a similar approach to Trump’s 2016 campaign in hyper-focusing on a single issue. For Trump, the single issue was immigration. For Yang, that issue was universal basic income (UBI).

Yang’s version of UBI was alluring in its simplicity. Every person in the country would receive a nice, round $1,000 per month. It didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, old or young. A vote for Yang was a vote for cash.

Many from his own party denounced the idea of giving rich people $1,000 per month. But Yang held strong to the payment being universal. By making sure every person gets $1,000, you avoid some incentive issues and the bureaucracy that accompanies typical welfare programs.

Why UBI?

Why have a UBI at all? Yang gave several reasons. One primary concern Yang had was that technology would soon begin to displace many low-skilled jobs. UBI would help the country get ready to take care of displaced workers.

But Yang claimed a myriad of benefits for UBI beyond just a safety net. UBI would free people up to be creative and entrepreneurial. A guaranteed income would provide people with the security they need to pursue their passions, start businesses, or go back to school. Contrary to the claims of detractors, a UBI wouldn’t increase laziness – it would improve people’s productivity!

Sometimes, UBI supporters even highlighted how it would make government smaller if it replaced our current complicated welfare system. Though, to my knowledge, no advocate of this policy has ever explained a realistic path toward abolishing current welfare programs.

So, is Yang right? Would UBI free the inner entrepreneur in all Americans, or would it just mean some people would engage in more leisure? Let’s look at the evidence.

The Disappointing Basic Income Study

Researchers Eva Vivalt, Elizabeth Rhodes, Alexander W Bartik, David E Broockman, and Sarah Miller’s working paper, titled “The Employment Effects of a Guaranteed Income: Experimental Evidence from Two US States,” was recently put out by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

The study “leverag[ed] an experiment in which 1,000 low-income individuals were randomized into receiving $1,000 per month unconditionally for three years.” What were the results?

First, it made the recipients poorer: “Overall, the transfers led to a reduction in annual total individual income of about $1,500 in our main survey measure, compared to the control group.” Why? Well, people worked less (1.3 hours per week less) and stayed unemployed for longer! Not only do the recipients work less; this happened to other adult members of the household as well.

Unemployment duration “increased by 1.1 months” for recipients.

But did people use this time to find a better job? It doesn’t seem like it. Recipients appear to be more selective in their applications, but the authors say, based on their survey measurements, “We do not see much in the way of differences in the types of jobs participants applied for,” and “the results do not support any changes in quality of employment.”

Were people doing other productive things in unemployment, though? The results are unimpressive.

The authors examine whether the receipt of basic income increases entrepreneurship. While they find people claiming to have more entrepreneurial intention, this does not translate into actual entrepreneurial activity.

What about education? Do people go back to school? Mostly no. The authors say, “By and large, we do not observe significantly improved education outcomes in our sample, though there are some indicators of minor improvements.”

So what did people do with the extra time they got from working less?

In short, the answer is, they relaxed.

In concluding the results of the paper, the authors say, “[P]articipants in our study reduced their labor supply because they placed a high value, at the margin, on additional leisure.”

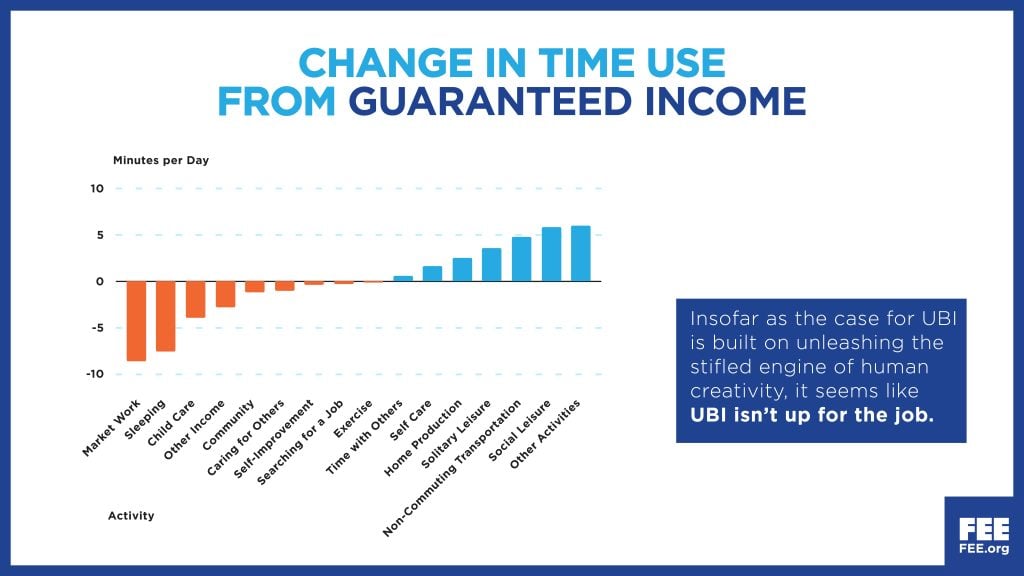

The authors provide an even more in-depth breakdown of time usage from their study. They estimate the number of minutes per day allocated doing different activities. The figure below gives a breakdown:

The results? Well, apart from the “other activities” category, the biggest increases in time were non-commuting transportation, social leisure, and solitary leisure. Some time was also spent in home production (doing work around the house) and “self-care.”

On the flip side, people spent less time working, sleeping, caring for children, generating income, and engaging with their communities. Furthermore, less time was spent on self-improvement, searching for jobs, and exercise.

The numbers here may seem small, but if you apply this to millions of people daily, it becomes very weighty.

Not all of the results were statistically significant, but the major point is, overall, people used the time they gained from working less to engage in leisure, and there is no evidence of an increased use of time in other categories UBI proponents purport to care about, such as creative output, entrepreneurship, community engagement, self-improvement, or even spending time with children.

Where does this leave UBI advocates? Well, at best the evidence shows a UBI would cause people to work less and relax more. Insofar as the case for UBI is built on unleashing the stifled engine of human creativity, it seems like UBI isn’t up for the job.

This article was originally published by the Foundation for Economic Education.