Table of Contents

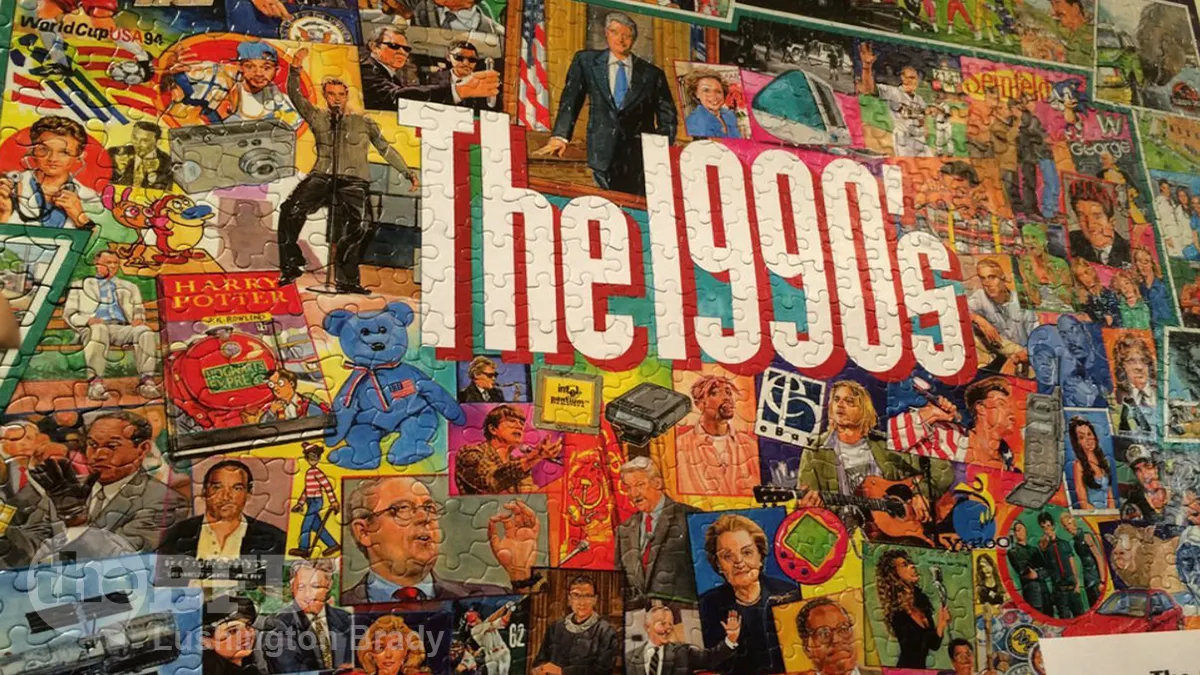

Did contemporary Western culture peak in the 90s? Nostalgia is a fickle beast and there is a strong tendency to valorise one’s 20s as the best of any era.

But I was in my 30s in the 90s. Much as I loved the 80s, there was a lot about it that sucked. For one thing, after a brief golden age in the early 80s, popular culture was awful. Garbage like Michael Jackson and Madonna, Masters of the Universe and Care Bears ruled supreme. All the good stuff was underground, and it’s hard to convey to today’s minds just how hard it was to access non-mainstream culture. For instance, though I was an early adopter of Goth stuff, many of the First Wave of Goth bands I read about, I never got to hear until the internet age.

The 90s gave us Nirvana and “the Year Punk Broke” into the mainstream, and The Simpsons (technically, 1989) and subversive, game-changing insanity of Ren and Stimpy.

More broadly, the 90s seemed to be the age when we struck the delicate balance between old-school homophobia and racism, and the demented degeneracy of “rainbow” ideology and the insane racism of “Critical Race Theory”.

It’s true that the 1990s weren’t perfect: there was a sprinkling of identity-based grievance and envy, but it was still safely contained in the universities. We genuinely thought experts knew what they were doing. There were also vital cultural vents, like TV comedy, and our playful pop scene thrived; now, it’s all bunged up. And we wonder why youngsters seem so barmy.

Certainly, the 1950s and 60s can lay claim to being an economic golden age. An almost unbelievable era when a single-wage, working-class family could afford a house, a car or two, modest annual holidays, and so much more. From 1971, as a myriad of graphs show, almost all economic indicators took a turn for the worst.

But I suspect that few of us would really want to live in the full sweep of the cultural milieu of that time.

Although, on the plus side, the older generation from pre-WWII were a source of generational wisdom who are sorely missed. It was even still possible in the 90s to meet veterans of WWI (I knew several).

What do I miss about the 90s? I miss the old folk back then. As Morrissey sings in his song ‘Oboe Concerto’, ‘the older generation have tried, sighed and died – which pushes me to their place in the queue’. Those older generations were often either fascinating or funny. The war didn’t seem so far off, and those who had lived through that period had a reassuring formality. They knew some of the things, like gratitude, duty, responsibility, in their bones; too many of us have now forgotten these things.

I vividly remember, as a child, being reminded to stand for old people and pregnant women, indeed women in general, on the bus. Dad saying grace around the table. Going to Sunday School. We’ve done our best to pass these lessons to our own children (successfully, if the praising comments of restaurant staff, when they were small, is any guide). Unfortunately, it too often seems that we were the exceptions rather than the rule.

Even for those of us inclined to rebel, which I duly did as a proper GenX punk, we did so from a secure foundation.

I can’t tell you how much fun it was to rebel then, anchored in the knowledge that there was the safety net of a secure society. Back in the 90s, we had a general, unspoken expectation and understanding that however mad things got, they couldn’t and wouldn’t get too mad. Bad things were usually noticed and stopped. In our present era – child sex changes, Jews frightened to walk the streets of London – that seems totally lost.

The Ramones, Sid Vicious, and even Nick Cave, may have played with swastika iconography, but they did so only out of a childish inclination to shock. There was no actual inclination to Nazi ideology. Today, we see the very people who call everyone “Nazis” re-enacting the atrocities of the Brownshirts in our streets, daily.

I’m not alone in my nostalgia. A recent YouGov poll has revealed that ‘Britons tend to think that several recent decades were better than the current era, particularly the 1990s and 2000s, of which 57 per cent and 60 per cent respectively say life was better. Another 51 per cent say the same for the 2010s, and a plurality also say so of the 1980s’.

The polling finds a strong correlation between the age of the respondents and the rose-tinted decade of the past they prefer.

In Woody Allen’s wonderful film, Midnight In Paris, a modern pines for 1920s Paris. Then, every night at midnight, he is magically transported back to the time when Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Picasso, Dali and Stein caroused in the cafes. In their turn, though, the Jazz Age bon vivants pine for La Belle Epoque of the late 19th century. Yet, when the protagonist is transported to that era, he finds Toulouse-Lautrec, Gaugin and Degas all wistfully dreaming of the Renaissance.

Again, perhaps this is inevitable. Time and again when reading writing from the tumultuous first half of the twentieth century in Britain, in Noel Coward’s Cavalcade or R.C. Sheriff’s Journey’s End for example, one encounters a wistful longing for the settled security of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. That was where their nostalgia took them back to – a period we now view as grimy industrial misery, filled with rampant sexism and class division and brutal colonial exploitation.

Spectator Australia

As Sam says, in The Lord of the Rings, “Things done and over and made into part of the great tales are different”. But will anyone ever look back on the 2020s with any real fondness?