Table of Contents

Peter Murphy

Peter Murphy is Senior Fellow at CFACT. He has researched and advocated for a variety of policy issues, including education reform and fiscal policy, both in the non-profit sector and in government in the administration of former New York Governor George Pataki. He previously wrote and edited The Chalkboard weblog for the NY Charter Schools Association, and has been published in numerous media outlets, including The Hill, New York Post, Washington Times and the Wall Street Journal.

Dubai, UAE.

Week two of the UN climate summit in Dubai is here.

A climate alarmist letter initially with 800 (now 1,400) signatories from business and government, “celebrities,” faith leaders, and others was just released with familiar cliches (“we are at a tipping point”). They call for an “orderly phase-out of fossil fuels” and, by 2030, a tripling of renewable energy. How does all this occur? By the “implementation and ratcheting of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans well before COP30 in 2025.” In other words, the letter is another attempted money grab, particularly from the US, under the guise of more NDCs stemming from the Paris Accord.

“Later is too late,” the letter concludes, which we’ve been reading for 30+ years.

Climate policies come down to coercion. They entail refusing to finance fossil fuel development in poor countries, mandating electric vehicles, blocking gas pipeline construction, and so much else. This invariably raises the cost of fossil fuels to create a “market” for alternative energy. The word “market,” which is often used, is deceitful and Orwellian since little or no market exists for so-called renewable energy, which necessitates mandates and taxpayer subsidies to force them on the public.

The UN does, however, attempt to find climate change solutions to usher in a “just transition” to renewable energy, a commonplace term heard all during COP28. To that end, the UN conducted an “Energy Transition Changemakers” competition among companies to develop carbon mitigation projects.

One of the award recipients was Fatima Al Suwaidi, a director at Masdar-Indonesia, a global renewable energy firm. She presented on the company’s floating solar plant in the Cirata Reservoir in the West Java province of Indonesia, which produces 145 megawatts of power to serve 50,000 homes. The company plans to add to this capacity.

Are floating solar panels remotely scalable or practical? Being from New York State, home of the Catskill and Adirondack forests and mountains with scores of lakes and reservoirs, it is inconceivable to picture a bunch of floating solar panels taking over. Ms Al Suwaidi told me afterward that waterbodies serve places like Indonesia, Japan, and elsewhere since scarce open land is taken up for agriculture; otherwise, the terrain is mountainous. Such projects are a reminder of the clear tension and conflict between

the climate change policies and traditional environmentalism and nature preservation.

Other projects included facilities that replace gas-powered heat with electricity and replace coal with massive battery storage facilities. Unanswered were the extent of government-taxpayer subsidies, reliance on battery ingredients under the control of the Chinese Communist Party dictatorship, and other thorny issues.

The climate awards ceremony occurred at the “Impact” building, a high-tech theater with a seating capacity of 126 that viewed a stage and massive flat-screen equivalent to a stadium monitor. In between the stage and seating is a large ceiling fountain that “rained” water down in a circular fashion before the presentation.

The Expo City campus in Dubai that hosted COP28 is a multi-acre campus the size of a small municipality of numerous buildings, all with state-of-the-art technology. Rest assured: this high-tech capacity could only be powered by fossil fuels, notwithstanding the handful of fake, purple-colored wind turbines wheeled in as a Potemkin display of some faux commitment to renewable energy.

The whole set-up for COP28 far exceeded in scale the make-shift buildings for COP27 in Egypt last year and the two convention centers used in Glasgow, Scotland for COP26 in 2021. It will be hard to equal the capacity of the oil-rich United Arab Emirates to host a convention of 80,000 to 100,000 attendees, but the unofficial word is that next year’s summit will be in Azerbaijan, a former Soviet Republic in southwestern Asia.

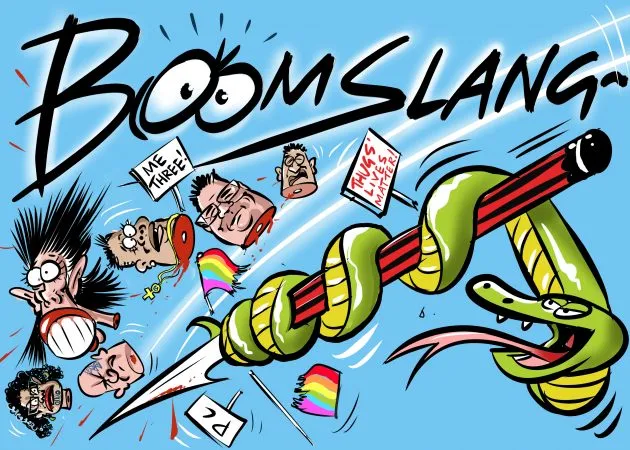

Another observation that will continue to be monitored by CFACT is the increasing visibility of political agendas and causes that are glomming onto the climate issue, including banning meat, reigning in the clothing and fashion industries, opposing Israel and Western military deterrence, demanding workers’ rights, feminism, transgender rights, and more.

Regardless of which side one comes down on these issues, the nexus to climate change is indirect or non-existent. For example, emissions from cows and fertilizer are a worthwhile ancillary byproduct to feed the world’s population with meat products and protein to improve diets; thus, banning beef would be absurd and harmful to millions of people. On the flip side, slavery and child labor in China and the Congo to produce EV batteries, turbines, and solar panels warrants a campaign for workers’ rights, though I noticed no panel discussion including these particulars.

It’s evident that with billions in public and private money flowing to the climate change industry, more political agendas and causes are grifting aboard since, the rationale goes, everything comes back to climate change. This will only lead to increasing and overweening government control of every aspect of individual life and society, including in ostensibly free, democratic nations.