Table of Contents

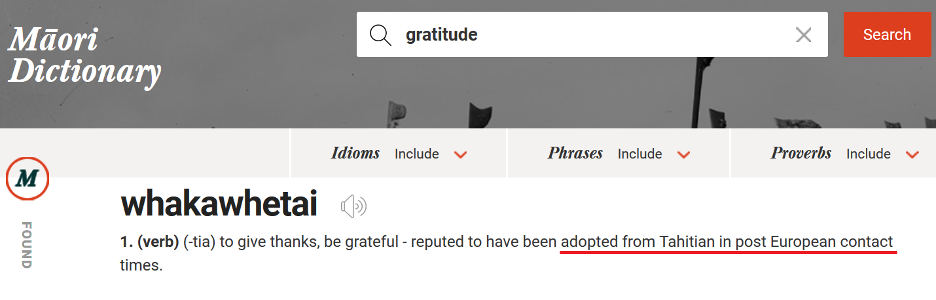

As ‘Maori Language Week’ comes to a close I thought it appropriate to bring you the reo for ‘gratitude’, but such a word does not exist in the tongue. Did you know that?

To understand why we need to hear from the brilliant Mr William Colenso, a prolific publisher in Te Reo, a man with deep knowledge of the people and language, and a mind (like many others of his era) bent towards life-long philosophical and anthropological enquiry. From his excellent essay “On the Maori Races of New Zealand” preserved in the very first volume of ‘Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand’ published 1868:

“There is still one more glaring vice of theirs to be noticed, namely, ingratitude. This, it must be confessed, did everywhere exist, and that to an extent almost unheard of elsewhere. To a New Zealander gratitude was wholly unknown. They have no word for it in their language; no way of expressing such a feeling, which never existed in their breast. To a deeply reflecting mind, this sad fact may appear to be a far worse one than their cannibalism. There can be little doubt but that their total want of this high feeling of the soul, arose from their own peculiar natural condition; particularly from the fact, that no New Zealander ever did any kindness, or gave anything, to another, without mainly having an eye to himself in the transaction; and this was known and reciprocated. Of all their characteristic vices, this of ingratitude appears to be one of the worst.”

Which point I raise not to denigrate the people of Maoridom, far from it, for to do so would be to denigrate my own children, and grand-children – my moko – and neither did Mr Colenso write it with such intent, indeed the forthright scholar concludes his remarkable piece (which, in my opinion should be required-reading in the nation’s schools):

“The writer of this Essay has no hesitation in expressing his settled conviction; that, (apart from any spiritual Christian benefit,—a subject he has generally throughout this Essay carefully avoided) taking all things into consideration, and viewing the matter from a philanthropic as well as a New Zealand point of view,—it would have been far better for the New Zealanders as a people if they had never seen an European.”

My reason for bringing these words is to highlight that which is missing from the contemporary academic-driven cultural relativism and revision taking place before our very eyes: honesty, pono, straight-forwardness, a quality seemingly discarded by the modern ivory-tower set, a blindness, such an undersight unthinkable to doyens past, as foreign to 19th-century scholarship as gratitude to pre-European Maoridom.

Mr Colenso had words of advice and scorn in equal doses for those of his contemporaries considering themselves passable in the language of these isles. Lord knows what contempt he may have held for the media-luvvies of the 21st century’s practised micro-pitches in reo self-congratulatory narcissism. Of such plastic-tiki-talkers Colenso commented:

“It is also remarkable how very soon natives get to know the true mental calibre of a white man; to gauge, as it were, his knowledge of their language and of themselves, and to say and act accordingly.”

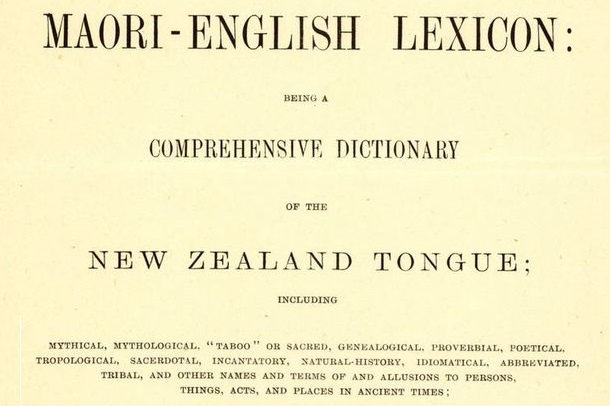

Charged by the colonial government with producing the authoritative lexicon of the Maori language Colenso set himself a job impossible by one man in a lifetime, but confidently predicted, in 1865:

“The plan or prospectus is simply a Maori-English and English-Maori Library Lexicon to contain every known word in the Maori tongue with clear unquestionable examples of pure Maori usage, and with copious references (as far as known) to the principal Polynesian Dialects to be completed in say two volumes … the ‘time’ required for the whole work – to do it satisfactorily – cannot well be estimated at less than seven years.”

The work expanded in scope as time went on and was never to be completed, a glance at the title page will give a glimpse as to the reasons why:

More than thirty years later, at the intervention of his death, only the entries for ‘A’ had been published. It was his “great disappointment.” The sample tome is nevertheless worthy of study for the depth of research and breadth of knowledge on display. And as for the essay mentioned in opening; it is an excellent piece of reading for anybody interested in New Zealand history. Colenso does employ some speculations, clearly stated, but not without sound reasoning, and you’ve got to admire a man that judged these islands had to have once been a large continent, now submerged, a ‘fact’ confirmed almost exactly 150 years after Colenso first conjured the probability.

It’s a work worthy of your precious time.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.