Table of Contents

Grant Duncan

Massey University

New Zealand’s election is coming down to a simple contest between the Labour-Green bloc on the left and the National-ACT bloc on the right. Although the right is behind in the polls, if it were to gain the majority, ACT Party leader David Seymour could become deputy prime minister.

Either way, ACT is newly assertive. Although Seymour owes his Epsom seat to National’s grace and favour, he seems less inclined nowadays to be their political lapdog. He wants people to support ACT on its own terms.

Remarkably, the party has risen in opinion polls from below 1% to recently as high as 8%. That would give ACT up to ten seats in parliament. Would Seymour also negotiate to bring one or more first-time MPs into cabinet alongside him?

In the past two elections, ACT held on with only one electorate seat, thanks to the National Party deal: Epsom’s National supporters agree to vote for the ACT candidate as their local representative but give their party vote to National.

This arrangement goes back to 2005. It paid a handsome dividend in 2008 when ACT won Epsom and achieved 3.65% in the party vote. This delivered the party a proportional share of five seats, despite being below the 5% party-vote threshold.

With ACT’s support on the right, and two other parties in the centre, John Key formed a National-led government that lasted three terms. Then ACT’s party vote fell below 1% in 2014 and 2017, with only the Epsom seat keeping it in parliament.

In 2020, however, after a term in opposition and no longer overshadowed by National, ACT is flourishing again.

ACT rises at National’s expense

Seymour has held his own, speaking up for freedom of speech and opposing the banning of semi-automatic guns following the mosque shootings in March 2019. He introduced a member’s bill to permit euthanasia that is likely to come into force after a decisive referendum to be held alongside the general election.

However, National leader Judith Collins has bluntly stated she sees ACT’s job as being to win Epsom and to help eliminate the populist New Zealand First Party, which on recent polling is likely to be ousted from parliament on October 17.

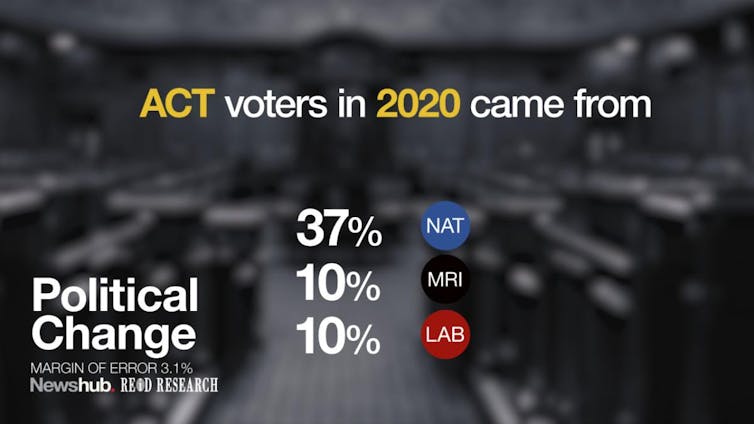

ACT’s rise in the polls does come partly from those conservative erstwhile New Zealand First voters who are disillusioned with Winston Peters for forming a coalition government with Labour.

But Collins must be worried that some centre-right voters have given up on National winning and are exercising their freedom of choice by defecting to ACT — and she wants them back.

What ACT supporters want

The Association of Consumers and Taxpayers was founded in 1993 by former National cabinet minister Derek Quigley and Sir Roger Douglas, formerly minister of finance in David Lange’s Labour government and engineer of the economic deregulation that became known as “Rogernomics”.

The party stands for less government, more private enterprise and freedom of choice. It is, therefore, a child of neoliberalism — indeed, its only legitimate child.

For example, Seymour’s referendum bill to allow assisted dying (euthanasia) was officially named the End of Life Choice Bill, asserting its ideological origins with the word “choice”. He is proposing much more radical cuts to public spending and taxation than his only possible coalition partner, National.

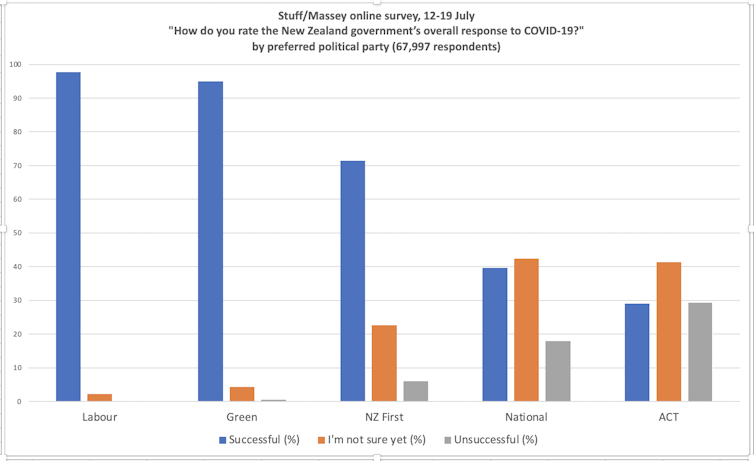

We gained an insight into how ACT supporters think from the online reader-initiated Stuff/Massey opinion poll in July. Compared with the other parties in parliament, ACT supporters stand out as:

- most likely to rate the New Zealand government’s overall response to COVID-19 as “unsuccessful”: 29.5% compared with 9.9% for the whole sample

- most strongly in favour of abolishing the Maori electoral roll: 68.2% compared with 36.6% overall

- more likely to prefer that the government take a “cautious and sceptical” approach on climate change: 72.5% compared with 36.4% overall

- more in favour of the country getting back to “business as usual” rather than reforming the economic system itself during the post-pandemic rebuild: 75% compared with 31% overall.

Populist or purist?

ACT supporters’ values are largely diametrically opposed to those upheld by Green supporters, as might be expected of a libertarian party that stands for individualism and deregulation.

In the past, though, the party has resorted to populist law-and-order and anti-welfare policies. In 2011 it deployed the “one law for all” slogan to attack policies addressing indigenous rights.

As ACT leader since 2014, Seymour has steered the party back towards free-market liberalism. But there is still an element of right-wing populist thinking among ACT’s supporters.

Sizeable minorities of them agree with conspiracy theories about COVID-19 (25%) and hope Donald Trump is re-elected in November (32%) — more than among National supporters who stood at about 20% on both points.

If current polling holds true, Seymour will bring with him into parliament a caucus of freedom-loving individuals, none of whom has any previous representative experience.

Among them is a firearms enthusiast, a former police officer and a farmer. At number seven on the list is a self-employed mother of four who the party claims “is better than ten ivory tower ‘experts’” when it comes to beating poverty.

So far, ACT’s best election result was in 2002 when it gained 7.14% of the party vote and nine seats in the 120-seat House of Representatives. If it repeats that in 2020, Seymour will go from being a lone voice for his party to the leader of a small but inexperienced caucus.

Managing that team of individualistic newbies may well be the first test of his libertarian instincts.

Grant Duncan, Associate Professor, School of People, Environment and Planning, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.