Table of Contents

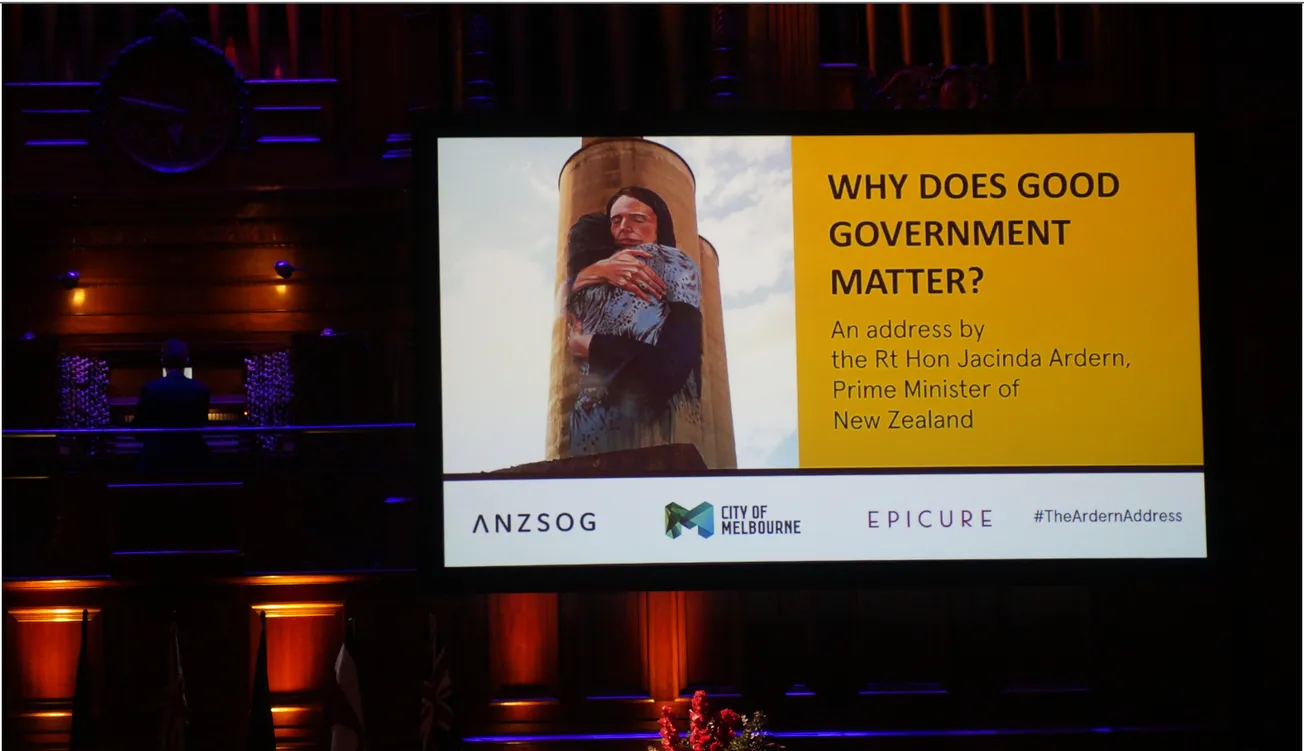

Why does good government matter?

Part Two:

Inequalities past and present

We can start with the state of many developed economies. While they continue to grow in overall economic terms (if not as quickly as they once did), they have too often failed to share the benefits of that growth.

In many countries, while the very wealthiest have grown consistently wealthier, the rest have seen little or no real rise in their incomes or their living standards – over decades.

Inequalities that deepened with the great deregulating reforms of the 1980s and 90s have become a permanent feature of these economies – not a brief moment of pain.

That is certainly the case in New Zealand.

As a small country, we are often at the forefront of global trends, because we can move faster and sometimes further than our larger counterparts. That was evident in the way we embraced – and sometimes pioneered – the free-market reforms of the 1980s and 90s.

Starting in 1984, through to the 1990s, we removed regulations that were said to hamper business, slashed subsidies, transformed the tax system, dramatically cut public spending and massively reduced welfare benefits paid to the sick, those caring for children and the unemployed.

Now we can argue whether those regulatory reforms were necessary, but regardless the numbers speak for themselves.

Within 20 years, my country lost its status as one of the most equal in the OECD. While incomes at the top doubled and GDP grew steadily, incomes at the bottom stagnated and child poverty more than doubled.

I was a child back then, but I remember clearly how society changed. I remember nothing of the Rogernomics of course– I was 5 and I was not the Doogie Howser of politics. But I do remember the human face. Especially the kids who just didn’t have the basics.

This experience is not New Zealand’s alone. It happened in many countries, often with deeper inequalities and more persistently stagnant real wages.

And the change hasn’t always been reversed yet. In fact, more recent trends have added new dimensions to the problem.

The financial crisis of a decade ago did not turn into another Great Depression, thankfully – but it has led to ongoing upheaval in the global political economy.

High debt and prolonged low interest rates have inflated asset values, widening inequalities in new ways. Most obviously for countries like New Zealand and Australia, booming housing markets have put home ownership out of reach of a growing number of younger people, especially when coupled with the debt many accumulate trying to further their education.

That same generation that is facing the prospect of new challenges – climate change and digital transformation putting people out of work now and into the future.

And just to add fuel to that already grim picture, new forms of media and communication are changing how we understand what is happening in our societies – and how we connect with each other. This change has opened up the world, in one sense – but it has also had the opposite effect of making us more distant, at times more entrenched. Stunningly, our most connected generation in New Zealand, has also been found to be our loneliest.

In the face of this fragmentation and disillusion, what does good government look like, not for us but for the very people who are turning away from us?

Two paths

I’ve already mentioned one potential answer to this question.

In recent years, we have seen politicians and governments of all stripes respond to the stresses and challenges I have outlined by turning inwards.

Domestically, some have chosen to reject the independent and expert public service and the possibility of a mutually respectful and diverse nation.

Abroad, they reject the international institutions that they paint as responsible for both economic and cultural problems when they aren’t necessarily at fault.

So this is one answer that is available to people – and that some are signing up for. After all, fear and blame is an easy political out.

As I say, I understand how we got to this point. But I reject this answer.

Because there is another response. Instead of turning inwards, we can improve the institutions that have helped hold together this long period of global peace that we live in.

Instead of austerity measures that only stretch the rich-poor divide, we can offer meaningful support – and more than just financially – to those at the bottom.

Instead of tearing down what works about our societies, we can build the system back up. We can acknowledge the areas where public policy hasn’t met the challenges of economic change, and do better.

One of the ways we can do this is by widening our idea of what prosperity means. Because if a country has been growing economically for 30 years, yet large numbers of its citizens haven’t felt the benefit, is it really moving forward?

If a country has a relatively high rate of GDP growth, but it is neglecting the things that we should all hold dear – like the health of our children, a warm, dry home for all, mental health services or rivers and lakes that we can swim in – then can it be said to be improving?