Table of Contents

Once again, UK police are accused of dragging Britain into an Orwellian dystopia, with a viral video purporting to show two female police officers harassing a mother over her daughter’s alleged social media viewing.

While the exact facts of the case are confused, two things are so far clear: firstly, the available video is heavily edited; secondly, the official police version of events seems to be at the least untrue in some particulars. UK lawyer Daniel ShenSmith, who vlogs as Black Belt Barrister and is now acting pro bono for the family, has a pretty good summary of the case to date.

Such shenanigans will be familiar to New Zealanders, as well. There have been multiple instances of police ‘showing up for a chat’ at people’s houses, relating to social media posts. Some have escalated quite alarmingly.

With that in mind, the Good Oil has compiled a brief practical guide for New Zealand citizens as to their rights in such a situation (as per the Bill of Rights Act 1990, Search and Surveillance Act 2012 and relevant police procedures).

Bear in mind, of course, that this does not qualify as legal advice: when in doubt, consult a lawyer. Groups like the Free Speech Union can help you find a relevant lawyer.

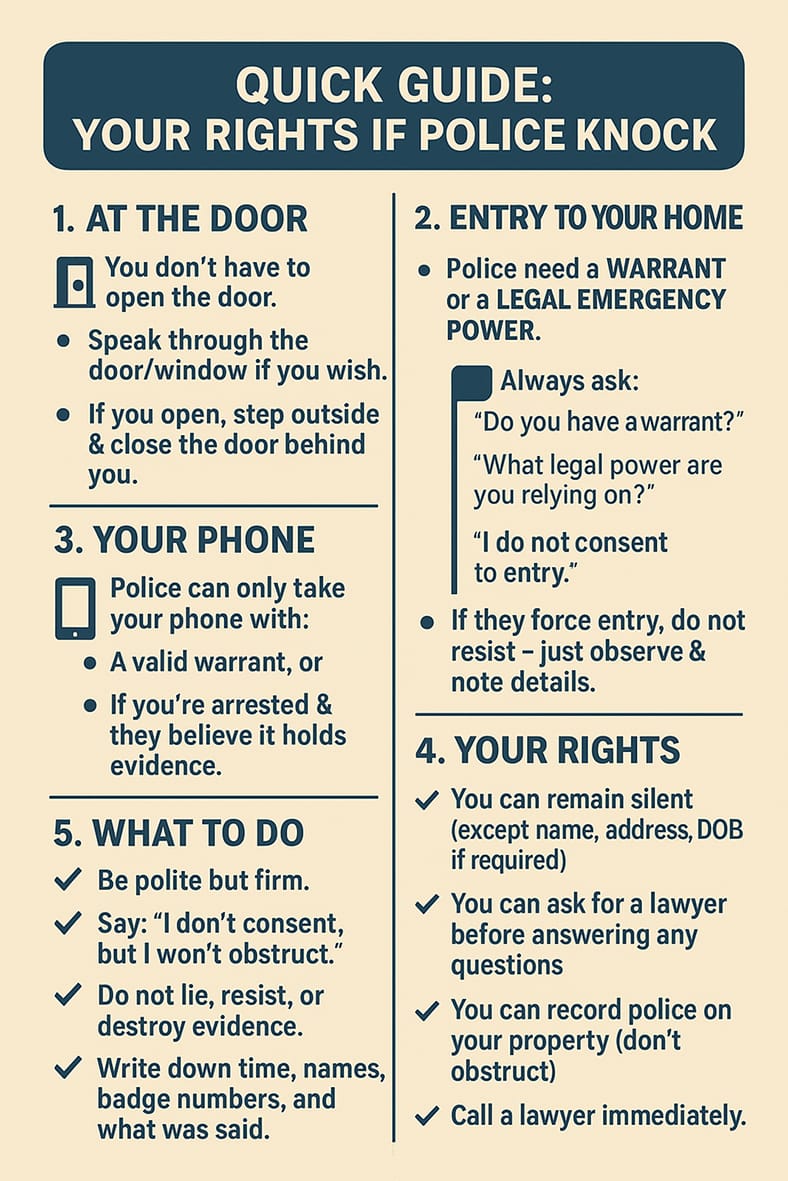

But most of us rarely have any interaction with police and certainly don’t expect them to knock on our door. Nor do we have much experience with lawyers, except for that long-ago conveyancing or maybe updating your will. So, use this handy guide as a reference. Download and print this card: stick it on the fridge.

The absolute cardinal rule, as with any interaction with police is:

Be polite. Stay calm.

Calm politeness will go a long way to not escalating a situation. After all, to be fair, pretty much every copper has to reckon with the possibility, however remote, that a knock on the door could be answered with a gunshot. You, the homeowner, are going to be pretty tense, too. Whatever you do, don’t make this fraught situation worse. That’s where knowing your rights helps: knowing your rights – and calmly asserting them – is the best way to protect yourself while avoiding unnecessary conflict.

Here’s what every New Zealander should understand if the police knock on their door, demand to be let in or attempt to take a mobile phone or other device.

1. General Right to Silence and Privacy

You do not have to answer the door unless police have a warrant or a lawful reason to enter (such as preventing harm or chasing someone).

You do not have to let police inside unless they show you a valid warrant or meet one of the limited exceptions.

You do not have to answer questions beyond providing your name, date of birth, and address if lawfully required.

You have the right to consult a lawyer under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990.

Remain polite, calm, and firm. Arguing or resisting physically can create further problems, even if you are in the right.

2. When Police Knock on the Door

Remember, police may knock on your door for many reasons: to ask questions, investigate a complaint or serve documents. When they do:

• You can choose not to open the door. You may speak through a locked door or a window. Even if you think this makes you look shifty, it’s still perfectly within your rights.

• If you do open the door, step outside and close the door behind you. This avoids giving ‘implied consent’ for them to step into your home.

3. If police asked to be let in

Police cannot simply enter your property without legal grounds. They need either:

• A search warrant issued by a judge, or

• Statutory authority without warrant, which can only be exercised under specific circumstances, such as to prevent serious harm or respond to an emergency, to arrest someone they believe is inside, or to prevent destruction of evidence in very limited situations.

So, you should:

• Ask to see the warrant. Police must show it to you if they have one. Read it carefully: it should state the address, date, what they can search for, and be signed by an issuing officer.

• If they don’t have a warrant, calmly state: ‘I do not consent to entry.’ This preserves your legal position even if police later enter anyway.

• If they force entry, do not resist. Simply state your objection (Say: ‘I don’t consent, but I won’t obstruct’) and observe what they do. Note the time, names, and badge numbers.

Which brings us to:

4. Recording the Interaction

You are absolutely allowed to film or record police at your own property, as long as you don’t obstruct them. In the UK incident, one of the police officers says she objects to being filmed and she has her bodycam. She has no legal right to object to being filmed, and as for the bodycam you or your lawyer are legally entitled to request the footage later. But, just in case, get your phone out and start filming: this is your legal right and a massive protection if police act wrongly. Keep a backup (cloud storage if possible).

As well as recording the interaction, write down everything immediately after: what police said, what documents they showed and what they seized.

5. If police try to seize your mobile phone

Phones carry private information, so the law gives you specific protections. Police can only seize your phone if:

• They have a valid search warrant that covers it, or

• They arrest you and believe your phone contains relevant evidence, or

• A warrantless search power applies (e.g., preventing evidence destruction).

Important!

You do not have to give them your password or PIN unless police have a relevant warrant. The Search and Surveillance Act does not give police automatic power to demand phone access.

If they seize your phone, ask for a receipt and a copy of the search warrant or grounds.

6. Additional advice to stay safe while protecting your rights

Do not lie to police – that can be an offence.

Do not destroy evidence or hide items, as this may lead to charges.

Do not overshare. Don’t volunteer any more information than you are legally required to, that being your name, address and date of birth. Remember, police can and will use anything you say against you. Aside from the minimum legally required information, you may remain silent. Again, don’t worry about looking shifty: it’s your legal right. You can ask for a lawyer before answering any further questions.

7. Legal Support

Always ask to speak to a lawyer before answering police questions beyond your basic identity. If you don’t have a lawyer, you can ask for a duty solicitor, available free 24/7 for initial advice. Community law centres, the New Zealand Law Society, or the Free Speech Union can provide further guidance.

Key Phrases to Remember

‘Do you have a warrant?’

‘I do not consent to entry.’

‘I want to speak to a lawyer before answering.’

‘I do not consent to my phone/tablet/etc being searched.’

As a New Zealand citizen, you have strong legal rights to privacy, silence and legal advice. Police cannot enter your home or take your phone without lawful authority. The safest approach is to remain calm, avoid confrontation, clearly state your lack of consent and seek immediate legal advice if police insist on entering or seizing property.

(British barrister Steven Barrett has a YouTube video discussing these issues. While his advice is UK specific, in general similar common-law principles apply in New Zealand.)