Table of Contents

Bryce Edwards

I am Political Analyst in Residence at Victoria University of Wellington, where I run the Democracy Project and am a full-time researcher in the School of Government.

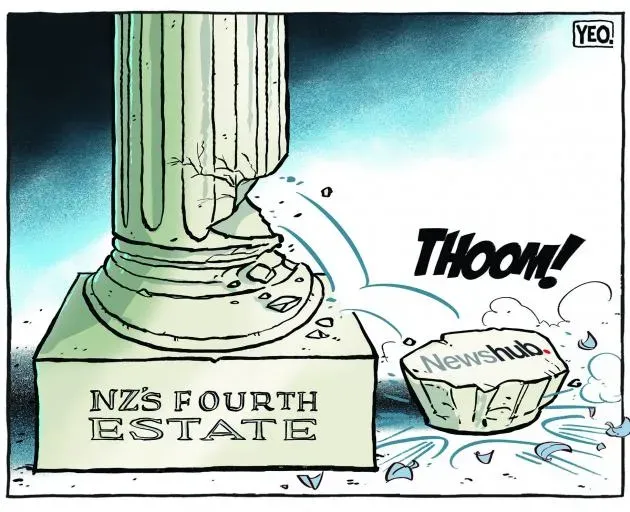

Democracy is the loser whenever a major media company disappears. We’ve seen a total consensus about this in the last two days – politicians, academics, and journalists have commented on the demise of Newshub, pointing out that a reduction in journalists reporting on and investigating current affairs and politics does not serve the democratic goal of an informed public.

Newshub’s demise is a win for vested interests and the “influence industry”

While democracy is the loser, there’s also a likely big winner from the demise of Newshub – the powerful in society, who can operate with less accountability and scrutiny. Individual politicians, decision-makers, officials, businesses – and vested interests in general – are all advantaged by any decline in the ability of journalists to “speak truth to power”. Newshub’s death will mean there will be fewer voices questioning authority and the status quo.

This ongoing battle between the powerful and the public media has been becoming more and more one-sided over recent years. As the institution of the media declines in power, the power of public relations and closely connected industries like lobbying grows much stronger.

This is reflected in the numbers involved in such jobs. At the last count, in 2019, roughly 1,600 journalists were working in print and broadcasting. And according to a report commissioned by the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, between 2000 and 2018 the number of journalists fell by 52 percent. But the numbers in the PR industry are booming – in 2019 there were about 8,000 people. Other calculations have put the ratio of PR to journalists at 10:1.

Last year, Herald journalist Damien Venuto reported on the balance between the two industries, saying that while “the number of journalists covering news in this country has more than halved… At the same time, we’ve seen an explosion in the PR industry” – see: The public relations power list: The most influential PR people in New Zealand (paywalled).

Venuto listed the various journalists and broadcasters that had switched sides to PR, stressing the “huge increase in the PR ranks”. Notably, Venuto announced a few months later that he was leaving journalism for a PR job.

Many of the PR professionals work directly for politicians, government departments, or local government authorities. “Communications” is a booming sector of politics and government. According to the Public Relations Institute of New Zealand, the public sector is the main employer of comms staff. And government agencies have been on a big recruitment exercise in recent years, often poaching journalists from the media.

And the numbers in the “influence industry” are increasing. It’s been reported that during the six years of the last government, the number of comms staff employed by government agencies went up by 57 percent, with a total of 532 comms employers in April last year. Some government departments have huge numbers. And outside of the core public service, there are even more – for example, Te Whatu Ora was reported to have about 200 comms staff.

There are over 300 comms staff working in local government. Andrea Vance reported this week that the beleaguered Wellington City Council now spends $5.3m on comms each year – mostly paying its 54 PR staff. Last year it was revealed that Christchurch’s two local authorities have about 100 comms staff.

Many of these PR staff are employed to deal with journalists [and] the public and generally be gatekeepers of information. As veteran journalist Karl du Fresne explained last year, this is about control of information: “In the comms war, meanwhile, the balance of power has long since shifted from those trying to get information to those controlling it. They are unseen influencers whose role is invisible to everyone other than the people they work with. This has serious implications for democracy and transparency” – see: The incredible disapppearing journalists.

Du Fresne explains that the expansion of comms staff – especially in government agencies – hasn’t improved public access to information, but quite the opposite: “many journalists will tell you that generally speaking, the ease of obtaining important information from government organisations tends to diminish as more comms people are employed.” And he tells the story of how the Police boasts that it employs more trained journalists than most media newsrooms.

Job opportunities in PR, consultancies, and lobbying will doubtlessly mop up many of the 350 jobs threatened by Newshub’s demise. And some of the top journalists will go over the “dark side”. And the pay is much better – with journalists generally reporting the receipt of raises of between 50 and 100 percent when they go to PR or lobbying.

Note, for example, that earlier this year, TVNZ’s then political editor Jessica Mutch McKay went to work as a lobbyist for a bank. The Herald’s media insider Shayne Currie writes today: “As we saw with Jessica Mutch McKay’s recent move to the ANZ, there is demand in the PR and corporate world for well-connected journalists and broadcasters” – see: TVNZ’s ‘tough’ result – Shortland Street, shows in costs spotlight; Newshub talent eye new gigs; Broadcasting Minister under fire (paywalled).

Currie suggests that many of the departing Newshub talent will be swept up quickly: “Expect the likes of Ryan Bridge, Paddy Gower, Rebecca Wright, Michael Morrah and others to be among prime big-name targets, on a range of fronts. The network’s two biggest stars, Samantha Hayes and Mike McRoberts, carry huge mana.” While those individuals can hardly be blamed for adding even more heft to the industrial-influential-complex in New Zealand, the shift of such talented broadcasters and journalists into lobbying and PR might end up being the biggest tragedy in Newshub’s demise. We are increasingly living in a Public Relations Democracy.

What happens to Newshub now?

What happens to Newshub now? While its corporate owners seem determined to close the newsroom down, there are other options floating around. Some Newshub employees want to put together an alternative proposal to save the operations. Investigative reporter Michael Morrah says that he and other senior Newshub journalists are meeting next week to put together a proposal to keep their newsroom going – see Tom Dillane’s Newshub senior journalist Michael Morrah says proposal will be made to save axed news operation.

Former Head of News at Newshub Mark Jennings has advised that the pitch should involve massive cuts to the costs, getting rid of foreign correspondents, only having one news reader, and cutting the 6pm bulletin to only 30 minutes.

Another option could see Sky TV taking over some of Newshub’s assets, employees, and products. Sky already contracts Newshub to produce its 5.30pm news bulletin. And the Spinoff’s Duncan Greive wrote yesterday that Sky “just announced some strong advertising figures, and is putting a bunch of sport into its rebranded Sky Open channel. Newshub won’t be making its 5.30pm news product any more – but is there an opportunity for it to make a play to use a news product to take over Three’s position in our minds and living rooms?” – see: Five key questions about the massive layoffs at Three and Newshub, answered.

So, there’s every possibility that some more cheaply produced news and current affairs programming could yet turn up on Sky TV, featuring the likes of Ryan Bridge.

Another option that has been discussed before is for Newshub to work collaboratively with other broadcasters to establish a joint newsroom to supply stories to all the networks. This would have some appeal to other outlets who are struggling with costs.

Apparently, Newshub executives met secretly with the heads of public broadcasters TVNZ and RNZ to propose exactly this about a week ago. This is revealed today by the Herald’s Shayne Currie, who reports: “The proposed news agency would have supplied stories, including video packages, to all three organisations – helping them reduce people costs. The agency would essentially have operated like the old NZPA newspaper model – a central hub providing coverage of ‘commodity’ style news. In other words, rather than the three organisations sending three separate teams to cover the same story or an event, one team would do it for all three companies and their platforms” – see: Newshub, TVNZ bosses’ secret discussions for joint news service one week before closure announcement (paywalled).

Currie says the idea didn’t get far: “Warner Bros Discovery’s New Zealand boss, Glen Kyne, met with TVNZ chief executive Jodi O’Donnell, chairman Alastair Carruthers and RNZ chief executive Paul Thompson on February 21, to discuss the plan for a joint news service between the three organisations. But despite its own financial issues, TVNZ’s board is understood to have rejected the idea at an extraordinary general meeting the following day.”

Other media in financial trouble

TVNZ is also in a very difficult financial situation. Today the broadcaster reported its latest big loss – see 1News’ TVNZ announces half-year loss as media companies struggle.

There’s been plenty of speculation about other media outlets being in financial trouble, or about to make some controversial restructuring. Stuff has recently separated its traditional Stuff.co.nz website operations from that of its mastheads (the Post, the Press, etc), leading to the obvious speculation that some of this is to be broken up for sale. There’s even been talk of the Spinoff wanting to buy parts of Stuff.

But Stuff’s owner and publisher Sinead Boucher – who recently told a parliamentary select committee that businesses like hers are “clinging on by their fingertips” to keep operating – has reacted strongly to deny growing rumours, protesting that “Stuff is a profitable, debt-free, standalone, independent media business.”

Responding to this today, the Herald’s media insider Shayne Currie points out that Stuff “refuses to release any financial details” nor answer questions about why other financial institutions have become involved: “Interestingly, the Public Trust holds a security interest over Stuff’s assets, as per a financing statement dated November 30, 2023. The BNZ also registered a security interest in early November.”

What should the government do?

There is now huge pressure on the government and Broadcasting Minister Melissa Lee, to help the media sector to survive.

Part of this could involve some sort of revived Public Interest Journalism Fund. This is being advocated for today by University of Otago media studies lecturer Olivier Jutel. He is reported as believing the controversial fund “could be a model for how a competitive pool of funding could be used to support independent operators” – see Susan Edmunds’ Would requiring a dividend fix the ‘uncompetitive’ TV market?

Alternatively, some are saying that government subsidies now need to be extended to the state’s current TV channels. Duncan Greive says: “the case for simply allocating large chunks of funding directly to TVNZ (for NZ on Air) and Whakaata Maori (for Te Mangai Paho) grows stronger. The downside of that approach is that it would represent a further swing toward the government favouring its own platforms over the private sector – something it is likely anxious to avoid.”

While there is clearly a case at the moment of market failure in the media sector, there will need to be very careful steps before the government decides to regulate or part with money for newsrooms. At least some sort of balance sheet needs to be established for how New Zealand has dealt with the media market since the 1980s, when neoliberal reforms established the basic policy settings in which NZ On Air would subsidise privately run media on a similar basis to public broadcasting, while requiring the main public broadcaster, TVNZ, to compete commercially with the private sector.

No other countries use this model, with most preferring a pure public broadcasting arrangement. Some argue that this model is why companies like Newshub haven’t been able to succeed – they have to compete with a state-backed TVNZ that doesn’t have to pay a dividend. And the state model has arguably disconnected the media outlets from their audiences and made them beholden to their funders, not the viewers.

Therefore, if the current model of state subsidies for public and private media is extended further, the whole problem could worsen. For more on this, see Kelly Dennett’s article in the Post: Is Newshub’s demise the canary in the coalmine? (paywalled).

In this, former Newshub CEO, Brent Impey cautions on putting more state money into this system: “Does the taxpayer want to put money into journalism? If they do, what are the expectations? Because if you get public money it’s absolutely critical the editors have editorial independence and are not seen as toe-ing the government’s line… I think the public quite rightly would question whether there were any strings to the funding.”

Regardless, the parties in power at the moment have come to see the current media as being overwhelmingly biased against their new government and in favour of the opposition parties. This might mean that the new government is rather disinclined to give the media even more money.

Media bias has become a huge issue. For some useful public polling on the question, in December David Farrar surveyed the public via this Curia market research company, asking the question: “Do you think the New Zealand media overall are biased towards the right, biased towards the left or not biased?” – see: NZ media bias (paywalled).

The overall results were interesting: 37 percent said the media was “Biased towards left” and 12 percent said the media was “Biased towards right”, with another 31 percent saying there was no bias, and 12 percent not sure. But perhaps more interesting, is to look at the political party preferences of respondents who didn’t believe there was any bias – only 18 percent of National voters thought there was no bias in the media. Similarly, it was 20 percent for Act voters. However, nearly half of all Labour and Green voters didn’t think media bias existed (49 percent and 46 percent, respectively).

Assuming that such polling also reflects what the new government thinks, then there will be a strong feeling that there’s a partisanship problem in the media at the moment, and any attempts to further save media outlets is just going to help the election of a Labour-led government in 2026.

Others will look at National refusing to bail out a failing sector and compare this to other industries that get special help. For example, left-wing commentator Gordon Campbell wrote about this yesterday: “Which industry is this government rushing to assist? PM Christopher Luxon says that Newshub can expect no government assistance to help prevent the closure of its entire news operation, because Newshub has to adapt to changing market conditions. Yet the tobacco industry? Different story. The Luxon administration is planning to cushion the decline of Big Tobacco by rushing its protection through parliament under urgency. To repeat: Newshub’s news operation is being left to sink or swim because that’s just market reality” – see: On the Newshub/Smokefree twin fiascos.

Similarly, writing for the Listener today, Greg Dixon says the government’s announcement that there’d be no bailout for Newshub “wasn’t a surprise. We all know that the only way for a giant multinational company to get a sweetheart deal from a New Zealand government to protect hundreds of jobs is to be a Hollywood studio or to have a smelter in Bluff” – see: Another kind of politics – a sad day for democracy (paywalled).

Growing distrust of the media

Somehow or another, public trust in the media needs to be recovered. Although this is a difficult topic for all concerned – there’s a reality that needs to be grappled with, that distrust is growing, and has played some part in the demise of some media outlets.

In this regard, Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters has had the most interesting things to say on Newshub’s demise. He’s been forthright about how Newshub’s closure would be a “disaster for this country’s democracy”. He’s also been quick to critique the state of the media landscape, explaining that outlets such as Newshub have declined in profitability partly because they have increasingly lost the trust of the public.

Peters is certainly correct that public trust in Newshub and other media has plummeted in recent years. According to the latest survey research by AUT’s Centre for Journalism Media and Democracy, trust in Newshub has dropped by 22 percent since 2020.

Furthermore, only 42 percent of New Zealanders say they trust the news media, and this has been steadily dropping – in 2020, it was 53 percent. This is much worse than for other countries New Zealand is normally compared to. What’s more, 69 percent of New Zealanders say they avoid the news – again, a much worse number than for other countries. Many New Zealanders now believe, according to the survey, that the news media is just an extension of the government.

The researchers say their latest research shows that the distrust is growing in 2024, and more people are moving away from some of the main news sources.

Winston Peters has published his critique of the New Zealand media landscape this morning on the Newstalk website, arguing media outlets have become too conformist and too ready to push the government line on key political issues. He says this clashes with the need of the “Fourth Estate” to be “impartial, politically neutral, fair and objective” – see: The state of New Zealand’s media (paywalled).

In his view, this is the reason outlets like Newshub have been losing their connection with audiences, as increasingly the media risks “becoming a sort of informal club, a coterie, a fraternity whose members find that their political agendas coincide”. He believes that a lot of the media outlets conspire to keep certain perspectives out of the public debate, narrowing down debate and disparaging those outside of the narrow consensus. He even cites a case, reported by RNZ, where news editors “discussed whether to report what I say about media bias – because what I’m saying is something they don’t agree with”.

The Deputy Prime Minister’s main beef is with the Public Interest Journalism Fund, a government subsidy for various media that is still in existence, but currently winding down. Peters says the $55m that was given to various private and public media outlets had “strings attached”, and this has fuelled public distrust in the media’s reporting, especially on topics such as Crown-Maori relations and Three Waters.

Here’s what Peters says is the key contentious condition that the government placed on recipients of the funding, which he says lacked any multi-partisan or public consensus: “It states that the media organisation must ‘actively promote the principles of partnership, participation and active protection under Te Tiriti o Waitangi acknowledging Maori as a Te Tiriti partner”. And have a ‘commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to Maori as a Te Tiriti partner’. If they didn’t sign up to this condition, they wouldn’t get the money. How can a politically neutral and independent media organisation give balanced political commentary, analysis and, in particular, ‘opinions’, when this is the basis for the funds they receive for their very survival?”

Peters says such funding had a direct impact on how the media covered key race relations issues, such as the Labour government’s own co-governance agenda, and was therefore “a recipe for bias and corruption”.

None of what Peters says here is uncontested. But as with all the aspects of the current ‘media apocalypse’, we now need to discuss such criticism within a big debate about the future of journalism and broadcasting, but also the pernicious and connected role that public relations play in dominating the public sphere.

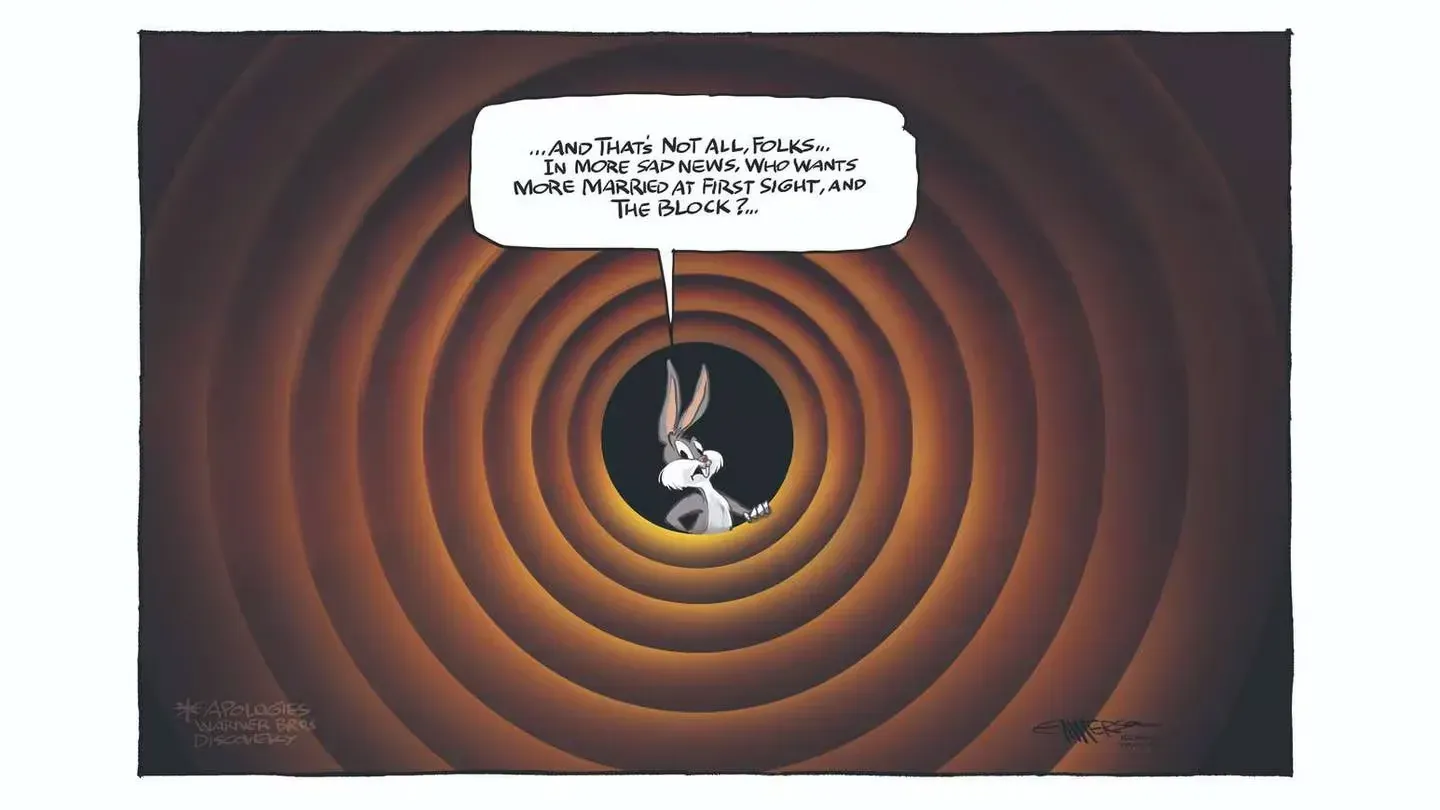

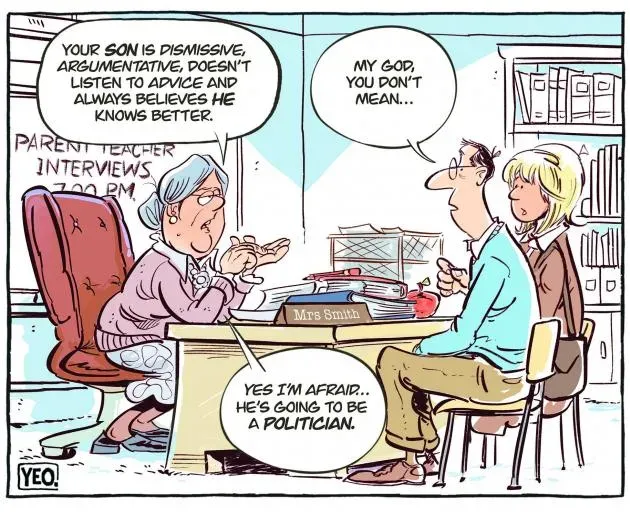

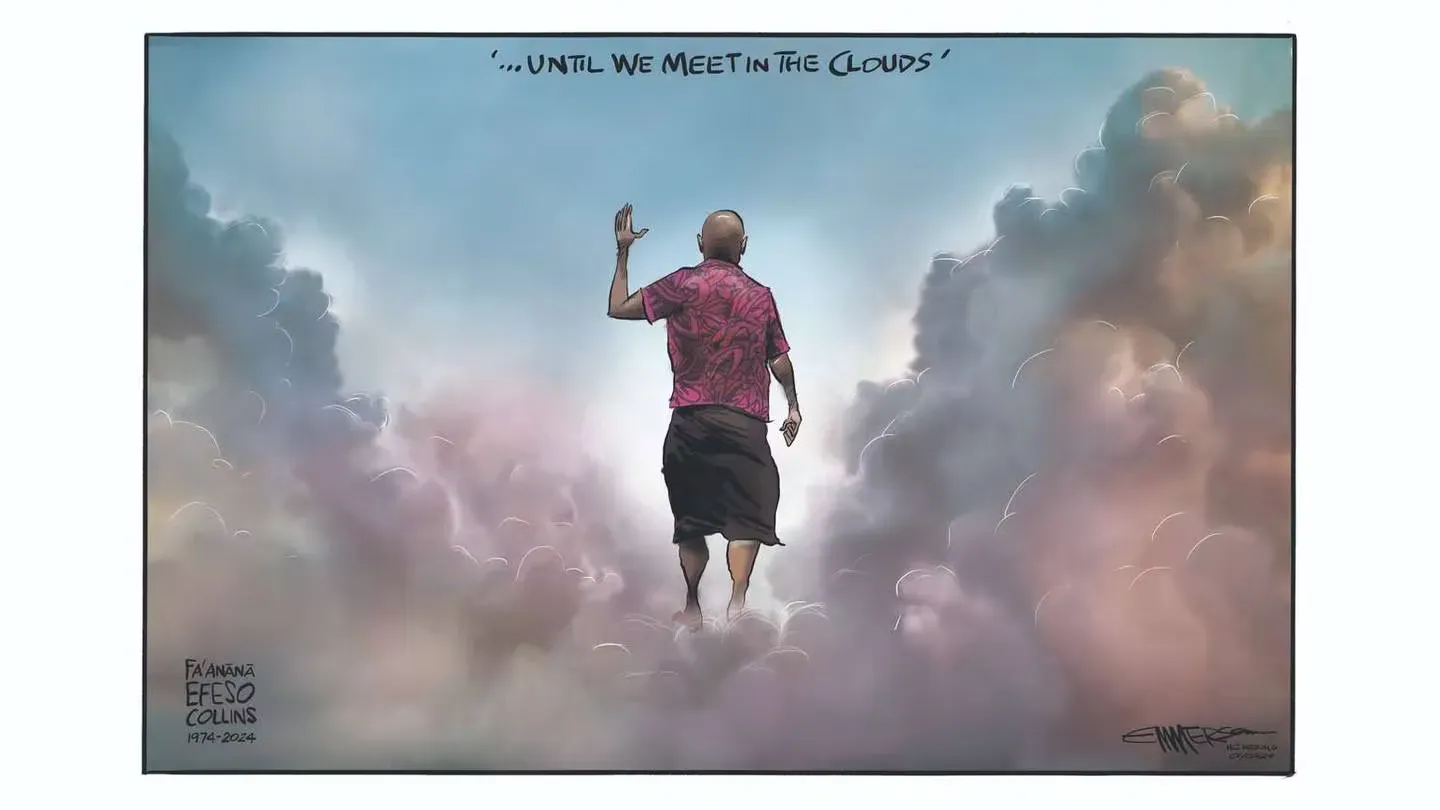

Cartoons today