Table of Contents

Carlos Carrillo-Tudela

Alex Clymo

David Zentler-Munro

University of Essex

Carlos Carrillo-Tudela is a Professor of Economics at the University of Essex, UK. He is also a co-editor of Labour Economics, The Official Journal of the European Association of Labour Economists (EALE).

Alex Clymo is an Assistant Professor at the Economics department of the University of Essex. His research focuses on macroeconomics, labour markets, and unemployment.

David’s research interests include labour markets, wage inequality, wealth inequality and policies related to these topics.

The UK economy has a problem with its over 50s: following the COVID pandemic, they have been leaving the labour force en masse, causing headaches for businesses and the government. Roughly 300,000 more workers aged between 50 and 65 are now “economically inactive” than before the pandemic, leading a tabloid paper to dub the problem the “silver exodus”.

Being economically inactive means that these older workers are neither employed nor looking for a job. Of course, it could simply be that workers saved more during the pandemic and can now afford to retire in comfort earlier than planned.

But if older workers have been put off work due to health risks or lack of opportunities, it would mean the economy is being deprived of potentially productive workers – which could cost the state in various ways. So what’s going on?

Making sense of the exodus

In our latest research, which has just been made available online as a policy briefing note, we have taken the deepest dive yet into rising economic inactivity among the over-50s and what it means for the economy using the most recent UK Labour Force Survey (LFS) data.

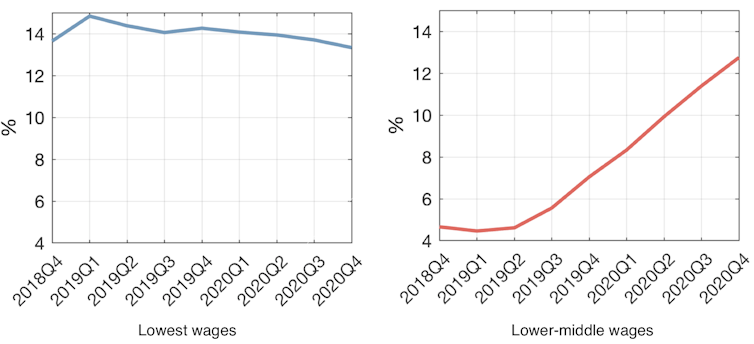

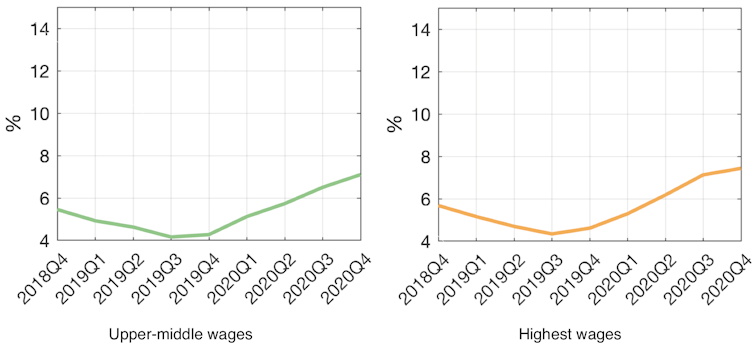

Surprisingly, the silver exodus is not concentrated in the richest segments of society – even though one might expect that they would be the most able to retire. Instead, it is mainly a middle to lower-middle income phenomenon. As shown in the charts below, the largest rise in inactivity post-pandemic is coming from workers in the lower-middle income bracket (earning roughly £18,000 to £25,000 per year in their most recent job). In each chart, the line shows the percentage of employed workers aged 50-65 who became economically inactive one year later.

Workers beccmoing inactive (%) by income quartile

There is also other evidence to support the view that the increase in inactivity is concentrated in the lower-middle part of the income distribution. For example, there has been a larger rise in inactivity among people who rent, rather than own, their own homes, and among those in lower paid industries and occupations. There has also been a smaller rise in inactivity among highly educated workers.

What jobs are older workers leaving, and why?

The industries with the largest percentage rises in inactivity among the over-50s are wholesale and retail (40% rise), transport and storage (+30%), and manufacturing (+25%). Meanwhile, the occupations with the largest percentage rises are process plant and machine operatives (+50%) and sales and customer service occupations (+40%). To put this in context, the comparable percentage rise for over-50s for the whole economy is 12%.

Several factors potentially explain these differences. The sectors in question were in long-term decline before the pandemic, and they were also hit hard when COVID arrived. Workers might have considered it unlikely that they would get their job back in a declining sector, and may have chosen to retire rather than looking for another job or retraining.

These are also sectors with high levels of social contact where it’s not possible to work from home, so perhaps some older workers chose to resign out of fear for their health. Taken together, the message is that the increase in inactivity has been driven by older workers perceiving lower returns from continuing to work: why keep working in a low-paid job in a declining and pandemic-afflicted part of the economy?

Will they come back to work?

It is not uncommon for workers to become economically inactive following a recession, because finding a job is hard and people can become discouraged. This is what happened after the global financial crisis of 2007-09, for instance.

It could be that workers in today’s exodus will resume searching for a job when the economy improves, but there are no signs of this happening. The rise in inactivity among the over-50s is already three times higher than it ever was after the last financial crisis.

Several facts also suggest that these people really don’t ever want to come back to work. All of the rises in inactivity is coming from workers who say they don’t want a job and think they will “definitely” never work again. Their main reasons are retirement and sickness, although the data reveals that the rise in inactivity due to sickness started at least two years pre-pandemic and was not much affected by the pandemic itself. In other words, a desire to retire is really the main reason for the rise in inactivity.

It’s worth pointing out that before the pandemic, the number of retirees was falling as workers had been retiring later in life. This was driven by increases in the state pension age, which rose from 65 to 66 from 2019-20. The rise in retirements that we have seen during and after the pandemic is partly the emergence of an underlying trend that was hidden while the state pension age rose.

Implications and policy challenges

This unprecedented rise in inactivity among the over-50s poses significant challenges for the economy. It comes at a time when the government is having to deal with increasing resignations among other age groups, labour shortages, the rising cost of living, and the evolving effects of Brexit. Given their relatively low income, these retirees could also potentially face financial difficulties later in retirement and add pressure to government spending. What then can be done to halt or even reverse the silver exodus?

The rise in inactivity is not in the lowest-income parts of society, where the government concentrates its efforts to incentivise work through the benefits system. The government might therefore consider extending these incentives, such as Working Tax Credits, to reach lower-middle-class people to try and encourage them to return to work.

Perhaps the cost-of-living crisis will force the over-50s back into work, partially solving the UK’s labour shortages. But solving one problem with another is not likely to make anyone – workers, businesses or the government – any happier. Difficult days, therefore, lie ahead.

Carlos Carrillo-Tudela, Professor of Economics, University of Essex; Alex Clymo, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Essex, and David Zentler-Munro, Assistant Professor in Economics, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.