Table of Contents

R.J. Snell

mercatornet.com

R.J. Snell is Editor-in-Chief of Public Discourse and Director of Academic Programs at the Witherspoon Institute. Previously, he was for many years Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Philosophy Program at Eastern University and the Templeton Honors College, where he founded and directed the Agora Institute for Civic Virtue and the Common Good.

I’ve long engaged a group of close friends in political and theological discussions. As it happens, two of us agree on most topics and ally against the others. Mostly in banter, although not entirely so, we refer to ourselves as “Team Intelligence.” It’s friendly and jocular, even if somewhat ridiculous.

Who could be against intelligence? Who would wish to be dim-witted or slow; or worse, to be thought dim-witted and slow?

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle describes intelligence or understanding (nous) as the intellectual virtue by which we apprehend first principles. Such principles are known, but as first, they cannot themselves be demonstrated or based on other more fundamental premises. The intellect grasps them as true by an insight that is neither an intuition nor a conclusion. Thus, all other theoretical reasoning depends on intelligence, which provides fundamental principles.

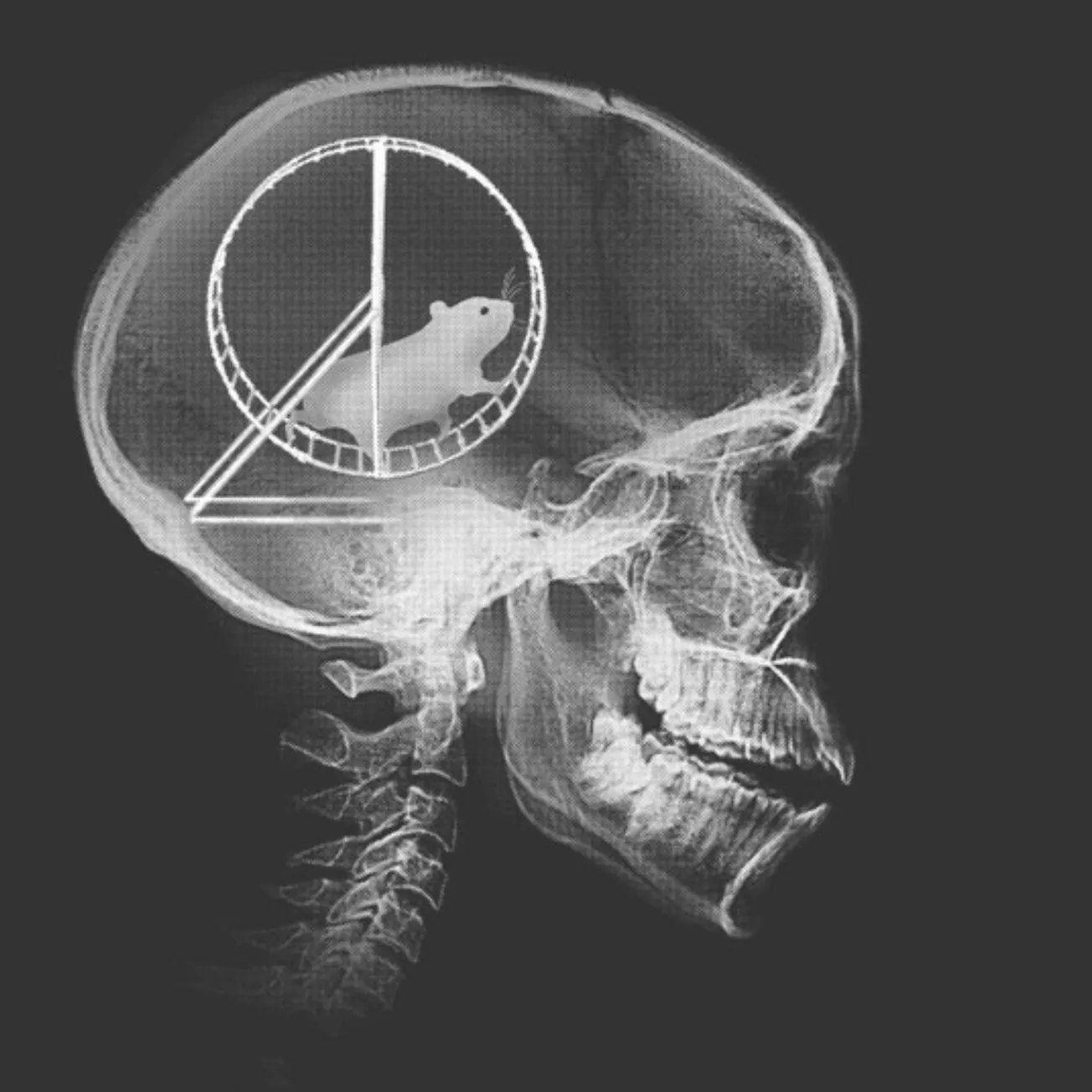

Nonetheless, it is obvious to any person of experience that intelligence is no guarantee of wisdom, morality, or even basic decency. The intelligent person may turn out worse than the dull precisely because he is clever and scheming. Just as one eventually concludes that interesting people are fine but solid and serious people make better friends, perhaps maturity requires moderating our admiration for the intellectuals, the clerks, and the clever types.

Stupidity’s varieties

Best known for his modernist classic, The Man Without Qualities, Robert Musil (1880–1942) gave a lecture in the anxious Vienna of 1937, “On Stupidity,” that is helpful here. The most “general notion of stupidity,” Musil suggests, is something like incapacity or inability. But at a time of “middle-class conventions,” the conception of stupidity is narrowed, confined to the domain of “mental work” and “rational achievements.” Stupidity is thus thought to describe “one who is ‘a little weak in the head.’” While a failure to understand may be the occasion of humour, Musil rightly notes there is nothing dishonourable in slowness. “Honorable stupidity is a little dull of comprehension, . . . is poor in ideas and words,” but also has “more than a little of life’s rosy cheeks” and is “charming.” Sam Gamgee comes to mind, or Bertie Wooster. They might need to count on their fingers, but there’s nothing dishonourable in doing so.

If honourable stupidity is a weakness of understanding, the dishonourable version “is by far the more dangerous.” It is not the absence of intelligence so much as “failure of intelligence.” Intelligence is present but out of balance and “misshapen and erratically active,” diseased in some manner. The “higher stupidity” is a “misculture” causing not dullness of mind but a kind of blindness or refusal to see.

Musil suggests three primary qualities of this kind of intelligent stupidity. First, it claims accomplishment and facility in matters beyond its competence. Second, it gives way to emotions at the expense of reason. Third, it is clever enough to invent rationalizations for its views, no matter how bizarre the view or silly the excuse. As a result, intelligence does not orient toward true knowledge of first principles and reality, as in Aristotle’s vision, but confuses the spirit. It results in a flight from reality, with all the cultural and spiritual pathologies attendant on living in an ersatz reality. Of course, given the unity of the human being, stupidity of this sort affects sensibility, causing taste and emotions to unmoor. Such intelligence becomes a dangerous disease of the mind and “endangers life itself.”

Culture of intelligence

Ours is certainly an age that privileges mental work, the creative class, the pundit, the intellectual, those of word and symbol; in short, ours is a culture of intelligence. The intelligent are valued, admitted, hired, promoted, and praised, and their product governs and directs us. But which sort of intelligence, honourable or dishonourable? Do our bright lights claim competence in what is clearly beyond the ability of policy and state? Are our best and most powerful governed by reason or emotions? Do our elites offer wild rationalizations for what is clearly bizarre? Do the most important institutions of our society harness and direct intelligence in service of reality or of misculture’s revolt?

Just now, the West comes across as dominated by enthusiasm. Our good institutions lack conviction, while the worst are frenzied with enthusiasm threatening our social order. The irrationality of our experts and their responses to COVID have wounded the education and well-being of our children, foisted a mental health crisis on us, fomented nihilistic violence, and destroyed wealth through inflation. An utterly destructive mania for human experimentation continues in the contagion of rapid onset gender dysphoria. We have no idea what puberty blockers will do long term, even as our cultural gatekeepers silence those asking the relevant questions. This is a plague of social disorder and chaos, much of it prompted by wild abstractions of the intelligent.

Roger Scruton suggested that many “grand liberal conceptions” about rights and freedoms are merely enthusiasms leaving “death and destruction in their wake.” For Scruton, conservative as he was, abstractions always have the whiff of higher stupidity about them, untethered from reality and invented as they are. Instead of cleverly constructed (and intelligent in their way) abstractions, Scruton suggested that “we rational beings need customs and institutions that are founded in something other than reason, if we are to use our reason to good effect.” This, he thought, is the “principal contribution that conservatism has made” to an understanding of human life, and an essential truth.

Seeking soundness

Given the confusion, the temptation among some on the right to respond to wrongheaded abstractions with abstract theories, projects, and grand schemes of their own is understandable. However, this mimics the “higher stupidity” responsible for fragmenting the institutions, structures, customs, and habits on which genuine reason depends, as Scruton has argued. Instead, we ought to value soundness far more than we do. We have become so accustomed to praising mental work, in Musil’s phrase, that we scout for smarts, recruiting and promoting and praising the bright kid while overlooking the solid youngster. Surely a person of good judgment, stolid character, and immovable rectitude is every bit as praiseworthy as the inventive and the quick—and in political and social life far more important.

The sound person is invariably a person of custom, of deference to the collected judgment of long experience, including experience of those long dead. They, after all, knew something and still exert judgment in the manners, mores, and habits of a people. The sound youngster possesses a sort of connatural knowledge of what is to be done, and so maintains stability, which is a basic condition for rational self-governance. Revolution and disruption—so cherished by the intelligent with their plans and projects—demand fluidity, liquidity, and suppleness, all skills of the highly intelligent, and all generally destructive of order and decent society. The disruptors of Silicon Valley flourish as San Francisco collapses, for example.

The sound person holds in trust the accomplishments of a civilization. It is no accident that Plato’s vision of education begins not with philosophy and the clever, but with formation of good judgment and taste. Eventually, the philosopher ought to rule, he suggests, but the ruler emerges from those already educated in good judgment; that is, the ruler must first be considered sound, a sensible person, so he doesn’t succumb to the novel (but nonsensical) proposal that ruins social order and well-being. He maintains a high regard for the guards of civilizational inheritance, the not utterly brilliant teacher who knows he has been asked to bequeath a cherished tradition to his pupils rather than tear it apart.

For most, having their customary way of life “problematized” results not in insight and clarity but confusion and vertigo. Far too many young people have had the rug yanked out from under them by their intelligent teachers; unsurprisingly, the result is alienation, nihilism, anger, withdrawal, and helplessness. The “failure to launch” bedevilling so many, including fear of “adulting” and the rejection of growing up, marrying, and parenting, is worsened by the cleverest among us. We often rather lamely refer to this as the failure of the elites, but they have not failed so much as destroyed.

We’ve privileged intelligence far too much. Or, better, we’ve privileged an intelligence quite proper to the world of science—with its doubt and scepticism and experiment and theories—but that cannot understand the human things. Our attempts to force a perfectly good tool into another sphere have caused grave damage. Theoretical reason, so necessary and wonderful within its bounds, is worse than merely erroneous in social and political life. It becomes stupid, highly so. Consider the vicious abstractions harming so many of the most vulnerable and dependent among us—gender ideology and political utopianism, for just two examples.

Aristotle knew better. Different orders of reality require different orders of intellect proper to them, and what he terms the well-schooled man—the sound person—knows the difference. The practical wisdom of the sound person is intelligence of the proper sort, an intelligence about acting. The person educated in this way “knows first principles,” and, indeed, the sound person lives in accordance with “intelligence and right order,” in his phrasing.

Soundness is intelligence apprehending the principles governing action. Such principles are universal, governing all human acts. But they are not theoretical, and it is not the clever but the good who most easily apprehend them.

We have great need for sound men and women, and until we value and praise them as we esteem the clever, and until the sound govern and give law to the clever, we will experience no end of our troubles.

This essay has been republished with permission from Public Discourse.