Table of Contents

Giselle Bastin

Flinders University

Giselle Bastin has a BA from the University of Adelaide, and a PhD from Flinders University. I am an Associate Professor in English at Flinders University.

Warning

Long read. 2036 words.

Those of us interested in biographies of the House of Windsor have awaited Tina Brown’s The Palace Papers with much anticipation. Her 2007 book, The Diana Chronicles, was a New York Times bestseller, cementing Brown’s reputation as a royal biographer exemplar.

A former editor-in-chief of Tatler, Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker, in 2000 Brown was awarded the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II for her services to journalism.

Review: The Palace Papers: Inside the House of Windsor – the Truth and the Turmoil, Tina Brown (Century, 2022)

Brown’s authority to tell the story of the last 25 years of the House of Windsor is signalled clearly in the book’s 10-page acknowledgements section, where every royal biographer, historian and media commentator A-lister appears as a source.

The endorsement on the book’s front cover from Lady Anne Glenconner, one of Princess Margaret’s closest friends, offers a double whammy in one short statement: “Tina Brown has inside knowledge and writes well”. These are the very two things lacked by so many popular royal biographers — genuinely good contacts and writerly panache.

Many of Brown’s sources are so impeccable and well-placed she can’t even name them:

There are so many who helped make this narrative more accurate, more fair and more honest but whom, because of ongoing or intimate past relationships with the Palace, I cannot name or thank.

Her book paints a complex picture of how the royals and their scandals from the late 1990s to the present day have been amplified from without by a sinister network of media attackers, who with their stings and exposés, mounted a constant and stealth-like attack on the royals’ privacy.

It offers a portrait, too, of how the family’s woes have been orchestrated and amplified from within by a series of press advisers — (including Mark Bolland, aka “Blackadder”, Prince Charles’s Deputy Private Secretary from 1997-2002) — who used their respective press offices in Buckingham Palace (the Queen and Prince Philip), St James’ Palace/Clarence House (Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall) and Kensington Palace (William and Catherine, and prior to 2019, Harry and Meghan) to jostle for media exposure and control of the royal narrative.

A picture emerges of a family that does what all families do, i.e. gossips about one another, but also briefs against each other.

Brown recalls how “during the so-called War of the Waleses”, Charles’s camp did as much backgrounding and leaking as Diana’s via the tabloids they both professed to hate. “Charles spun furiously; he was just less good at it”.

And “whatever the high-minded stance towards the vulgarity of publicity”, the competing press offices are still at it today:

There is an unwritten rule that they will not step on one another’s media moment in deference to the royal hierarchy … though in Prince Charles’s case, new bombs from outlier family dramas have a habit of exploding whenever he is about to step up to a podium.

The Palace Papers offers a glimpse of the intersection of “prime ministers, influential courtiers, powerful spin doctors, lowly hangers-on, lovers, rivals and even outright enemies” in the royal drama, although it is often uncertain which individuals are the powerful spin doctors (the press officers or some of the royals themselves?), or the hangers-on or even the “outright enemies”.

The fact that tales about royal shenanigans so often blur these boundaries makes for some entertaining reading.

Too much complaining, too much explaining

Perhaps the royals themselves, in their efforts to curate their own publicity, are shown to create the greatest threat to the Windsors’ long held mantra of “never complain, never explain”.

The key transgressors in this regard were the late Diana, whose “going on the record” revelations about life as a royal set the pattern for the royal whinge-fest of the next 25 years, as well as Prince Harry and Meghan Markle who are laid bare as the most desperate and ill-judged architects of their own fumbling narratives about feeling miserable, misrepresented, and misunderstood.

Brown doesn’t add any startingly new revelations about Harry’s and Meghan’s move away from the royal family but she chronicles the saga of their discontent and eventual exile from the royal fold in the same considered and reflective way she captured the Diana years.

In the period immediately after Harry’s and Meghan’s wedding,

There was a histrionic (even hysterical) quality to the way the Sussexes declared they wanted to be private. A desire for privacy is understood (if not respected) by the media; an obsession with secrecy is not, particularly when combined with high-profile socialising.

The key to being private in the Royal Family, she writes, “is to truly — not performatively — want to be so.” Ouch.

She says of Meghan in particular:

[S]he couldn’t wait to cram down every cake offered on the celebrity buffet … An invitation from Elton John to fly private to his South-of-France villa just two days after a sun break in Ibiza to celebrate Meghan’s 38th birthday? Two big slices please! A hop back to the US Open in New York to watch her pal Serena play [tennis]? Yummy, yummy!

The Sussexes’ dummy spit and royal exit reached its climax, Brown claims, when they noticed their family portrait — so prominently on display at the Queen’s elbow during her 2018 Christmas broadcast — was missing in the 2019 line-up of family photos.

The Queen told the director of the broadcast that all the displayed photographs were fine to remain in the shot except for one. Her Majesty pointed at a portrait of Harry, Meghan and baby Archie. ‘That one,’ said the Queen. ‘I suppose we don’t need that one’.

The Queen’s no nonsense approach to dispatching troublesome family members (although not her son, Andrew) is captured in another anecdote told by a top royal courtier about how the scene in Stephen Frears’s 2006 film The Queen, where the monarch shoos away a noble stag (symbol of Diana?) before it can be hunted down, is highly inaccurate. Far from acting as the stag’s protector, he said, “‘The Queen would have shot it’”.

‘Collaborating’

When the Sussexes’ prematurely announced on their website “Sussex Royal” their proposal for a new working model of how they would remain members of the royal family, half-in and half-out, it was the Queen’s turn to have a dummy spit. The declaration that they would continue to “collaborate” with her “as if the monarch were the co-executive producer of a TV series” sent the Palace ballistic.

The Queen, Brown reminds us, “does not collaborate. She commands … as her impetuous grandson was about to find out”. No royal highness status, no royal patronages, no military titles, no publicly-funded security, and no money from the Sovereign Grant.

Brown’s prose can delight in ways that the more plodding printed biographies and low-grade television documentaries fail to do. During the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, for instance,

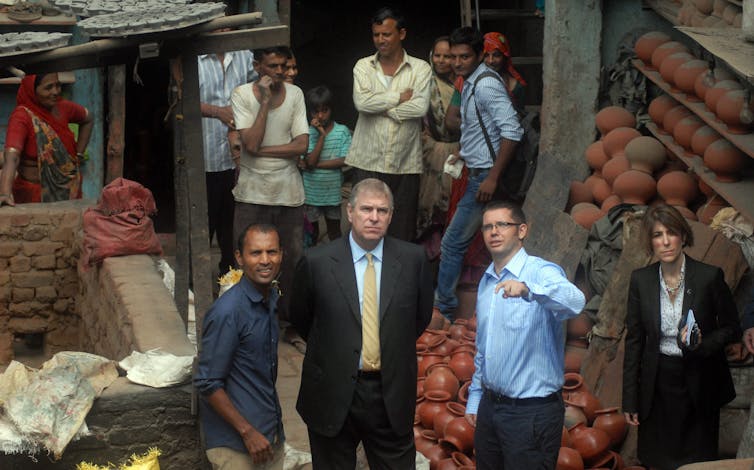

The rest of the family were dispatched on a Commonwealth charm offensive. Charles and Camilla hauled ass to Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. William and Kate, fending off pregnancy questions, were dispatched to Singapore, Malaysia, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands. Prince Andrew, with his usual perfect pitch, took a private jet to visit a Mumbai slum.

And for far too much of his time on Earth, Prince Andrew has proven himself to be “a coroneted sleaze machine”. Brown reports that a visit to the former US ambassador to the UK Walter Annenberg’s house in the 1990s saw the prince, much to the ambassador’s wife’s disgust, “holed up in his bedroom for two days apparently watching porn”.

Of Harry’s and Meghan’s wedding, Brown says: “For the Palace, the kumbaya moment (of the wedding ceremony) was even more remarkable because of the shit-show that preceded it”; and 2019 brought new lows:

While the Duke and Duchess of Sussex went off to implode in a rented $13 million waterfront mansion on Vancouver Island, Prince Andrew, in November 2019, decided to strap on a suicide vest and sit down for an ask-me-anything interview with (the BBC’s) Emily Maitlis.

Gossipy tidbits about the royals appear on every page.

Stories about Philip’s long-rumoured — and always denied — relationships with other women make an appearance.

The writer, John Mortimer, meanwhile, seated next to Princess Margaret at an All Souls College dinner in 2000, is given a glimpse into the old world of royal racism when the princess says:

I do hope my sister will come and stay with me in Mustique … She’s so tired after this ghastly Commonwealth prime minister conference. Every day a different blackamoor crying on her shoulder and you know, she’s so wonderful. She knows all their names!

Après moi, le déluge

The narrative’s pace can be patchy occasionally. A too-long chapter, “Snoopers” that details the News of the World hacking scandals of the early 2000s, serves as a framework in which to understand the royals’ — particularly Harry’s and William’s — deep distrust of the media. But it seems fuelled, one senses, by a personal grudge Brown has for Murdoch’s firing of her husband, the late Sir Harold Evans, as editor of The Times in 1982. It’s an understandable grudge, but a chapter that loses sight of the royal saga.

The Palace Papers, charts the choppy waters of the good ship Windsor as it careens its way towards the inevitable demise of one of the greatest assets the crown has ever had, Queen Elizabeth II. The biography opens with a prologue titled “Kryptonite” and closes with an epilogue, “Embers”, charting the various metaphorical fires, tsunamis, and “hurricane of scandal[s]” that occurred in between them.

After the Queen’s death, predicts Brown,

Amidst the deluge, the tsunami, the engulfing torrent of world mourning, the man [Prince Charles] who has spent seven decades in the waiting room of his destiny will finally walk through its door.

Or perhaps Brown should have said, “cling to his life craft for dear life and hope to alight on shore”.

The non-royal born women — an anchor?

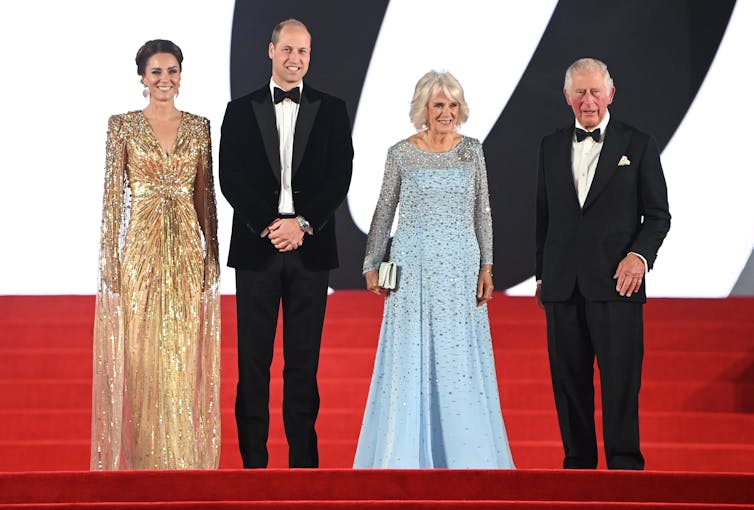

Brown’s thesis is that the non-royal born Windsor women will provide an anchor for the House of Windsor as well as steer a steady course for the institution into the future.

Camilla, Catherine and Sophie Wessex (Prince Edward’s wife) — whose lives have been shaped by their solid, home counties’ middle-class family backgrounds — emerge as the beacons of hope.

The Palace Papers is bookended with the palace edict after the Diana years that “never again” would the institution allow another royal to overshadow the figure of the sovereign.

It seems a real possibility that “Never again” will we witness a reign like that of Queen Elizabeth II’s — a note of genuine foreboding in an otherwise irreverent, delectable and highly entertaining account of the biggest soap opera family on Earth.

Giselle Bastin, Associate Professor of English, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.