Table of Contents

Kath Murray

Research Fellow in Criminology

The decision to place double rapist Isla Bryson in the segregation unit at Scotland’s Cornton Vale women’s prison, ahead of sentencing, has sparked a political crisis that looks unlikely to abate soon.

Following a backlash, Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon quickly announced that Bryson would not stay at Cornton Vale. That same day, Bryson was moved to a male wing at His Majesty’s Prison Edinburgh. The Scottish parliament’s justice committee has confirmed that it will scrutinise these events.

How did we get here?

The Scottish Prison Service issued its current gender identity and gender reassignment policy in March 2014. This allows prisoners to be accommodated based on self-declared gender identity, subject to a case-by-case assessment.

Work on the policy began in 2007 in close collaboration with Scottish government-funded group Scottish Trans Alliance, whose logo has equal weighting to that of the SPS on the policy document.

Responsibility for decision-making lay with the Scottish Prison Service, whose job was to balance the needs of different groups. That it failed to do so, in this case, is obvious.

As the service’s own equality impact assessment of the policy, dated 2014, shows, officials did not consult with groups representing women’s interests, nor consider relevant documentary evidence on women.

It concluded that women would not be affected by the new policy.

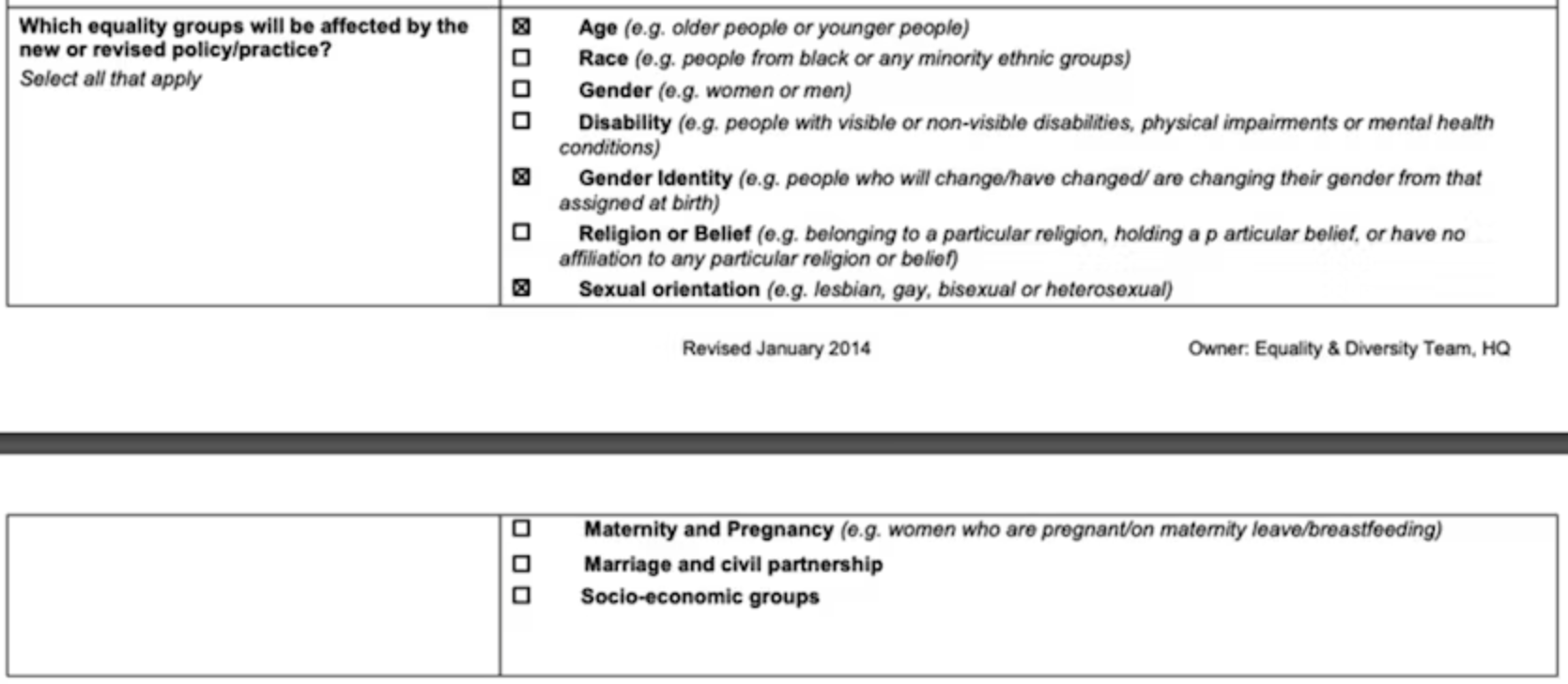

The assessment identified three protected characteristics that could be affected by the policy: age, “gender identity” and sexual orientation. The box for “gender” was however, left blank. It should also be noted that the correct protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010 are gender reassignment (not gender identity) and sex (not gender).

The needs of female offenders

The later stages of development on the 2014 gender identity and gender reassignment policy coincided with the publication of the Commission on Women Offenders report (The Angiolini report) in 2012. The report captured the complex needs and troubled histories of female offenders, documenting high rates of mental health problems.

It noted specifically that around 80% of those housed at Cornton Vale experience mental health problems. It showed that women prisoners have “higher lifetime incidences of trauma, including severe and repeated physical and sexual victimisation than either male prisoners or women in the general population”.

Over the next decade, the Angiolini report shaped Scottish prison policy. In an address made in May 2015, the first minister acknowledged “recent developments and improvements in the care of women in custody”, citing a staff programme that recognised “many of the women will have experienced trauma and mental ill-health”.

In 2019, the Scottish Prison Service published its new model of custody for women, detailing how a trauma-informed approach would underpin operational practice. It said, “Women who have suffered some type of physical or emotional trauma are often hyper-aware of possible danger,” and “survivors of trauma may find it difficult to trust others.”

The Scottish Prison Service’s strategy for women in custody 2021-25 described the Angiolini report as a “significant catalyst for change”, stating all aspects of care should “take account of their likely experience of trauma and adversities”.

At the same time, officials continued to accommodate transgender prisoners in the female estate. While the Scottish Prison Service has only recently begun to publish statistics on the placement of transgender prisoners, media reports show that offenders placed in the female estate include those convicted of: murder (multiple examples); murder and torture; murder and assaulting a female prison officer; multiple violent offences; voyeurism and sexual assault; and threatening and abusive behaviour.

None of these cases appeared to trouble Scottish ministers. It would take a full-blown political crisis for them to pay attention.

That the Bryson case gained traction is a matter of timing. The story unfolded against the backdrop of the recently passed Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Act, which, controversially, put the principle of self-identification on a statutory basis.

The UK government subsequently issued an order preventing the act from proceeding to royal assent, stating that the act would adversely affect UK-wide equalities legislation. In this context, the Bryson case, which arose directly from a policy based on self-identification, became part of a larger political and constitutional story.

Damage limitation

In a bid to stem the tide of criticism being levelled at its handling of the Bryson case, the Scottish government has announced interim rules on housing transgender prisoners. Meanwhile, a longstanding policy review of the management of trans prisoners is nearing completion.

The interim measures are limited, however. They only state that those transgender offenders with convictions of violence against women (including sexual offences) will not be placed in the female estate.

Notwithstanding that most violent or sexual offending goes unreported and few cases are prosecuted in court, the measures appear trauma-blind. Minimal reassurance is provided in respect of women’s psychological safety, dignity and privacy, or to those re-traumatised by male bodies or voices.

The Bryson case reveals a long-standing tension in Scottish prison policy between gender self-identification principles and trauma-informed care.

For the best part of a decade, this contradiction has played out in plain sight, with minimal scrutiny, to the detriment of female offenders. That it has taken the case of a double rapist to bring it to the fore raises serious questions about political priorities as well as the susceptibility of public authorities to lobbying.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.