Table of Contents

History, it is said, is written by the victors. But which victors, of which war? The United States lost the Vietnam War militarily, for instance: but the American left emerged victorious on the home front.

And they wrote a history which was every bit as false as the Soviets who pinned the Katyn Forest massacre on the Nazis.

In the “official” history of Vietnam-in-America, the War was always unpopular and it was placard-waving students and liberal elites who led the charge of righteousness against it. But that’s a lie: in fact, a majority of college students supported the War until at least 1969 and Nixon. Opposition was led by older, blue-collar Americans: the ones whose sons were actually fighting and dying in Vietnam, unlike draft-deferred, middle-class college kids.

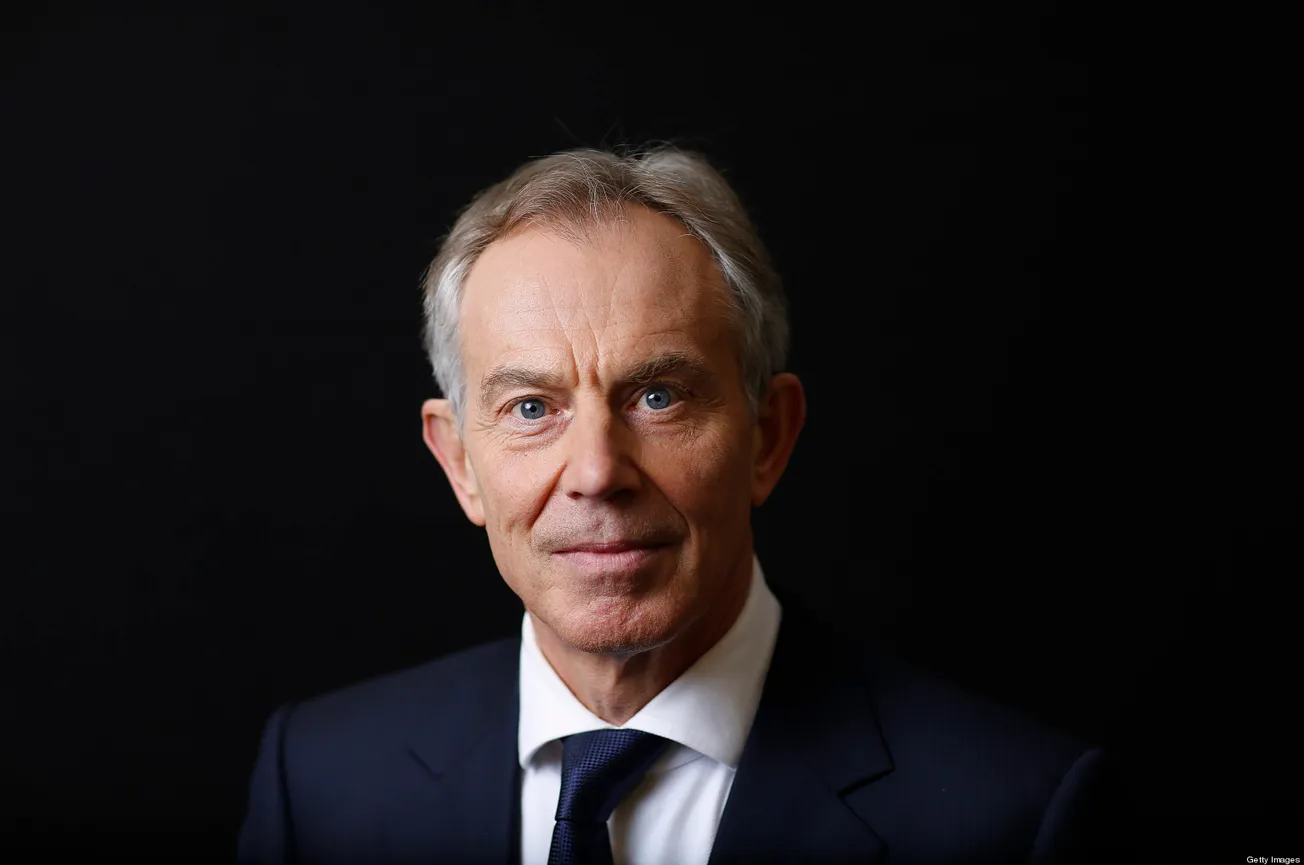

As we look back on 20 years of the War on Terror, a historian tries to demolish what he claims is another myth: “Blair’s War”.

In folk memory, it has become ‘Blair’s War’, driven by his delusions, his bad faith and his close alignment with a US president. But it was not just Blair’s War. It was Britain’s. The will to war was wider than many like to recall.

In fact, public opinion was strongly against Britain’s involvement. As pre-war polling shows, while there was a small but significant shift in favour, nearly two-thirds of Britons remained opposed.

But context is everything. Firstly, the British were opposed only insofar as they didn’t believe the claims of Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction. Should “UN inspectors find proof that Iraq is trying to hide weapons of mass destruction, and the UN security council votes in favour of military action”, then Britons were ready to turn on a dime: three-quarters would have supported war in that case.

Secondly, while unprecedented numbers of ordinary Britons marched in protest against the war, the elites were a lot more favourable.

Critics recall a silver-tongued premier hoodwinking the public, falsifying evidence, grovelling to a superpower, foisting a disastrous military expedition onto the British people and destroying trust in the state. The lamentations that accompanied the publication of the ‘Chilcot’ Inquiry report are highly personalised. They frame the historical error as one man’s doing.

Certainly, Tony Blair might have thought he could do what Margaret Thatcher had done with the Falklands war: save a flagging prime ministership. Obviously, that didn’t pan out as he intended. But he had plenty more cheerleaders than like to admit it now.

The ‘dodgy dossier’ had the willing hand of intelligence officials, who were convinced the WMD programme was real. Though Blair’s introduction to it had unwarranted certitude, the error of leaning too heavily on ambiguous evidence was not his alone. Even sceptics in the Foreign Office and Ministry of Defence were nourished on an optimistic account of influence.

Much as he is demonised by the left, at least Rupert Murdoch is up-front: he admits that he tried to influence public opinion in favour of the war, but concedes that the public simply didn’t go along with him (which should demolish, once and for all, the leftist fantasies of the Murdoch puppet-master pulling the strings of an unthinking herd).

Within the commentariat the cause of regime change straddled Left and Right, ranging across the ideological spectrum from Paul Johnson, Melanie Phillips and Anne Leslie to David Aaronovitch, John Lloyd and Nick Cohen. Defeat would prove an orphan. The Economist that later judged it ‘obvious’ that occupying Iraq made international terrorism worse, which reported the ‘damning’ conclusion that an adapted strategy of inspections and containment could have succeeded, is the same journal that, in February 2003, called for Saddam to be disarmed by force if necessary.

Blair also had the support of the political class. For the first time since 1950, the decision to go to war was debated by Parliament. Blair was not at all confident: he had his resignation papers ready if he lost. As it happened, the majority of MPs backed the decision.

These days, they’re not so eager to remember that.

Those who would make this issue an indictment of Blair will claim that his cabal misled others of good faith into supporting hostilities. This has been the retort of columnists such as Matthew Parris (‘we believed what we were told’).

History Today

This collective failure of memory isn’t just for politicians and pundits. While the polls quoted above showed clear opposition to the war, others were not so clear. YouGov polling at the time found that just over half of Britons supported the war.

Their memories are playing convenient tricks on them now.

Follow-up YouGov polling, 12 years later, asked Britons how they felt about the war in 2003. Only 37% admitted to supporting it, back then. In other words, one-fifth of Britons are lying about it.

At least Tony Blair has had the guts to stand by his decision. I’m not inclined to say many positive things about Blair, but at least I’ll grant him that much integrity.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD