Table of Contents

It’s one of the classic scenes of movie comedy: Tha’s nae ordinary rabbit! When Sorcerer Tim warns King Arthur and his questing knights that the way to the Grail lies through a cave “guarded by a creature so foul, so cruel that no man yet has fought with it and lived”, the last thing they expect to see is a fluffy white rabbit.

Even when Tim warns, “That’s the most foul, cruel, and bad-tempered rodent you ever set eyes on! Look, that rabbit’s got a vicious streak a mile wide! It’s a killer!”, even cowardly Sir Robin scoffs. “What’s he do, nibble your bum?”

And then the rabbit proceeds to rip the throats out of three of the knights.

The joke, of course, is that a harmless and gentle creature such as the fluffy and timid rabbit could ever be a vicious killer. But it’s not such a modern joke, after all. It’s no coincidence, perhaps, that one of the Python crew, Terry Jones, studied mediaeval history at Oxford. Where, presumably, he would have been well aware of the mediaeval tradition known as “drollery”.

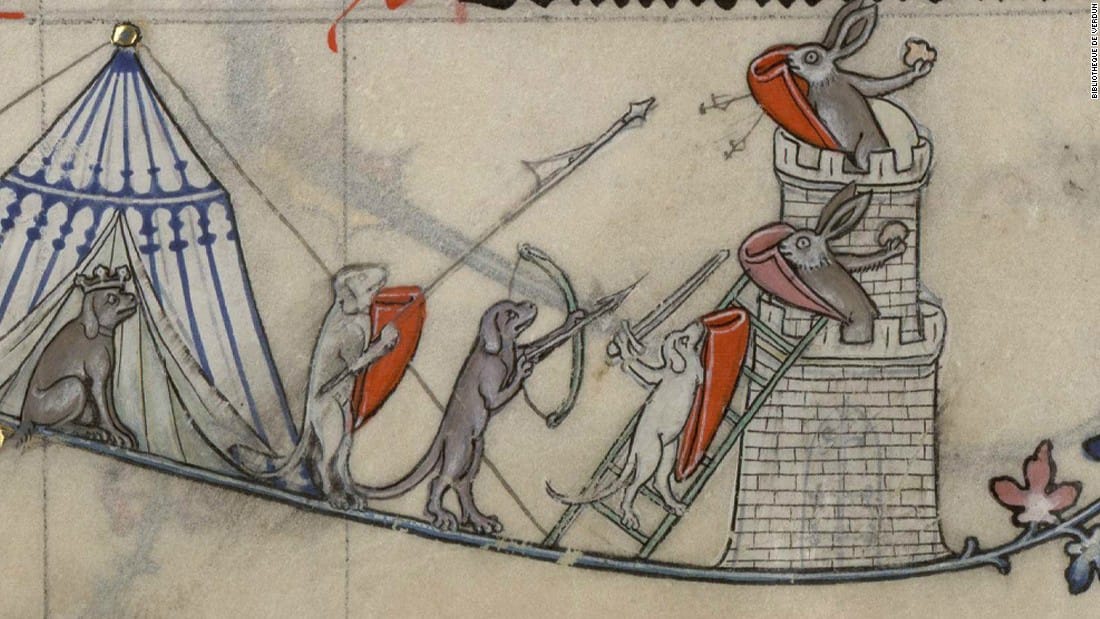

Drollery was the practice of including humorous illustrations in the marginalia – the rich illustrations – in the margins of illuminated manuscripts. Marginalia are replete with weird imagery of monsters and people. Other, even in religious texts, are simply mediaeval funny pictures. Some make fun of monks, nuns and bishops, or are humorous commentaries on mediaeval life. Hunting scenes are common and, in some of those, the mediaeval illustrators apparently decided to have some fun with role-reversal.

Enter, the killer bunnies.

Author/historian Jon Kaneko-James explains:

“The usual imagery of the rabbit in Medieval art is that of purity and helplessness – that’s why some Medieval portrayals of Christ have marginal art portraying a veritable petting zoo of innocent, nonviolent, little white and brown bunnies going about their business in a field.”

Like comedians the world over, throughout history, mediaeval jokesters enjoyed humour based on up-ending social mores. Thus was created the genre of drollery known as “the rabbit’s revenge”. As George Orwell noted, “If you had to define humour in a single phrase, you might define it as dignity sitting on a tin-tack. Whatever destroys dignity, and brings down the mighty from their seats, preferably with a bump, is funny. And the bigger they fall, the bigger the joke.”

Killer bunnies were great bringers-down of the high-and-mighty.

“[‘Rabbit’s revenge’ was] often used to show the cowardice or stupidity of the person illustrated. We see this in the Middle English nickname Stickhare, a name for cowards” – and in all the drawings of “tough hunters cowering in the face of rabbits with big sticks.”

Then, of course, we have the bunnies making their attacks while mounted on snails, snail combats being “another popular staple of Drolleries, with groups of peasants seen fighting snails with sticks, or saddling them and attempting to ride them.”

Open Culture

Because these animals were so low on the totem pole of fear, it was quite amusing to the medieval illustrator to draw them enacting a revenge – silly animals on the opposite side of the slaughtering. This was also a way for the artist to show the stupidity of the human who was the object of the rabbits’ anger, one who was foolish enough to be bludgeoned by bunny.

Colossal

Just like the world’s oldest recorded joke (the Sumerian knee-slapper, Something which has never occurred since time immemorial: a young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap), you often presumably had to be there. Drawing a barber with a wooden leg, “for reasons that escape me, was the height of medieval comedy”, says Kaneko-James.

Not the killer bunnies, though: they’re still hilarious. That much is proved not just by Monty Python’s sketch, but by the fact that drollery images of violent rabbits are enjoying a new round of popularity today as social media memes.

But demonic figures blowing trumpets up each other’s bums? I guess you really did have to be there.