Table of Contents

No one living in America today has ever legally owned a slave. No one living in America today was ever legally a slave. No one alive in America today can remember slavery. Virtually no one in America today defends slavery.

There are many other countries who cannot say the same. But they not only cannot say, they will not say. Unlike the United States, which has never stopped facing up to what ended a century and a half ago, countries where slavery is a living memory refuse to officially admit to it.

Which countries? Here’s a hint: they’re not only not the United States, they’re not even the much-maligned Western countries.

Eight decades after slavery was abolished by imperial decree by Emperor Haile Selassie in 1942, this is how the memory of slavery is preserved in Ethiopia: as fragments passed down by grandparents […]

Zerfe Argaw is in her 50s, too young to have seen people being sold in the market, but she was told about the trade by older relatives. “I heard different stories,” she says. “Slave owners owned [entire] households as slaves and would sell whole families to buyers, including the children.”

There are no exhibits commemorating domestic slavery in the National Museum of Ethiopia. It is never taught in schools and rarely discussed in public.

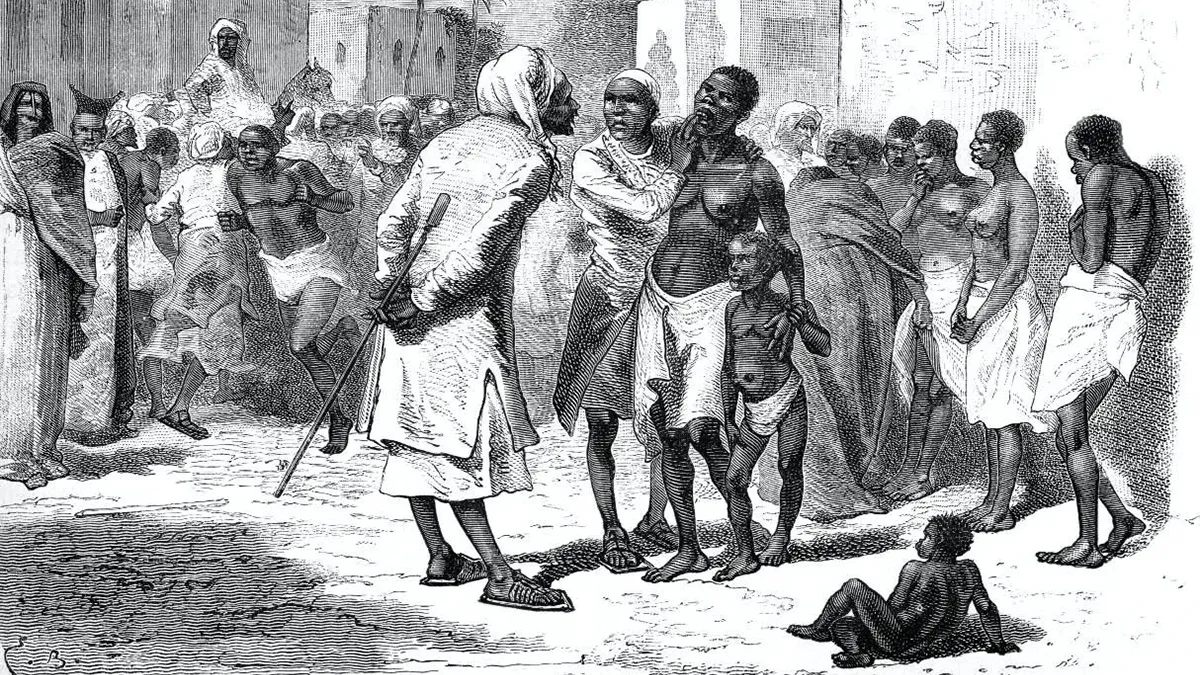

Yet slavery was once widespread in Ethiopia. Stretching back centuries, slaves served as soldiers, domestic servants and labourers, who were put to work at royal courts, in churches and fields.

Many were born into servitude. Others were captured in raids and during wars, or sold into slavery after they failed to pay debts. Much of the trade was domestic, although Ethiopian slaves were also sold across the Red Sea to Arabia and Turkey, where they were prized as concubines and servants.

Which is a reminder that many Muslim countries officially kept up the slave trade well into modern times. Mauritania didn’t make slavery illegal until the 1980s. When open slave markets resurfaced in the last few years, they were in Muslim Libya and Syria.

Slavery was also practised in African and Middle-Eastern countries on a scale that dwarfed the trans-Atlantic slave trade. That includes Ethiopia.

Ahmed Hassen, a professor of history at Addis Ababa University, says the number of enslaved people ebbed and flowed, especially during times of war, but estimates that up to one-third of Ethiopians were enslaved at different points in history.

In some districts, the proportion was likely even higher. The sociologist Remo Chiatti calculates that 50 to 80 per cent of people were slaves in parts of Wolaita, a southern kingdom centred on Dalbo that was absorbed into the Ethiopian empire in the 1890s.

“Slavery was everywhere,” says Ahmed. “It was the backbone of labour; it was the source of everything. It was not only landlords and the court of the emperor keeping slaves, but also rich peasants. If you had money, you had them.”

And they didn’t give them up willingly: Hailie Selassie only initially promised to end slavery as a condition of admittance to the League of Nations. Still, it continued well into WWII.

Even today, the visceral legacy of slavery permeates Ethiopia in a way that makes a mockery of the idiotic fantasies of Critical Race Theorists regarding the West.

Today, the impact of slavery is keenly felt. After abolition, many slaves became part of the families of their former masters, but in some areas the descendants of enslaved people are seen as impure and are marginalised, barred from participating in ceremonies such as funerals or marrying into other clans. In Addis Ababa, it is common to hear light-skinned highlanders refer to darker-skinned people from southern Ethiopia as “bariya” (slave).

Just as many Muslims today deride blacks as “abed”, Arabic for “slave”.

“Slavery in Ethiopia is not a historical phenomenon,” says an Ethiopian researcher, who did not want to be named. “Its legacy still affects people’s lives today.”

A teacher in Addis Ababa, who also did not want to be named, recalls a conversation with his mother. “She’s the type of person who, if she saw someone hungry on the street, she would bring them to our house to eat with us,” he says. “But when I asked her if I could ever marry someone from slave descent, she said, ‘No’. For her, it’s like a curse.”

The Guardian

On the whole, though, Ethiopia’s slaving past is a barely whispered secret. A former government commission into past injustices, including slavery, was never published. Generations of Ethiopians are growing up with “zero knowledge” that slavery was once so widespread.

Which all serves to put the ignorant idiocy of nonsense like The 1619 Project into much-needed perspective.