Table of Contents

The Krakatoa explosion of 1883 is generally held to be the loudest sound recorded on Earth: even louder than the doof of a boy racer’s subwoofers. But neither of those sounds has anything on the ear-splitting screech of Boomers asked to spend a fraction more of their stupendously outsized wealth to pay for their own aged care.

The Boomers are the richest generation in history. Most of that wealth passively earned via the housing market. Boy, do they love to show it, too: from the gargantuan SUVs to endless luxury cruises.

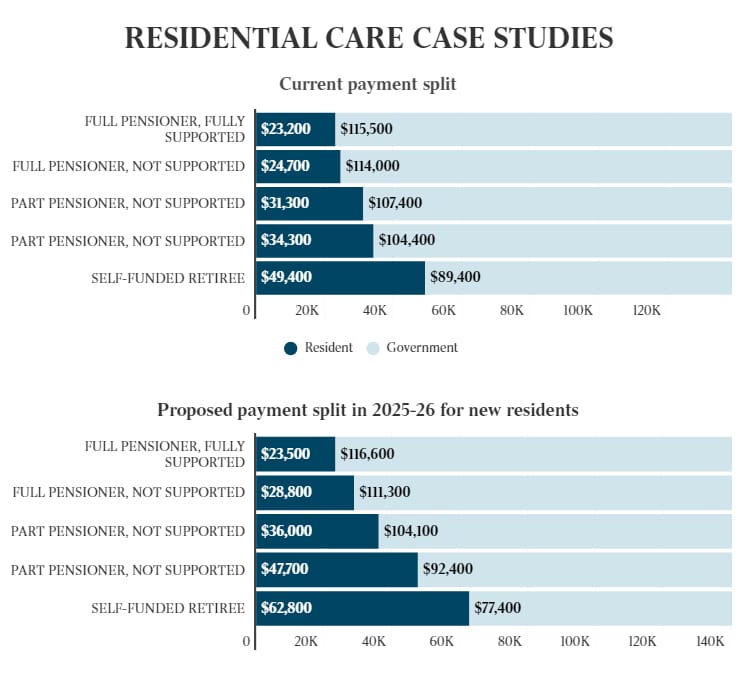

But having capitalised the profits of the housing crisis, when it comes to footing the bill for their senescent health care, though, suddenly the Boomers are all about socialising the costs. Not a single segment of the over-65s pays for the majority of their aged care. Even self-funded retirees receive more from the public purse than they pay.

With Australia relying more on income tax for revenue than most countries, funding the luxurious retirement of idle rich Boomers who pay little or no income tax is clearly not a sustainable model. In fact, they pay even less than their parents did in retirement: ‘the proportion of older Australians who pay personal income tax has generally declined over time, largely due to the introduction of age-related tax offsets and changes to the taxation of superannuation income,’ Treasury’s Intergenerational Report (IGR) notes.

Successive Australian governments have been painfully aware of the growing imbalance of struggling young lifters, compared to wealthy elderly leaners, for decades. But the power of the Grey Vote has meant that nothing meaningful has been done about it. Apart from lifting the retirement age for the luckless generations who have to clean up after the profligate Boomers.

For once, though, and in a rare win for both the Albanese government and the Australian taxpayer, the bipartisan Aged Care Taskforce has announced that Boomers will be forced to loosen their wizened claws on their hoarded gold, even if just a little.

From July next year, residential aged care residents with “sufficient means” would pay more for non-clinical services, such as showering, haircuts and lifestyle activities, with the lifetime contribution cap lifting from around $76,000 to $130,000. It’s not a massive impost given, as the taskforce found, “the increasing wealth of many older people and the declining working age (that is tax paying) population”.

According to case studies circulated by the government, a self-refunded retiree with an income of $70,000 and $500,000 in assets, excluding the family home, would see their contributions rise from $49,400 to $62,800 a year. A part-pensioner with $500,000 in assets would see their fees rise from $34,300 a year to $47,700. A full pensioner who owns their own home and has other assets worth $150,000 would pay $28,800, or an extra $3000 a year.

There was a time when the Boomers were big on ‘mutual obligation’: a time roughly between when the then-comfortably middle-aged Boomers supported John Howard and Peter Costello’s imposition of mutual obligation on the mostly young unemployed, and when they realised that it might apply to them in retirement.

Due credit to Labor, it’s put mutual obligation at the heart of its Aged Care reforms.

[Aged Care Minister Anika Wells] explained the key principles of the package. First, mutual obligation: Australians will get the support they need and make a reasonable contribution based on their means. Second, a “no worse off” principle, meaning those already in care won’t pay more.

Third, taxpayers will pay all clinical care costs, but individuals would contribute to living and personal care costs. Fourth, the government will continue to pay the majority of aged care costs. “Without structural change, we will not be able to sustain the level of care older Australians deserve,” Wells said. “It is that simple.”

There’s a sweetener, of course – and it’s one that makes sense.

But the big move was the reorientation of aged care to support people at home, the clear preference for ageing boomers, the first of whom will turn 80 when the new era begins. Over the next decade, 300,000 more people will receive aged care services in their home; average wait times from assessment to support will fall.

At present, the wait for an Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) assessment was at least six weeks. The wait after that, for a package to be approved can be, depending on its urgency, anywhere between a month (level one care) to up to a year (levels three and four). So bringing the wait down is good and allowing people to stay in their own homes, even better. Especially when it comes to the end of life.

The new approach includes giving terminally ill people up to $25,000 to receive palliative care support to spend the final months of their lives at home, as well as $15,000 for people to modify their homes so they are safe to live in […]

Many wanted the politicians to go further. While the government has ruled out increasing the means-test threshold for the family home, CEDA’s Cilento says it “should consider lifting the threshold to around $500,000, reflecting the significant rise in home values over the past decade”.

Meanwhile, residential aged care needs up to a $56 billion dollar upgrade, and poorly paid aged-care workers will need substantial pay rises to stem the flood of workers from the sector.

All that costs a lot of money: who’s going to pay?