Table of Contents

Lindsay Mitchell

Lindsay Mitchell has been researching and commenting on welfare since 2001. Many of her articles have been published in mainstream media and she has appeared on radio, tv and before select committees discussing issues relating to welfare. Lindsay is also an artist who works under commission and exhibits at Wellington, New Zealand, galleries.

The public service’s dogged determination to impose Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations across the sector results in the absurd and incongruous.

According to Oranga Tamariki, formerly Child, Youth and Family:

Oranga Tamariki is currently introducing a new practice approach (completion 2024) that is framed by Te Tiriti o Waitangi, based on a mana enhancing paradigm for practice, and draws on Te Ao Maori Principles of oranga and transpires into a practice that is relational, inclusive, and restorative which is good for all tamariki, children, whanau, and families.[i]

It sounds rather like the ‘Maori way or the highway.’ In 2021 Te Pati Maori, supported by Children’s Minister Kelvin Davis, insisted that OT adopt a ‘by Maori, for Maori’ approach.

Children in OT care are now put into “four high-level categories”: Maori, Pacific, Maori/Pacific, and lastly, as an after-thought almost, NZ European and other.

But the definitions have become even more indistinct.

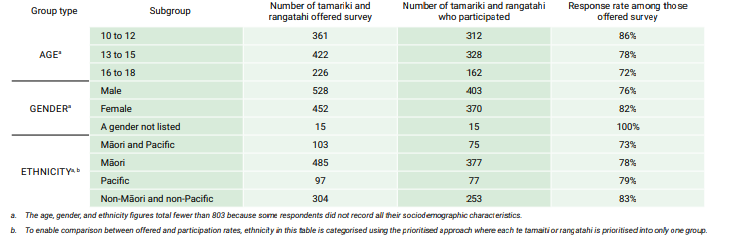

Just published, a survey of children and young people in state care contains the following table which illustrates my point:

Children in the care of OT are now categorised as either Maori, Pacific, Maori and Pacific or non-etc.

Cultural identity is ‘paramount’ apparently … but if you are Asian or Indian or NZ European … yeah … nah. You are just non-Maori or non-Pacific. The details of your lineage are of no account. In truth the only cultural identity of interest is Polynesian and OT struggles to disguise this.

How does the “bi-cultural practice” advocated in OT’s ‘Maori Cultural Framework’ serve, for example, a refugee child? When I asked OT which two cultures the framework catered to, the answer was inconclusive:

Under the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, the Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki must ensure, wherever possible, that all policies adopted by the department, and all services provided by the department, recognise the social, economic, and cultural values of all cultural and ethnic groups; and have particular regard for the values, culture, and beliefs of Maori.

I can only interpret that as Maori and other. Whatever happened to multiculturalism?

Oddly though, in this ‘by Maori, for Maori’ organisation, in April 2023 only 28 per cent of staff were Maori. Nearly three quarters weren’t.

And here’s another irony. Of those who answered all the questions in the survey referred to, “99% answered in English only, none answered in Maori only, and less than 1% answered in both English and Maori.”

Staff are predominantly NZ European, and the language used by staff and their clients is predominantly English.

Oranga Tamariki’s crucial role is to ensure the safety and security of children. All and any at-risk children. Yet the survey itself showed “little overall improvement in tamariki and rangatahi experiences.”

Their fixation with culture is a crock.