Table of Contents

Dr David Cumin

Spokesperson

Free Speech Union

There is a worrying trend in universities and research institutions attempting to muzzle the very people whose job it is to ask questions. Some subjects are simply now off-limits. Academic freedom is under attack. I’m writing with disturbing news regarding the New Zealand Royal Society, which is on the cusp of giving in to the censors and expelling two scientists for signing a letter defending science. The Royal Society has just launched a disciplinary investigation against a group of academics.

The Royal Society is prosecuting complaints against scientists for defending science!

The Free Speech Union can reveal that two academic fellows are being investigated for being among those to put their name to a letter In Defence of Science which was published earlier this year in The Listener.

For context, the seven professors who co-signed the letter were responding to an NCEA working group that proposed that matauranga Maori should have “parity” with “the other bodies of knowledge credentialed by NCEA (particularly Western / Pakeha epistemologies)” in the school science curriculum. The key argument of the letter was that:

“…Indigenous knowledge is critical for the preservation and perpetuation of culture and local practices and plays key roles in management and policy. However, in the discovery of empirical, universal truths, it falls far short of what we can define as science itself…”.

They further opined:

“Science is universal, not especially Western European. It has origins in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, ancient Greece and later India, with significant contributions in mathematics, astronomy and physics from mediaeval Islam before developing in Europe and later the US, with a strong presence across Asia”.

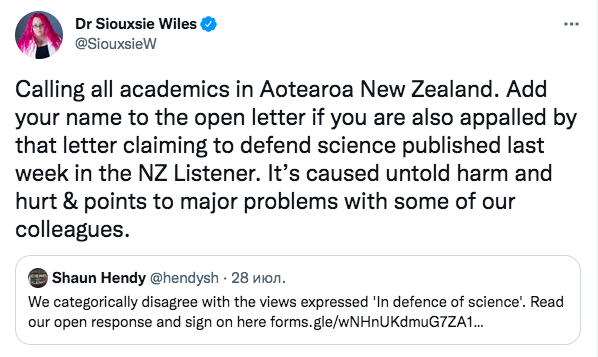

The group who signed the letter faced swift backlash online, led by Shaun Hendy and Siouxsie Wiles:

Dr Barry Hughes of the Tertiary Education Union also wrote a letter to the authors on behalf of the Union. He opened by affirming that the authors were entitled to express their views, but informed them that “[TEU] members found your letter “offensive”, “racist”, and reflective of a patronising, neo-colonial mindset in which your undefined version of “science” is superior to – rather than complementary to – indigenous knowledge”.

Similarly, rather than defend the right of academics to attempt to grapple with difficult questions, Auckland University’s Vice-Chancellor put out a statement stating that asking the question of “whether matauranga Maori can be called science has caused considerable hurt and dismay among our staff, students and alumni”. She too also implied the academics had disrespected matauranga Maori, asserting that “matauranga Maori [is] a distinctive and valuable knowledge system”.

There is nothing, however, in the letter to The Listener that contradicts this. In their letter, the authors argue that matauranga Maori and science are epistemically distinct, and that “indigenous knowledge is critical for the preservation and perpetuation of culture … and plays key roles in management and policy”. So, clearly, the letter actually supports the view that matauranga Maori is valuable.

Notably, none of the criticisms levelled at the authors attempted to grapple with the author’s key contention: that matauranga Maori is simply distinct from science.

While the debate may rage as to whether the author’s assertions are correct, there should be no doubt that the debate must be allowed to take place. That’s why we have offered to help the academics, and crowdfund to defend them with an academic freedom fighting fund.

Whereas the letter to The Listener comprised only a reasoned argument – whether or not it is deemed valid and sound – some critics have resorted to ad hominem attacks on the authors, in particular accusing them – both directly and by implication – of racism. Similarly, proclaiming “hurt and dismay” and pointing to “major problems with some colleagues” does not help the rest of us understand why matauranga Maori should be considered science.

To shut down debate of this kind is to undermine the purpose of the academy: to wrestle with what we know, and try and extend it.

Ironically, the Royal Society was set up for the very purpose of advancing and promoting science, technology, and the humanities in New Zealand. Now it’s trying to expel scientists for defending science.

It is ironic that The Royal Society is trying to purge from the academy the authors of the letter. The investigation of The Listener co-signees sends a chilling message to other academics: state contentious views at your own peril.

If the complaint is upheld, it will only serve to make academics feel less safe to venture honestly-held views on contentious issues in the future. This cannot be allowed to stand. The process of the human pursuit of knowledge depends on free speech, including of those who may hold views contrary to the mainstream. The Royal Society are abandoning its own heritage and the proud traditions of academic freedom which historically has been the defining mechanism allowing scientific knowledge to develop.

When academics can no longer ask questions or make certain arguments, without the fear of personal and professional reprisals, academic freedom is in peril. We must stand with those who are punished and have their reputations denigrated for having the audacity to venture honestly-held views on contentious issues.

The Free Speech Union is starting a fighting fund for Academic Freedom. The academics have been called ‘racist’ and smeared by fellow scientists and are now having to engage lawyers to defend their opinions on science from an institution that should, instead, be encouraging debate and promoting science.

This fight is a fight for the right of anyone to peacefully and reasonably voice their opinion. Times like this make us question the real value we put on our liberties and freedoms. We are not willing to let the Royal Society, or anyone, bully and censor academics doing their job without reminding them that we still have free speech in this country.

The Listener Letter

In defence of science

A recent report from a Government NCEA working group on proposed changes to the Maori school curriculum aims “to ensure parity for matauranga Maori with the other bodies of knowledge credentialed by NCEA (particularly Western/Pakeha epistemologies)”. It includes the following description as part of a new course:

“It promotes discussion and analysis of the ways in which science has been used to support the dominance of Eurocentric views (among which, its use as a rationale for colonisation of Maori and the suppression of Maori knowledge); and the notion that science is a Western European invention and itself evidence of European dominance over Maori and other indigenous peoples.”

This perpetuates disturbing misunderstandings of science emerging at all levels of education and in science funding. These encourage mistrust of science. Science is universal, not especially Western European. It has origins in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, ancient Greece and later India, with significant contributions in mathematics, astronomy and physics from mediaeval Islam, before developing in Europe and later the US, with a strong presence across Asia.

Science itself does not colonise. It has been used to aid colonisation, as have literature and art. However, science also provides immense good, as well as greatly enhanced understanding of the world. Science is helping us battle worldwide crises such as Covid, global warming, carbon pollution, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. Such science is informed by the united efforts of many nations and cultures. We increasingly depend on science, perhaps for our very survival. The future of our world, and our species, cannot afford mistrust in science.

Indigenous knowledge is critical for the preservation and perpetuation of culture and local practices and plays key roles in management and policy. However, in the discovery of empirical, universal truths, it falls far short of what we can define as science itself.

To accept it as the equivalent of science is to patronise and fail indigenous populations; better to ensure that everyone participates in the world’s scientific enterprises. Indigenous knowledge may indeed help advance scientific knowledge in some ways, but it is not science.

Kendall Clements

Professor, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland

Garth Cooper, FRSNZ

Professor, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland

Michael Corabllis, FRSNZ

Emeritus Professor, School of Psychology, University of Auckland

Douglas Elliffe

Professor, School of Psychology, University of Auckland

Robert Nola, FRSNZ

Emeritus Professor, School of Philosophy, University of Auckland

Elizabeth Rata

Professor, Critical Studies in Education, University of Auckland

John Werry

Emeritus Professor, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland