Table of Contents

New Zealand Doctors Speaking Out with Science

Written in conjunction with an NZTSOS colleague.

When the vaccine mandates came into force for Health and Education workers, employers could apply for ‘Significant Service Disruption’ (SSD) vaccine exemptions for staff who refused to take the ‘vaccine’. These exemptions were meant to be for a short duration to provide the health service or school with sufficient time to make alternative employment arrangements in situations where losing staff would cause significant disruption to their service.

Recent OIA requests have revealed that these Significant Service Disruption (SSD) exemptions were granted for a very large number of healthcare workers – 11,005 in total.

In light of this newly released information, it is pertinent to examine the evidence that the Crown presented on SSD exemptions in the NZDSOS/NZTSOS case.

This hearing took place in the Wellington High Court between 3–7 Mar 2022 and challenged the Crown on the legality of the vaccine mandate. To support their case, the Crown submitted an affidavit by Rachel Mackay, who was group manager, operations, National Immunisation Programme. This affidavit was affirmed on 11 Feb 2022.

In her affidavit Mackay stated:

“As at 26 January 2021 [sic], we had received 450 applications for significant service disruption exemptions. Eleven applications had been granted, 1 was returned from the Minister with a request for further information, 235 applications were declined, and 1 application that was before the Minister was not proceeded with. Thirty-one applications have been assessed by the Panel and are awaiting a final decision; nine applications were withdrawn after Panel assessment; and four were returned as incomplete after Panel assessment. 158 applications were returned as incomplete from the triage process.”

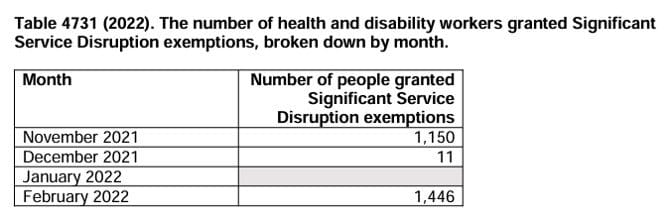

The information in this affidavit (that by 26 January only 11 SSD applications had been granted) appears to be at odds with information supplied by the Minster for Covid Response, Chris Hipkins, in response to a written parliamentary question from Chris Bishop on 2 Mar 2022 concerning the number of SSD exemptions. In his answer Hipkins produced a table detailing the number of SSD exemptions that had been granted by month and a footnote.

Please note:

– The exemptions included in the above table were each granted for a maximum of four weeks.

So, by 26 January (the date Mackay gives for the numbers in her affidavit), a total of 1,161 people had in fact been granted an SSD exemption, and by the time of the NZDSOS/NZTSOS hearing in the High Court, an additional 1,446 health and disability workers had been granted an exemption, making a total of 2,607.

The only way to reconcile these numbers with the 11 in Mackay’s affidavit is to realise that Mackay carefully and repeatedly refers to the number of ‘applications’ for SSD exemptions, not the number of workers who had been granted SSD exemptions. It is likely that everyone, judges included, have wrongly concluded when reading Mackay’s affidavit that one application related to one worker.

This was a reasonable assumption, especially considering that when referring to the SSD exemptions previously in her affidavit, Mackay had stated:

“That process requires the Minister to take into account the potential for supply chain disruption if the particular unvaccinated person cannot carry out the work …” (Paragraph 6, emphasis added)

“Under clause 12A, a PCBU can apply to the Minister in writing for a person specified in the application for an exemption from any provision of the Order. The organisation applies on behalf of the affected worker, and must specify the affected worker and their role. But the exemption is for the specific worker, rather than the PCBU.” (Paragraph 29, emphasis added)

“Significant service disruption exemptions are specific to the exempted person’s work and do not transfer to their vaccine pass required under the Covid-19 Protection Framework.” (Paragraph 31, emphasis added)

Additionally, Mackay had used the same ‘application’ terminology earlier in her affidavit when discussing the ‘Medical Exemptions’, where an ‘application’ clearly related to just one individual. The High Court was never given so much as a hint that an ‘application’ for a SSD exemption could cover a plurality of workers.

The assumption that one application covered one worker may have been reasonable, but it was wrong. Thanks to our OIA requests, we now know (and Mackay must surely have known this at the time) that an application for an SSD exemption could in fact cover many hundreds of workers! By the time the government mandates ended on 26 September 2022, only 103 SSD applications had been granted, yet this covered a total of 11,005 workers – an average of 107 workers per application!

This is confirmed by what Matt Hannant, Te Whatu Ora’s director of prevention, recently told Stuff:

“All 20 former DHBs applied at least once for an SSDE, with the largest single application covering 971 affected staff.”

This raises the important question. How can a situation be remedied where the Crown has produced a sworn affidavit to the Court that has contained misleading information that may have had a major impact on the outcome of a High Court hearing?

To make an assertion in an affidavit that is known to be false and is intended to mislead the Court, is an act of perjury, and under Section 109 of the Crimes Act 1961, is liable for imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years. Perjury, however, is usually reserved for lies of commission. In this case we may have a lie by omission.

The truth may have been told, but not the whole truth. What Mackay disclosed to the court was technically true, but by her omission the court was likely led to believe something that was completely untrue. A person in Mackay’s position had an ethical duty to disclose all material facts to the court. Her failure to do so is egregious and needs to be urgently addressed. Justice will not be seen to be done if the Crown is able to submit this without redress.

Would Justice Cooke have decided differently had he known that one ‘application’ could cover hundreds of workers, and that thousands of workers were being given SSD exemptions by the Crown at the same time as the Crown was terminating the careers of others? We do not know, but we do know that he had the right to be informed of this, and was not. Instead, he was likely led to believe that only a very small number of mandated workers (11 in total) had been granted SSD exemptions.

Additionally, this raises the question of what other ‘misinformation’ may have been presented in the Crown’s expert testimony. Under the High Court Rules, expert witnesses are not to advocate for the party that engages them, but have an “overriding duty to assist the court impartially”.

How Drs Bloomfield and Town, who were in the employ of the Crown and had been instrumental in advising the government in introducing the vaccine mandate, could then be accepted by the Court as ‘impartial assistants to the court’ on the justification for the mandate, raises significant questions. This is all the more so, when Bloomfield’s affidavit states, “I have relied on officials within the Ministry of Health to assist me in preparing this evidence.”

We know that many of the claims made by their expert witnesses (Drs Bloomfield and Town) were highly selective, strained the evidence, or were outright bogus[1]. The High Court, however, denied NZDSOS and NZTSOS the opportunity to cross-examine these ‘experts’, effectively removing the only tools that may have been able to expose these glaring biases and errors.

Further, there is the burning question of just how many health workers were given an SSD exemption for the duration of the mandate, or after declining the mandated booster. Hipkins told Chris Bishop in response to his Parliamentary Question, that the exemptions were granted for a maximum of four weeks.

This is flatly contradicted in information that has been released under the OIA, and we also know, thanks to Matt Hannant’s response to Stuff, “It was also common for PCBUs to make multiple applications in sequence, so affected workers were often listed in multiple applications.” This likely means that although an application may have only been granted for a four-week or eight-week period[2], it was subsequently followed by another application for the same workers for the next couple of months.

The Labour government successfully obfuscated the answers to these questions. It is to be hoped that the new government will have a bit more desire to shed some light and provide some remedies.

[1] Examples include:

- claims being referenced to studies that make no such claim;

- claims being incorrectly referenced to studies that in fact made contradictory claims;

- data from a ‘study’ being presented as evidence without informing the court that the ‘study’ was not an observational study but a modelling simulation;

- the court being told that “There are no known risks to pregnant women from the vaccine”, without the court being informed that Medsafe’s Risk Management Plan listed ‘Use in pregnancy and while breast feeding’ as ‘Missing Information’.

[2] According to Stuff, “Te Whatu Ora says the SSDEs were temporary, the longest of them lasting eight weeks”.

The outcome of the April 2023 NZTSOS appeal is still awaited.

Read more on the NZDSOS/NZTSOS case at the following articles: