Table of Contents

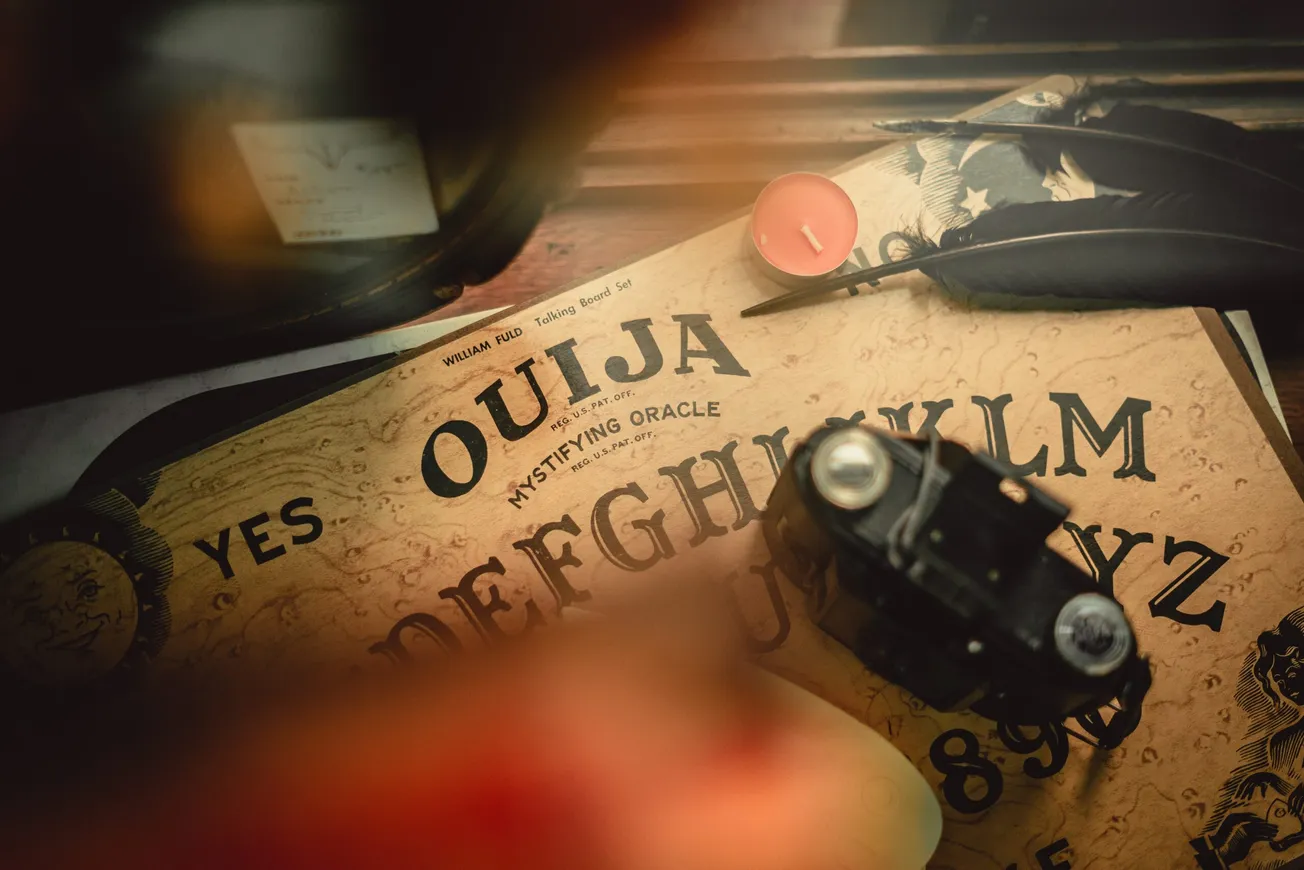

The Ouija board as a channel for demonic forces has become one of the great cliches of horror movies, yet one that refuses to go away. Even the hugely popular Paranormal Activity series featured a Ouija board bursting into flames at the invisible behest of its demonic antagonist. All that is quite a bad rep for what was originally conceived as a fun parlor game.

“Ouija, the Wonderful Talking Board” was first advertised in 1891. “Never-failing amusement and recreation for all the classes!”

But even in the 1890s, the game was indelibly associated with the world of the paranormal, even if not originally in a bad way. Advertising the board as a link “between the known and unknown, the material and immaterial” wasn’t as weird as you might think, at the turn of the last century.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were the heyday of spiritualism. Table-turning, seances, mediums, all the paraphernalia associated with communication between the living and the dead, were big business and a respectable middle-class pursuit. After all, spiritualism was perfectly compatible with bourgeois churchgoing orthodoxy. It was also a movement that offered literally spiritual comfort for a hard age. Victorian sentimentalism was just one outcome of a time when women died in childbirth and many children died young. The devastating toll of WWI also spurred a resurgence of spiritualism in the 1920s.

Quite simply, the idea that they could converse with their many beloved dead was immensely comforting to many people.

The Ouija board was conceived, then, as a way both of making communicating with spirits easier, and, happily, of making a good buck for its creators, the Kennard Novelty Company.

Incidentally, the name is not, as commonly believed, derived from the French Oui and the German Ja (both meaning “yes”). In fact, the name was suggested by the device itself. Helen Peters, the sister-in-law of one of the investors, was supposedly a strong medium. So the investors got together around the board and asked what they should call it: “Ouija”, came the reply – which the board also helpfully informed them meant “good luck”. Supposedly, too, Peters was wearing a locket with a woman’s picture and the name “Ouija”, which some have supposed to be a misreading of author and women’s rights activist Ouida.

So, how did the “good luck” novelty game become so associated with demons and horror? Certainly for decades it was perceived in no such fashion. Norman Rockwell, chronicler of respectable American domestic bliss, showed a couple happily playing with a Ouija board on the May 1920 cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Its popularity grew and grew. In 1944, 50,000 sets were sold in a single New York department store. Two million were sold in America in 1967, outselling Monopoly.

But a persistent undercurrent of titillating terror tales accompanied what, for millions, was harmless fun. In 1921, a Chicago woman claimed that spirits had used a Ouija board to tell her to leave her mother’s dead body in the living room for 15 days, then bury her in the backyard. In 1930, two women in Buffalo claimed that a Ouija board had encouraged them to murder another woman. In 1958, a Connecticut court was asked to rule on a supposed “Ouija board will”.

The true turning point in the perception of the Ouija board came in 1973.

The Exorcist was the movie sensation of ’73. Headlines were filled with lurid stories of people fainting and running screaming out of theatres. The movie, supposedly “based on true events”, prominently featured a Ouija board as something of the gateway drug for the ghostly “Captain Howdy” to possess an angelic 12 year old girl – and manifest as the vomiting, profanity-spitting, crucifix-masturbating demon, Pazuzu. Pop culture perceptions of a harmlessly mysterious parlour game changed overnight.

Now, suddenly the Ouija board was a tool of the devil and a much-used plot device of horror movies. As Dungeons and Dragons was in the 80s, the Ouija board was sudenly denounced by religious groups. That denunciation has never really let up. Even in 2001, it was burned on bonfires along with Harry Potter and, of all things, Disney’s Snow White. Even the Catholic church’s official website warns that the board is “far from harmless”.

Even the New Agey, spiritualist types suddenly became afraid of what was once their tool. A researcher specialising in the history of the board comments that he is asked not to bring his antique boards to paranormal conventions, because they scare people.

Such is the power of and protean nature of pop culture. What was once a source of spiritual comfort became a bit of Halloween fun, and now, a veritable gateway to Hell.

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with your friends.