Table of Contents

Michael Bassett

The Mainstream Media, and especially the New Zealand Herald, regularly carry misinformed columns on the causes of the country’s low-grade economic performance over recent years. One old codger, John Gascoigne, who describes himself as “a Cambridge-based economic commentator” (not the university, alas!) correctly told us early this week that New Zealand was in a mess. And that things could be better. But in this one, as in all his previous columns, he reveals personal confusion. He has a fixation about the year 1984 when, he says, everything started going wrong. It was then that government policy turned towards deregulation, privatisation, downsizing, free trade etc, and the country, in his view, started going to hell in a handcart.

The thought that everything in the garden was rosy in the last years of Robert Muldoon is laughable to anyone with a good memory, or even a little knowledge of New Zealand’s economic history. By 1984 the First Labour Government’s huge additions to our welfare state were half a century old. Along with great improvements to health, welfare, education and living standards, those reforms, and additions to them during the 1950s, 60s and 70s, had given us a domestic inflation rate that constantly exceeded our trading partners’. This made it increasingly difficult to sell our produce in Britain and Europe. Official Economic Survey figures regularly told us that import controls, aimed at reducing excessive importing, were slowing New Zealand’s economic growth. By the late 1960s through a never-ending battery of controls, regulations, and subsidies, governments (mostly National) tried to keep the full-employment welfare juggernaut on the road.

Sheep numbers rose rapidly as resistance to our exports built up in Europe. Muldoon introduced the Sheep Retention Scheme that Prime Minister Norman Kirk labelled “the family benefit for sheep”. Their numbers skyrocketed to 70 million. Farmers were allowed to count their own! A farmer colleague of mine called it “the skinny sheep policy”; they were so skinny you couldn’t see them! With every control or subsidy came a tax fiddle of some kind. In desperation, through his Think Big policy, Muldoon sought to use the newly-discovered Taranaki gas fields to break the country’s dependence on high-priced imported oil. More than seven billion dollars were borrowed to finance an array of energy schemes, only to see the international price of oil slide steadily, undermining the new schemes’ economic viability. By 1984 we had a draconian wage-price freeze in force as well and were facing a record domestic deficit. Muldoon endeavoured to shoulder his crumbling edifice through an election, rebuffing advice from his officials to devalue the New Zealand dollar. On the afternoon following his defeat, Muldoon was informed by the Governor of the Reserve Bank that the foreign exchange market was closed until the then ministerially-determined value of the dollar was re-assessed. The thought that this is Gascoigne’s ideal world that Roger Douglas then proceeded to ruin requires mirth-suppressing medicine.

Of course, not everything that followed went to plan. It took a couple of years longer than anticipated to rein in inflation. There have been eight Finance ministers since Douglas. While the essentials of Rogernomics like the floating dollar, GST, and the Reserve Bank Act have stood the test of time, most ministers of finance have tinkered with economic settings since the 1980s. That’s understandable; time moves on. But not all the more recent changes have been as successful as the reforms of the 1980s and early 1990s that our columnist abuses. An upturn in productivity was a key feature of the late 1980s and early 90s, and the return to economic growth in 1993 can be sheeted back in large part to the eventual victory over inflation. In 2004, New Zealand’s Treasury published a significant article entitled New Zealand’s Economic Growth: An Analysis of Performance and Policy. It stated that “economic growth…has improved since the early 1990s. Its average annual GDP per capita growth … has been higher than the growth rate for the total OECD. In the eleven years to 2002, New Zealand’s average annual per capita growth was around 2.25% compared with the OECD average of 1.75%”. Consequently, Helen Clark’s Minister of Finance, Michael Cullen, was able to run a stable economy, albeit with a few spending frolics, while creaming his surpluses off into the Cullen Fund. It aimed to keep the cost of superannuation affordable as our population aged.

The country started to lose its mojo under the popular John Key. Like Keith Holyoake in the 1960s, Key refused to take steps that might temporarily inconvenience voters. Having promised to lift our economic performance to the equal of Australia, he quickly shied away from the disciplines necessary to attain that goal that were put before him in 2010 by former Governor of the Reserve Bank Don Brash, the preceding leader of the National Party. With Bill English pulling the financial levers, Key trundled along, winning elections. But he won’t be remembered for any economic initiatives of note. Spending remained at a manageable level that kept inflation in check, while 2017 welfare numbers still matched pre-GFC levels. But productivity figures declined. The underclass, that Key initially promised to tackle, was as big a problem when he left office in 2016 as it had been in 2008.

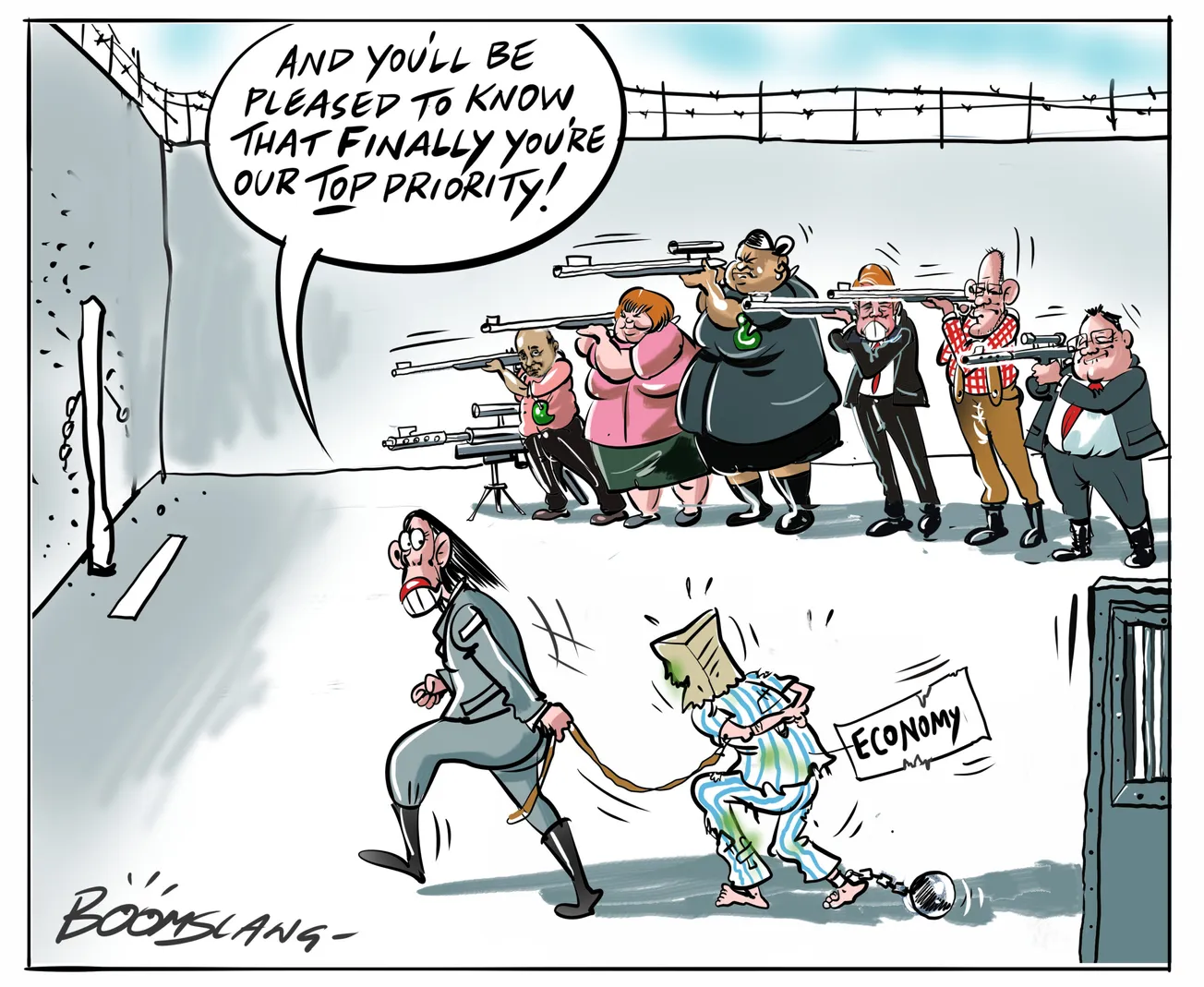

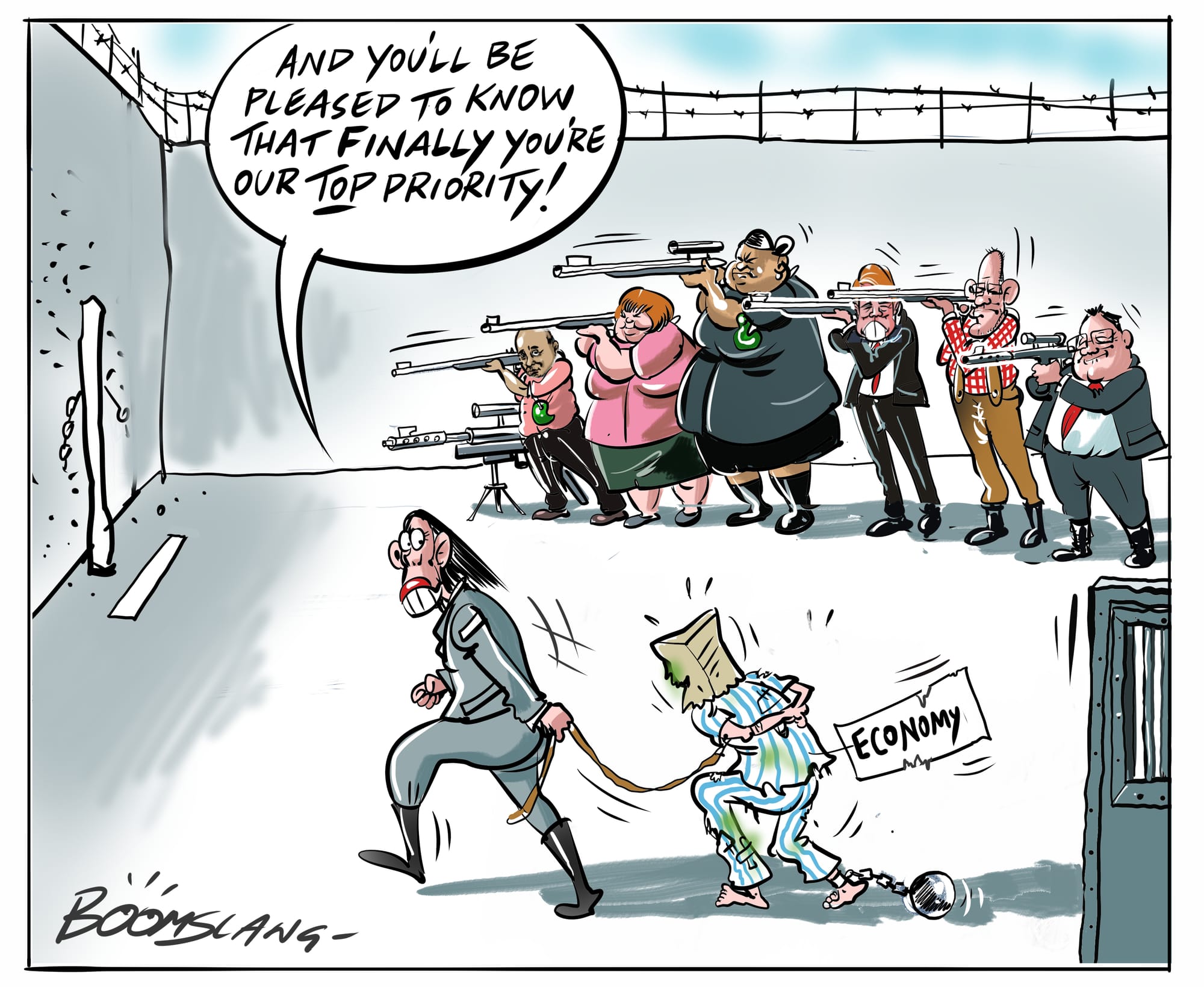

It was the arrival of Jacinda Ardern’s Labour government in 2017, courtesy of Winston Peters, that really put the skids under New Zealand’s economy. Full of fads and fancies, many of them in the welfare area that years of experience had shown were guaranteed to create more dependency, not less, Jacinda’s caucus of union hacks, Beehive apparatchiks and Maori agitators decided to spray money about. This was already well underway before Covid turned it into a force 5 hurricane. Grant Robertson was barely a teenager when inflation last ravaged the country and he’s been busy returning us to his youth. It’s worse still that the Herald can’t find more competent columnists with an understanding of economics like Bruce Cotterill, Steven Joyce, Richard Prebble and Liam Dann. The Mainstream Media in their search for more money from the Public Interest Journalism Fund, along with Radio New Zealand, are now working overtime to re-elect the worst government of our lifetimes. Expect more columns from our ill-informed Cambridge codger. And real Third-World status if they all succeed in October.