Table of Contents

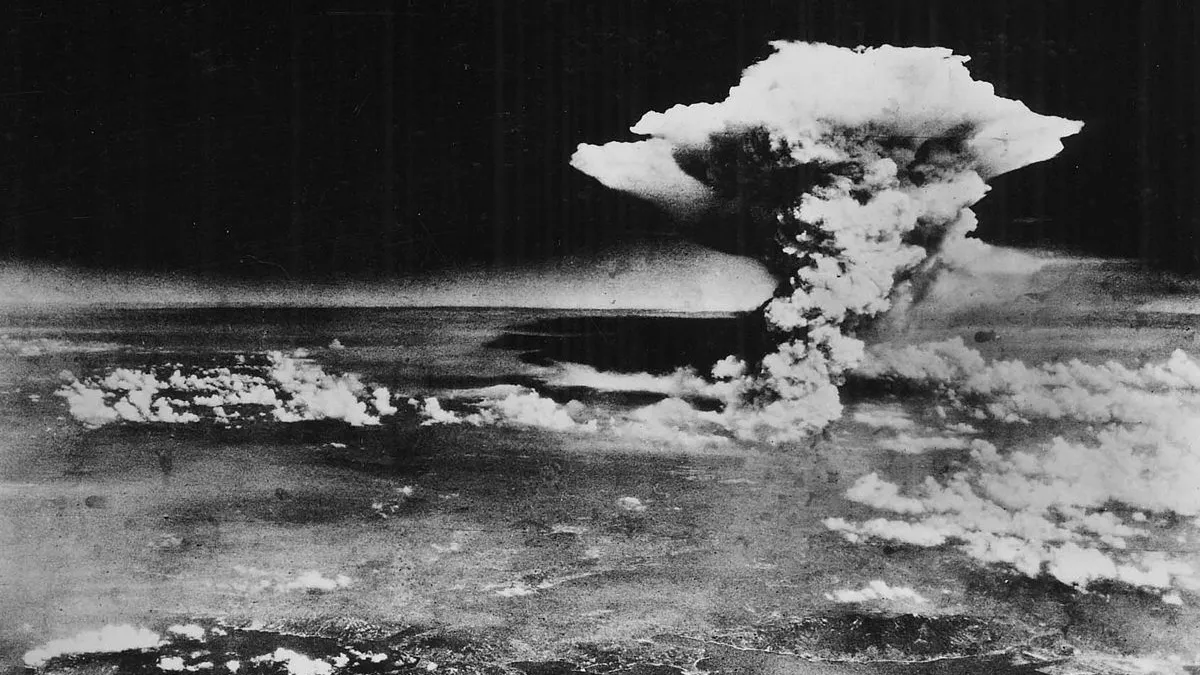

The recent 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki prompted the usual argy-bargy over whether the bombs were morally justified (they were). But what would no doubt horrify pearl-clutching Guardian readers is the little-known fact that the Allies were fully prepared to drop more bombs if they had to.

At least one more, possibly four.

Most Americans believe that dropping two atomic bombs on Japan was always the plan. But the historical evidence shows otherwise. Not a single document from before Japan’s surrender indicates that only two bombs were to be used. It wasn’t until after the war ended that new meaning was given to the bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A surge of memoirs produced by those involved in the Manhattan Project asserted it was common knowledge that two atomic bombs would be enough.

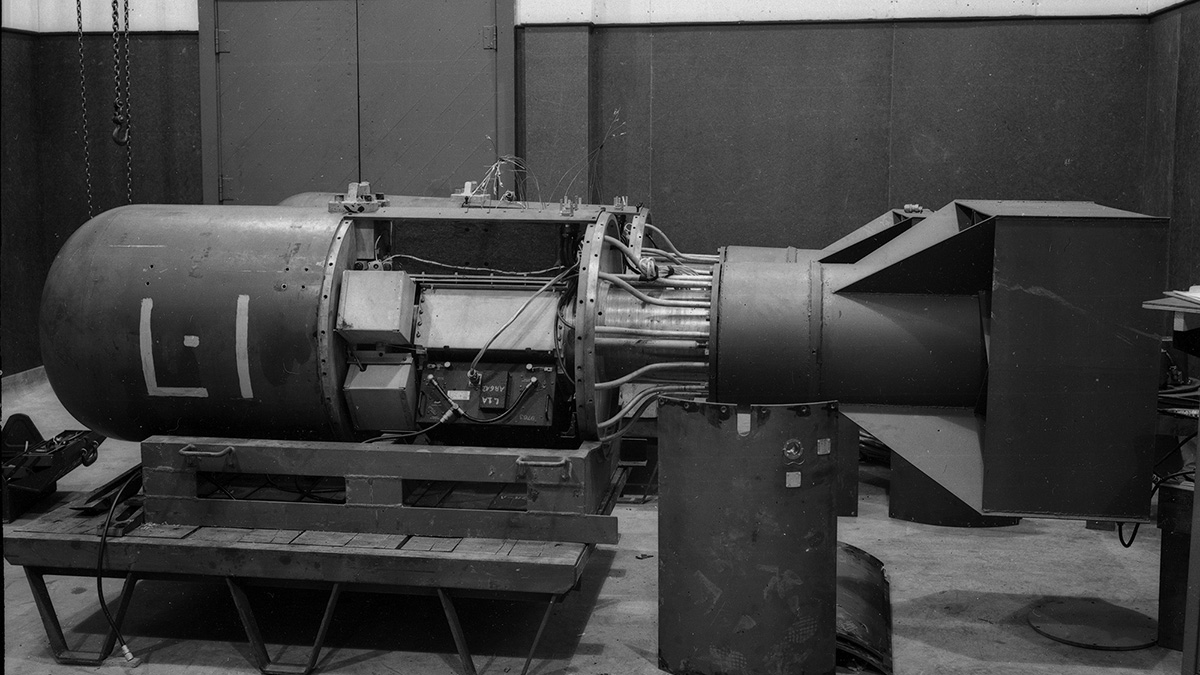

But, before the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, no one thought two bombs would end the war. Most certainly, not the two men in charge of the Manhattan Project. Three days after the Trinity Test, General Groves wrote to Oppenheimer that it would be necessary to drop Little Boy and Fat Man and possibly two more Fat Man bombs.

American military planners had good reason to think so. The same sound rationale that led to the use of the bomb in the first place dictated that such a contingency at least be planned for. Japan had never before surrendered in its two-and-a-half thousand year history. No military unit had surrendered through the entire war. Commanders had good reason to believe that, even should the government surrender, soldiers in the field would not.

Indeed, even in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that’s exactly what happened. The Kyujo Incident, on the night of 14-15 August, was an attempted military coup d’état which aimed to murder the prime minister and place the Emperor under house arrest, in order to prevent the surrender order going out.

The pilot of the plane that dropped Little Boy, Colonel Paul Tibbets, told varied accounts. According to his earliest recollection, it would take five atomic bombs to force surrender. He had fifteen bombers and trained crews ready to go in case they needed to drop more atomic bombs during the war.

On August 13, 1945—four days after the bombing of Nagasaki—two military officials had a phone conversation about how many more bombs to detonate over Japan and when. According to the declassified conversation, there was a third bomb set to be dropped on August 19th. This “Third Shot” would have been a second Fat Man bomb, like the one dropped on Nagasaki. These officials also outlined a plan for the U.S. to drop as many as seven more bombs by the end of October.

The location for the third bombing remains unknown. At least one official advocated for Tokyo to be the site of the next atomic strike. He argued that attacking Tokyo would cause immense psychological damage for any government officials that remained in the city. To him, this was far more important than the destructive force of the bomb itself.

The Japanese leadership’s ability to deny cold facts was also another contingency the Americans had to reckon with. Not to mention that this was a weapon completely beyond anyone’s experience (not even the scientists of the Manhattan Project had been able to agree on its destructive potential – prior to the Trinity test explosion, many doubted that it would yield much at all).

Even after Hiroshima, Japanese leaders clung to denial. A team of Japanese atomic physicists surveyed Hiroshima the day after the bombing and reported back to Tokyo that, just as American radio broadcasts were saying, the city had been destroyed by a nuclear weapon. The Chief of the Naval General Staff, Admiral Toyoda declared that the Americans could have no more than one or two bombs remaining. The Japanese cabinet decided to endure the remaining attacks: “there would be more destruction but the war would go on”. American codebreakers intercepted the communiques.

The Americans obviously concluded that it would at least take a bomb dropped right on them to convince Japan’s leaders to surrender. Meanwhile, Nagasaki was bombed.

While the military continued to prepare for a third atomic strike on Japan, President Truman asserted control. When he learned that a third bomb would be ready in about a week, he ordered that there be no more atomic bombs dropped without his direct approval. When Truman was later asked why he wanted to halt nuclear strikes against Japan, he said that the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people and killing “all those kids” was too horrible.

Truman was not alone in his moral qualms. Even tough-minded military leaders like Air Force General Curtis LeMay thought there was “no point in slaughtering civilians for the sake of slaughter”.

The problem they had to reckon with, though, was that in Japan the distinction between soldiers and civilians was not clear-cut. All Japanese men aged 15 to 60, and women from 17 to 40, were drafted into a militia armed with bamboo stakes and clapped-out old guns. At the Battle of Mutachiang, firemen had acted as suicide bombers.

Even after Japan surrendered on August 15th, there were fears of a militarist coup in Japan that would restart the war. Preparations for the third atomic strike continued until September 2nd—the day the American Occupation of Japan began[…]

Japan’s surrender erased the Third Shot from popular memory, helped along by a revised narrative from official sources. The idea that it was always meant to be two bombs settled into the stories American’s told about the war. And just like that, the Third Shot was forgotten.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.